Writing Off Saucers, Part 2

Part 1 here

Raymond A. Palmer took over editorial duties on the pulp sci-fi magazine Amazing Stories (AS) in 1938, well before UFO-mania infected popular media. His bosses at Ziff-Davis Publishing initially discouraged interest in the topic, but as the shiny aerial discs captivated the public in 1947, Palmer was given the green-light to offer up a different class of saucer-inspired sci-fi. So important was his contribution to the development of the phenomenon that ufologist John Keel nicknamed him “the man who invented Flying Saucers.”

Palmer curated a purposeful departure from John Campbell Jr.’s hard-science SF magazine, Astounding Science Fiction (ASF). Amazing featured stories with elements of fantasy and pseudoscience. Explaining his mindset, Palmer explained that he “admire[d] much about the policy of Astounding Science Fiction,” but felt its concentration on scientifically accurate fiction was “too specialized.” His version of SF would include ancient mysteries, aspects of mysticism, and other occult themes.

Curiously, a few stories about saucer-shaped craft from other planets did appear prior to their grand introduction in June of 1947. One such tale appeared in the September 1931 issue of Wonder Stories, under the title “The Disc-Men of Jupiter.” The passage describes a biological version of the prototypical flying disc:

“Through the smoky yellow veil they made out a strange moving thing that, as they peered, revealed itself as a dark disc, its edge inclined toward them, slowly turning. It was as large around as a tea-tray, and was thickest in the middle, so that its shape was like that of two saucers, placed with concave faces together. Its spinning motion increased and it drew nearer. They could see now that it was composed of living tissue.”

Gross.

AS also published a story in its March 1942 issue that described a saucer-like aerial object five years before Arnold’s sighting cemented the image in the public’s mind. In “Planet of Ghosts,” author David Reed described a space-vehicle that was “a shallow, flat vessel like a saucer.”

Palmer had his own bout with prophecy in the April 1947 issue of AS when he guessed that “within a few years, we will be visited from outer space by a ship that will be seen all over the earth.” He only needed to wait a few months. After Arnold’s sighting made headlines in June, Palmer sought him out.

In fact, his persistence with saucer-celebrity Kenneth Arnold was a major reason the subject gained momentum in the first place. After he “prodded” and cajoled the pilot “into national headlines for two years,” his courtship led to a business arrangement and friendship. The duo later put out The Coming of the Saucers (1952)—a book about Arnold’s experience.

The wave of sightings that followed Arnold’s gave Ray Palmer a sense of vindication. He took it as proof that the type of craft described in his magazine were real. Working three months in advance of each issue’s publication date meant that his first chance at a public victory lap came in his October 1947 column. He humbly seized the opportunity:

“On June 25th (and subsequent confirmations included earlier dates) mysterious super-sonic vessels, either space ships or ships from the caves, were sighted in this country!...AMAZING STORIES therefore takes exclusive credit for telling you about these visitors in a truthful manner… if you want to get the straight dope from now on, read this magazine. It has guts as well as imagination.”

SF editor and Palmer-associate William Hamling added color to the early days of their involvement with UFOS:

“We were in on this business right from the start…We followed up every lead with every person even remotely connected with the “sightings” from that time on. The offices of Amazing Stories became a kind of international headquarters for flying saucer business.”

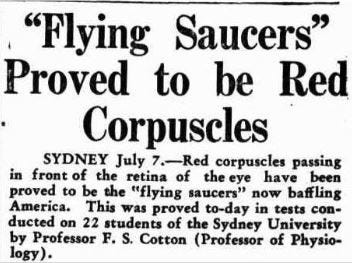

The July 1947 cover of Amazing Stories. While saucers were crashing in the Roswell, NM desert, Palmer’s publication was still featuring tales of space-faring Earthlings.Palmer weighed in on the emerging theories and criticisms from his perch at AS. In order to address the charge that UFO sightings were merely a byproduct of red corpuscles in the eye, he subjected himself to a test:

“Your editor has made some tests to see if the scientists were right about the discs being red corpuscles in the eyeball, and we strained our eyes under the conditions required, and we stand ready to say that you can’t see anything that way, outside of wavy lines and a sort of flicker in the sky.”

When readers began sending him drawings of craft they’d seen, he judged them from a position of power:

“We know that those who have already sent us drawings really did see them, because they all incorporated material which we’ve kept carefully secret. That’s how we check on hoaxers.”

Some contributors to AS treated UFOs less seriously. Berkeley Livingston’s Everything but the Sink (1948) explained that flying discs weren’t the result of advanced technology—they were simply dishes being thrown into our dimension by a gigantic upset alien.

While certain of their existence, Palmer kept an open mind about the saucers’ origins. By 1949 he suggested that they weren’t interplanetary, but “from another dimension…located on this planet… another world like ours, occupying the same space, except that it is larger.”

AS made room for diverse views on the topic, printing articles that assigned terrestrial explanations to reports of flying discs. In “Operation Saucer,” author C. Carns used space in Palmer’s own magazine to dispute some of his conclusions:

“Personally the writer believes that the discs are connected with guided missile research undertaken either here or in some foreign country. Now that the Russians have taken over Peenemunde and numerous German rocket scientists is it not possible that the flying discs are but extensions of their experiments? We think it entirely possible though the editors of this magazine think otherwise. But as we said, each is entitled to his opinion.”

