The Kids Are Alright With UFOs, Part 2

We conclude with more weird similarities between Adamski's space-brothers and a serialized children's novel

In Part 1 we examined the overlapping themes in Carl Biemiller’s 1952 short story, “Jonny and the Space-o-Tron,” and George Adamski’s contactee tales—which didn’t see publication until a year later.

In Part 2, we conclude our analysis and reveal additional motifs within Biemiller’s work that seem to predict many elements of contemporary UFO encounters.

Like many contactee reports of the 1950s era, religious overtones abound in both Biemiller’s and Adamski’s yarns.

In “Jonny and the Space-o-Tron,” the precocious Jonny probes the alien Arkon on the existence of “God”:

Jon had an amazing thought. There was another important question he should ask … “Could—could you just tell me one more thing?” he pleaded. “Do the people on your planet know everything about—about God?”

“No, Jonny Jenks, we don’t know everything about God. But He’s there—bigger than all the stars and systems of stars.”

Compare the previous exchange to Adamski’s dialogue with Orthon in his debut book (published a year later), Flying Saucers Have Landed (1953). The similarities are striking:

“Suddenly the thought came to me to ask if he believed in God? …

And he said, ‘yes.’ …

But he made me understand … that we on Earth really know very little about this Creator.”

Curiously, there’s also a layer of religious symbolism embedded in the name of Jonny’s aerial visitor, Arkon.

In Greek, arkhon means “ruler,” and Christian Gnostics believe that “archons” are evil, malevolent entities who control the earth and make trouble for humanity. According to Daniel McCoy of Gnosticism Explained, archons are “demonic beings who rule the world from the skies and try to keep the souls of humankind imprisoned in the world.” With all of this baggage, “Arkon” is an eyebrow-raising choice to name a character in a children’s story.

What’s more, Arkon’s ship is named “Unit Dekon.” Besides being one letter away from the word demon, the word dekon means “pastor.”

Beyond predicting the prototypical elements of a “contactee” interaction a year before the craze began in earnest, Biemiller touched on other UFOlogical motifs that would reemerge in UFO reports for decades.

Here are some additional parallels between Jonny’s literary adventures and the stories told by UFO witnesses and experiencers:

In “Space-o-Tron” a sinister black sedan à la the Men in Black follows closely behind the Jenks’ vehicle on several occasions.

They eventually run George off the road and kidnap Jonny.

The intelligence community and UFOs: After learning about his son’s close encounter, Jonny’s physicist father (whose name happens to be George … as in Adamski!) arranges a date with the ominous-sounding “Foundation”—a covert group of scientists located in Washington D.C. with ties to the intelligence community. On their way to talk to the Feds, Jonny’s dad reveals how important “a building called the Pentagon” is for his associates: “people from our Foundation visit there a lot.”

Oblivious to his son’s growing unease at the prospect of being interviewed by random spooks about his ET experience, Jonny’s father explains that “there are men in that building who are already interested” in the details of his encounter.

On the way back from D.C., the Jenks boys stay at a hotel where Jonny quaintly geeks-out over 1950s luxuries like air conditioning, cold tap water, and the free pad of hotel paper in their room. Mr. Jenks continues to allude to the clandestine nature of his work with the “Foundation,” advising Jonny not to tell his mom about the day’s events: “There are some things that we don’t talk about on telephones from hotel rooms.”

Jeez George! Paranoid much?

When he first appears, Arkon is vague and elusive with Jonny’s easy questions—an annoying trait that is often reported by those who converse with otherworldly beings.

When asked who he is, the spaceman simply states: “I’m a visitor, Jonny.”

When questioned about his reason for coming to Earth, the dodgy extra- terrestrial replies: “I guess you’d call it just looking around, Jonny. I came here on an experiment.”

Why can’t these space-people ever give us a straight answer?

We learn that the visitors might be interested in our nuclear weapons—another conventional trope in UFO mythology. In the scene where Jonny is being interrogated by G-men, they reveal that they’re involved in the development of the atomic bomb: “Folks around here call it the Atomic Energy Commission.”

“Atom bombs and things,” said Dad.

The man from “Out There” later hints that the reason they came to check up on Earth was because we “have atomic power now.”

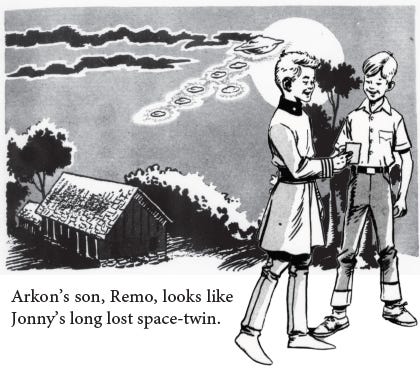

In Boy from Space, Arkon leaves his son with the Jenks family so that he might experience life as an Earth child. This is reminiscent of the accusations made about extra- terrestrial “Grays,” who allegedly abduct people that they then use as surrogate parents for alien-human hybrid babies. These tales echo even earlier myths dealing with fairies that were believed to steal human children and replace them with supernatural doppelgängers. Arkon’s “starboy” son even creepily looks like Jonny, giving off a distinct “changeling” vibe.

The story of Jonny and his space visitors may seem mundane by today’s standards, but considering when it was published, it presents itself as a curious predecessor to the stories told by contactees and UFO witnesses in subsequent decades. From Orfeo Angelucci to Truman Bethurum, a number of famous contactees claimed to have had their first close encounters the same year (1952) that Jack and Jill first released Jonny’s tale—but their accounts weren’t published or widely-known until at least a year later. Interestingly, Adamski claims his alien contact began in earnest in November of 1952—the exact month and year that “Jonny and the Space-o-Tron” debuted.

We aren’t suggesting that author Carl Biemiller is the originator of every UFOlogical trope that appears in his stories—many of these devices can be found scattered across earlier works of science fiction—but the sheer number of commonalities between Jonny’s adventure and those of later contactees is intriguing. Especially in relation to Adamski, whose tales would become known as the archetypal contactee experience of the decade.

Was Biemiller’s story simply the result of a random string of genre tropes? Or are its similarities with later close encounter reports attributable to more subtle mechanisms? A byproduct of the collective unconscious? Part of a predictive programming campaign to shape public perception about visitors from space? “Revelation of the Method” hidden in the pages of a child’s reader? Other speculative musings ending in a question mark?

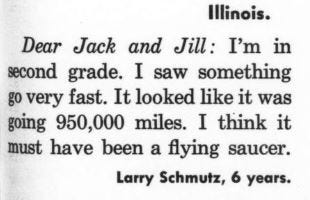

Whatever its inspiration, Jonny’s exploits left an impact on Jack and Jill’s young readers. Take it from 6-year-old Larry Schmutz, a subscriber from Illinois who was seeing saucers shortly after “Space-o-Tron” came out:

Don’t worry, Larry. Chances are, it’s being driven by a benevolent space-brother performing a routine welfare check of Earth.

Very interesting! Thanks for sharing. I'd be curious to know how Adamski came across the story. I don't believe he had any kids, but I think Leslie did. Or maybe he just dug kids lit.