Writing Off Saucers, Part 1

How early science-fiction embraced and disavowed the flying saucer enigma

It might surprise you to learn that science-fiction (SF) authors don’t particularly care for flying saucers. Sure, their stories are filled with tales about beings from other planets cruising the galaxy in an assortment of space ships—but source material reveals that the SF culture of the 1940s and 1950s was divided over the UFO outbreak. While some writers entertained the idea of alien vehicles littering the sky, John Clute’s Science Fiction Encyclopedia explains why many in the field rejected them: “Most Genre-SF writers are hostile to the extraterrestrial hypothesis – a reaction to the unjustified public assumption that sf writers are deeply interested in ufology.” Guilty by association.

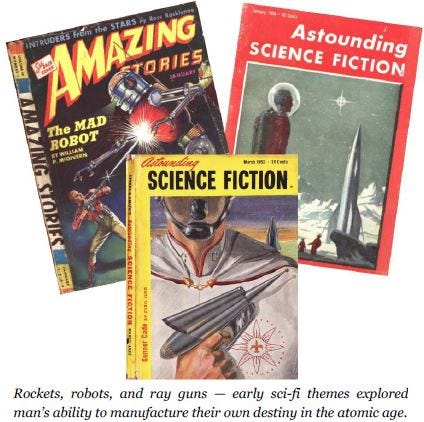

SF devotees had many problems with the idea of flying discs from other worlds. The realm of pulp magazines—where the genre initially found its footing—was a forum demanding adherence to a ‘hard science-fiction’ mantra.

Luminaries like Isaac Asimov and Lester del Rey were dismissive of theories that claimed alien pilots were soaring around the atmosphere. Asimov’s anecdote about his own UFO sighting highlights his apprehension to endorse an ET hypothesis. While on summer vacation with his family, his 11-year-old daughter alerted him to the presence of something strange “hanging” in the evening sky. He was “a firm disbeliever in flying saucers as extraterrestrial spaceships,” and the prospect of seeing an actual UFO filled him with professional dread. After discovering that the object was only a terrestrial blimp, he admitted he was “incredibly relieved!” He “couldn’t bear the thought” that he might have to fess up to an actual encounter. Asimov later put himself unequivocally on the record as anti-saucer: “Don’t you believe in flying saucers, they ask me? ... No, I reply. No, no, no, no, and again no.”

That didn’t stop UFOs from landing in the public consciousness. 1947 was a banner year for unidentified aerial vehicles. Pilot Ken Arnold’s famous June sighting of nine saucer-shaped craft flying over Mt. Rainier provided endless fodder for newspaper headlines. The subsequent worldwide flap solidified the public’s image of ETs piloting metallic discs in our airspace—a theory that divided the ranks of SF.

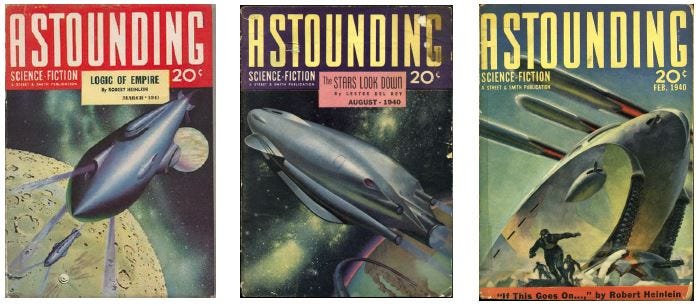

One mastermind behind SF’s early literary zeitgeist was John Campbell Jr. The influential editor of Astounding Science Fiction (ASF) from 1938 to 1971 was an accomplished story-teller in his own right, responsible for the popular tale, “Who Goes There?,” which was later adapted for the big-screen as The Thing. He had a hand in crafting many of the genre’s early successes, using his editorial pulpit to influence the development of stalwarts like Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and L. Ron Hubbard (of Scientology fame). ASF was the pinnacle of publishing during SF’s Golden Age, and aspiring authors were eager to see their words printed in his magazine. Campbell also had opinions concerning those “flying somethings,” and often these views contrasted with the brand of technical, science-reliant “hard-SF” peddled by his stable of writers.

