The Kids Are Alright With UFOs, Part 1

How a children's author foresaw the "contactee" experience of the 1950s

In 1952 the children’s magazine Jack and Jill published a fascinating example of precognition—or predictive programming—involving human contact with a UFO and its pilot.

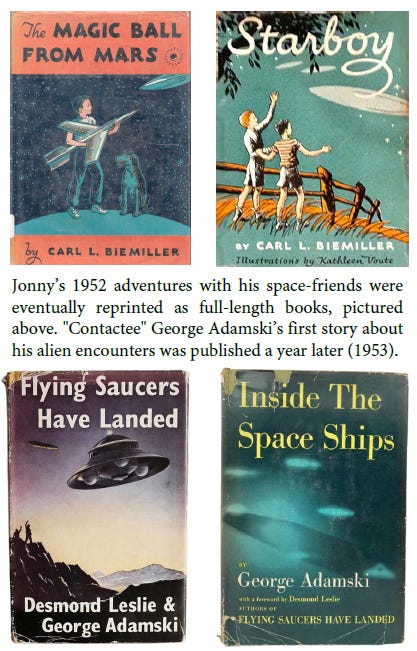

The November issue featured the first chapter of “Jonny and the Space-o-Tron”—a short sci-fi story by author Carl Biemiller about a New Jersey boy who witnesses the landing of a flying saucer and its occupant. While the plot may sound run-of-the-mill by today’s standards, “Space-o-Tron” and its sequel, “Jonny and the Boy From Space,” are important to the history of UFOlogy for an interesting reason. Both stories share a startling number of similarities with 1950s-era tales told by “contactees” like George Adamski and Truman Betherum—individuals who publicly claimed to interact with beings from space. However, Biemiller’s initial adventure involving Jonny’s run-in with a UFOnaut was published a year before any “contactee” literature appeared on bookstore shelves.

In a prescient coincidence, Biemiller’s story incorporated a host of concepts that became recognizable components of subsequent UFO reports. From clandestine government agencies, to theological musings by spacemen, the author’s pen was prophetic when it came to identifying future UFOlogical themes.

In the first installment of “Jonny and the Space-o-Tron,” we’re introduced to 8-year-old Jon Jenks—a normal 1950s youth living with his parents on a quiet farm in northern New Jersey. One summer evening, after listening to his parents discuss reports of flying saucers seen in the area, he wanders into a nearby pasture to catch a jarful of fireflies.

Within moments of arriving, Jonny hears the eerie call of an owl, followed by the whoosh of a large object overhead (many modern UFO accounts note the presence of owls during an ET experience—see the work of Mike Clelland).

The sound turns out to be a glowing airship with a humanoid driver. Biemiller’s description of the alien visitor shares a likeness with the “space-brothers” later portrayed by contactees like George Adamski.

Note the similarities between Biemiller’s cosmic companion, “Arkon,” and Adamski’s “Orthon” (even their names are alike):

The list goes on:

Jonny received a marble-sized ball of metal from Mars.

Adamski claimed he acquired a piece of space-metal discarded by a Venusian.3

Jonny was initially “frightened” by the visitor’s strange craft, but his fear quickly evaporated. He noted how odd and abrupt this transition felt, almost as if his emotions were being manipulated by an external force.4

Likewise, Adamski reported an unusual absence of fear the first time he met Orthon: “Suddenly, as though a veil was removed from my mind, the feeling of caution left me so completely … I continued walking toward him without the slightest fear.”5

In “Space-o-Tron,” the visitors often communicated telepathically.6

Similarly, contactees claimed to receive silent messages from otherworldly intelligences. Adamski tells us that Orthon conversed by transmitting “mental pictures” into his mind.7

Jonny’s alien admitted that space-people, “check up sometimes, to see that [we] don’t hurt [our]selves too much.” This directive is paradoxically paired with the rule that “nobody in a flying saucer is supposed to interfere with anything on your earth.”8

The same oxymoronic talking point was put forth years later by Adamski’s intergalactic emissaries who swore that they didn’t “actively interfere” with events on our planet.9 They later admitted that they “help[ed] and guid[ed] [us] as much as [we] would permit.”10 Adamski further muddied the waters by concluding that space-people were here to “help us and perhaps protect us from even ourselves.”11

Both ETs even give the same, tired lecture about the nature of mankind. When Arkon rescues Jonny from a group of kidnappers, he makes the child sit through a patronizing speech about humanity’s shortcomings:

“Poor little earth boy,” said the voice quietly, “here you are in the state so common to your people—having trouble …”

“Earth folk will not be ready for other environments until nice boys like you grow up to have still nicer boys who don’t have to hurt other people to get what they want.” The man’s voice was gentle. ‘‘Out There things like that don’t happen.” 12

His spiel sounds a lot like the opinions expressed by the space-people in contactee lore. Adamski’s benevolent Venusians were ostensibly motivated by messages of peace, love, and redemption for mankind. Dismayed by our constant acts of aggression, the visitors from space held out hope that one day humans would evolve and join the ranks of other cosmic “utopias” populating the universe; planets without “sickness or poverty … nor crime, as [we] know it.”13

It’s not surprising that Arkon’s and Orthon’s vehicles resemble one another—the “saucer” shape was a widely recognized UFO design at the time. Nevertheless, other commonalities between their vessels are worth pointing out. Both authors use the word “beautiful”14,15 to describe their respective craft. Jonny excitedly portrays Arkon’s ship as “a shape—blurred, then firm … so much a part of the air itself that it cast no shadow as it formed an almost-unseen umbrella over their heads.”16

This depiction brings to mind Orthon’s “translucent” UFO, which lacked any “definite form” as it traversed the skies.17

Both narratives also include the concept of a “mothership” capable of holding smaller recon vessels within. In Jonny’s story, the main ship releases “small space machines into [our] atmosphere.”18 In a similar fashion, Orthon’s craft dispersed “Scout Ships” that allowed for a closer inspection of Earth.19

Read Part 2 here.

Biemiller, Carl, “Jonny and the Boy From Space,” Jack and Jill, vol. 16, no. 6, 1954, p. 17.

Adamski, George, Flying Saucers Have Landed, The British Book Centre, 1954, p. 195.

Adamski, George, Inside the Space Ships, Neville Spearman Limited, 1966, p. 39.

Biemiller, Carl, “Jonny and the Space-o-Tron,” Jack and Jill, vol. 15, no. 1, 1952, p. 26.

Adamski, Flying Saucers Have Landed, p. 194.

Biemiller, “Space-o-Tron,” Jack and Jill, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 31.

Adamski, Flying Saucers Have Landed, p. 198.

Biemiller, “Space-o-Tron",” Jack and Jill, vol. 15, no. 5, p. 42.

Adamski, Inside the Space Ships, p. 124.

Ibid., 163.

Adamski, Flying Saucers Have Landed, p. 221.

Biemiller, “Space-o-Tron,” Jack and Jill, vol. 15, no. 5, p. 40.

Adamski, Inside the Space Ships, p. 165-166.

Ibid., p. 189

Biemiller, “Space-o-Tron,” Jack and Jill, vol. 15, no. 5, p. 40.

Biemiller, “Boy from Space,” Jack and Jill, vol. 16, no. 6, p. 17.

Adamski, Flying Saucers Have Landed, p. 206.

Biemiller, “Boy from Space,” Jack and Jill, vol. 16, no. 9, p. 24.

Adamski, Flying Saucers Have Landed, p. 185.