Despite the success of AS, its obsession with UFOs may have been too much for its publishers. According to SF historian Mike Ashley, Palmer’s work catered to a “lunatic fringe”–the antithesis of traditional SF fandom. Perhaps seeing the writing on the wall, and determined to pursue his passion without censorship, he launched his own magazine outside the sphere of Ziff-Davis’ influence. Fate hit the scene in 1948, its first issue serving up reports about UFOs, invisible beings, and giants in ancient America.

Moving further afield from the business of publishing short stories, Palmer’s run on AS ended with the December 1949 issue. New editor Howard Browne took immediate steps to realign the magazine with its hard-SF roots. Ashley’s account reveals how he was “anxious to rid Amazing of the crackpot reputation it had acquired under the editorship of Raymond Palmer,” (Transformations, 2005).

After Fate caught on, Palmer joined the SF pulp magazine Other Worlds in 1949. Unable to resist the allure of the “disc-ships,” however, he converted the magazine into a flying saucer periodical in 1957.

According to editor Ray Palmer: “The staff of FLYING SAUCERS make up perhaps the most informed group of UFO researchers that can be found outside military projects such as Project Bluebook, etc.”Palmer wanted to blend the subjects he enjoyed into an original product—one that fused fantasy with reality. This was in direct contradiction to the dominant hard-SF ethos that still dominated the pulp pages. As Fred Nadis put it in his biographical look at Palmer’s life, The Man from Mars (2013), he “represented the overlap of three circles: science fiction, the occult underground, and the flying saucer crowd.”

Interestingly, this attitude was a far cry from his early opinions about science fiction. In an entry essay he wrote for a 1929 magazine contest (prior to his first job with AS), Palmer expressed the viewpoint that “scientific literature…must contain actual scientific facts and ideas not based on unfounded theory.” Clearly his perspective on the issue had changed during his career as a publisher.

While SF publications continued to find their voice in the 1950s, the start of the Cold War ushered in a heightened sense of suspicion—giving rise to what Nadis calls “the golden age of paranoia.” Palmer’s fascination with UFOs can be seen as a consequence of the era he was living in. As the authors of Close Encounters? Science and Science Fiction (1990) put it: “The fifties witnessed the blurring of boundaries between science and pseudoscience, and the emergence between the two of a deep fascination in the matters concerned with flying saucers.”

SF icon Lester Del Rey also commented on the changes he saw during that era. He explained how the writers of the 1950s had a “tendency to put aside the previous dependence on technology and science” and instead pursue “the quest for magic.” Del Rey blamed Palmer’s infatuation with flying saucers and “various ideas of mysticism and the occult” for subtly modifying the genre—fantastical “psi-fi” to replace the standard hard-SF formula. He admits this new approach was “bitterly resented by most old-time science fiction readers.” (The World of Science Fiction, 1979).

This sentiment about Palmer and his contributions to the field were widespread. He “pandered to freaks,” complained Mike Ashley. For better or worse, “through Palmer flying saucers became inextricably linked with science fiction.” (Transformations, 2005).

Sci-fi scholars Everett and Richard Bleiler offered this trite summation in Science Fiction: The Gernsback Years (1998): “As a science-fiction editor, Palmer was of no historical importance, except as a force for the worse; as an occult proponent, he stands behind the modern outgrowth of irrationality; as a writer, he could well be ignored.” Ouch.

Critics loved taking shots at Ray Palmer for his rejection of the traditional “hard-science” focus of sci-fi. We aren’t sure why he’s dressed like Eastern European royalty in this picture.With his comprehensive coverage of the aerial discs, Ray Palmer occupied a unique place among SF visionaries of his time. Despite the hostility shown to UFOs by other authors, Palmer incorporated them. In a statement felt specifically crafted for his critics, he reflected on how nice it was to see his theories and suppositions adopted broadly.

“…to have your science fiction ideas substantiated. And that flying saucers are real, and no joke. It’s nice, too, to know that after all, scientists aren’t demigods, but just people like we are, and that some of our ideas are as much on the beam as theirs.”

Not all of his contemporaries saw saucers as the scourge of the genre. Sam Merwin Jr., editor of Thrilling Wonder Stories, didn’t harbor a belief in ET occupants, but did acknowledge the additional readership that UFOs helped amass: “Flying Saucers have had much to do with giving science fiction a far wider field of reader interest than the authors, editors and publishers conceived of a decade ago.” Aliens coming to Earth in metallic craft and interacting with humans wasn’t a new concept in 1947. What was new was the terminology and the public’s growing belief that flying-discs were actually arriving in daylight droves.

While Astounding Science Fiction and Amazing Stories were the most renown of the genre, they weren’t the only games in town. Science-fiction’s growing popularity spawned a number of imitators, some of which would go on to rival their predecessors’ success. These magazines would also contribute additional perspectives on flying saucers and provide an outlet between their covers for voices on both sides of the debate.