Campbell’s vision of the ideal SF character was a heroic rendition of the “competent man”—someone who operated on logic and made use of cutting-edge scientific concepts. The stories he accepted in ASF echoed that preference. This did not preclude an interest in supernatural phenomena, however. His time at Duke University overlapped with the tenure of ESP-pioneer Dr. Joseph B. Rhine, who founded a parapsychology lab at the school. Campbell admits to testing his psychic abilities with Zener cards, but he wasn’t very accurate at predicting which image was concealed on the other side. According to biographer Alec Nevala-Lee’s book about the man behind ASF: “the entire genre was subtly shaped by his undergraduate encounters with the paranormal.” Despite being the editor of one of the leading hard-SF magazines, his open-minded perspective carried over into his editorial treatment of flying saucers.

In the late 1940s ASF had the largest circulation for any magazine of its type, guaranteeing a sizable audience for Campbell’s columns. His pre-June 1947 comments focused on a postwar nuclear-age and the promise and perils of atomic energy. It wasn’t until the October 1947 issue—a few months after Arnold’s UFO encounter stole headlines—that ASF had a chance to weigh in on the frenzy. Campbell concluded that there was “a fair chance” that the metallic discs were “piloted by visitors from outside.”

And since our immediate solar system wasn’t suitable for the type of life that could develop these craft, they must be “from way outside—interstellar.” He caveats his conjectures by noting that our planet would likely be insignificant to an advanced extraterrestrial society—the universe is vast and Earth is situated in the “galactic backwoods.”

Campbell quickly recognized that it was “considered incumbent on a science-fiction magazine to express some opinion concerning the flying saucers,” and elaborated on why readers weren’t experiencing an “outcropping of saucers in this magazine.” In a piece labeled “Flying Machine,” he explained that ASF had “steered fairly clear of the flying saucer question for several reasons. Basically, it’s a case of no data.” Contending that SF stories were designed to blend an “awareness of the present [scientific] environment” with “the equally valid function of imagination,” he argued that the throngs of UFO reports didn’t fit either category: “The flying saucers have represented that confusion-state that is simply not computable; they are halfway between data-of-now and imagination… They belong in the ‘Maybe file’ with question marks.” These reasons made it hard for a contingent of technically-inclined SF authors to properly deal with the flying discs in their fiction.

Based on the consistent descriptions across sightings, Campbell asserted that “flying saucers are mechanisms”—real nuts-and-bolts “artifacts” in the sky. He also highlighted the frequency of reports in the United States relative to other countries, noting the astute geographic discernment of the extraterrestrial pilots: “It’s a remarkable interplanetary visitor that shows such keen awareness of political boundaries.” This curious fact led the editor to suggest that the aerial objects could be related to America’s advances in nuclear capabilities—or perhaps even the result of a covert government project. He tossed out the Atomic Energy Commission as the perfect front for a hush-hush endeavor like saucer-building: “The parts used in building nuclear reactors, and similar devices, are built under security, and no matter how strange a device it might be, nobody asks questions.”

By 1953, Campbell’s views on UFOs had evolved further. Instead of insinuating the possibility of a secret military weapon, he considered they might be celestial vehicles driven by “telepathically sensitive aliens.” As evidence for this theory, he cited their avoidance of major metropolitan areas like New York or Los Angeles in favor of repeated visits to “Square States” occupying the middle of the country. In “Postulate an Alien Who…,” he surmised that ETs are bypassing the world’s large population centers due to the increased levels of “suppressed tension” radiating from their inhabitants. He suspected an empathic alien race would prefer to land in uncrowded regions of the country because “the reek of tension is the lowest.”

A 1955 missive from Campbell reaffirmed his belief in the reality of flying saucers and urged researchers to expand their approach “outward beyond the Scientific Method.” By the end of the decade, ASF’s intrepid editor remained open to all possibilities. His response to a reader’s letter declared that “they might be scout ships of interstellar visitors … and they might be giant plasmoids of ionized gases of our own atmosphere. They are not the result of any phenomenon adequately known to modern science.”

Another fixture in the pages of Campbell’s ASF was author and book critic, P. Scuyler Miller. His column, The Reference Library, dissected the genre’s latest literary offerings with a healthy dose of opinion. He frequently reviewed the selection of ‘nonfiction’ books about flying saucers. Miller preferred to accept the simplest explanation for the discs (misidentified natural phenomena), but he wasn’t a complete non-believer. He agreed that “this much is clear: there are ‘flying saucers’ and many, or even most, of them are not hallucinations.”

Yet Miller doubted their interplanetary origins. He gleefully highlighted an article by Captain Edward J. Ruppelt, head of the United States Air Force Project Blue Book, that “demolishes some of what has seemed the best ‘evidence’ for saucers as interplanetary vessels.” He labeled Ruppelt’s Report on Unidentified Flying Objects (1956), “the sanest Flying Saucer book in print.” He was sensitive to the stereotype that SF fans were “wild-eyed fanatics who hobnob with little green men,” and aimed to uphold hard-SF principles with his type-written critiques. In Miller’s estimation, “science-fiction readers, of the breed who favor this magazine… can keep our fiction separate from our fact, and while we’re willing to go along with the most fantastic speculations in a story, we bristle like watchdogs if the same kind of thing is served up as fact.”

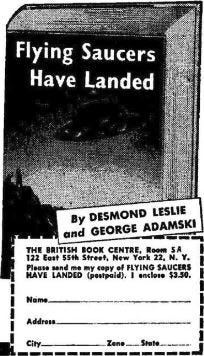

In the April 1954 issue of ASF, Miller surveyed three popular saucer books of the time: George Adamski’s Flying Saucers Have Landed (“extremist;” “occultist”); Donald Keyhoe’s Flying Saucers from Outer Space (“he is also no scientist”); and his favorite of the lot, Harvard professor Donald Menzel’s Flying Saucers, which explained UFO reports as a variety of atmospheric phenomena (“conservative science”).

Of the three, Menzel’s book was upheld by the hard-SF faction as an appropriate treatment of the topic. Author L. Sprague de Camp—who didn’t believe UFOs were “little men in space-ships from Venus”—recommended it heartily: “If you really want to know what is what in Sauceria, Dr. Menzel is your man.”

It follows that Miller was not a fan of ‘contactees,’ or those claiming to have channeled communications with aliens. He felt such stories were personal “revelations,” detached from the principal values of SF. A scan of the latest saucer volumes hitting the shelves in the 1950s led him to conclude: “Flying saucers have taken on the aspects of a cult—very nearly a religion—to many people.”

Why did Miller think so many were susceptible to the occult interpretation? They were “groping for a dogma, an authority, to bolster us up in this uncertain world we’re in.”

When evaluating contactee George Adamski’s body of work, he warned that “if you are one of the many who accept what is written here as the truth, you are going to have to accept certain statements by the Saucer people which are distinctly at odds with orthodox science.” Adamski adherents were a “growing mob of saucer cultists” who believed incredible tales; and Miller was “equally sure that most science-fiction readers do not.”

That ‘damn Adamski’ and the emergence of ‘contactee’ literature in the 1950s wasn’t well received by the traditional sci-fi crowd. He also thought little of early ufologist M.K. Jessup, labeling him an “Atlantean enthusiast” like it was a derogatory term. He felt Jessup was “so manifestly blinded by his purpose, that he often fails to sound even reasonable.” Miller also continued his criticisms of Donald Keyhoe during a rundown of his second book, The Flying Saucer Conspiracy (1955). He was unimpressed with Keyhoe’s “uncritical approach,” and “obvious lack of scientific background when dealing with a scientific subject.” His limited credentials left him “open to any wild ‘explanation’ as having equal weight with the established laws of physics and mechanics”—a sacrilege to scientific sensibility. Conversely, Miller had a kinder assessment of French ufologist Aime Michel’s Flying Saucers and the Straight-Line Mystery (1958), describing the author as “a man who knows something about science and evidence.”

While ASF took an ambivalent stance on the reality of flying saucers, one of its long-standing competitor magazines promoted a different interpretation of the aerial craft. Amazing Stories (AS) and its editor, Raymond A. Palmer, left an indelible mark on the SF landscape—one that nurtured a generational interest in mystical motifs and paranormal ideas in lieu of the scientific method. Palmer’s supernatural-friendly approach would earn him thousands of readers and the wrath of hard-SF aficionados the world over.