Part 1 Here

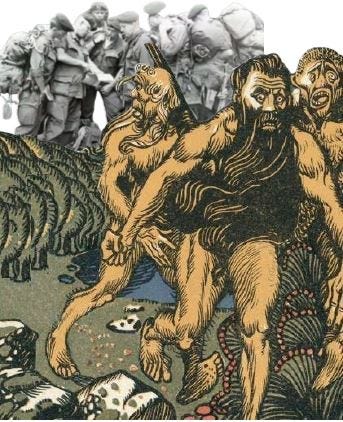

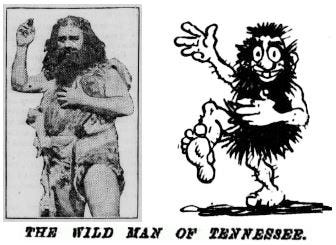

‘Wild men’ are a well-worn legend in the backwoods of Tennessee. A distinct mixture between man and beast, tales of the frenzied ‘wild man’ were recorded in local newspapers of the late-1800s. Many of the recluse-seeking individuals were benign, if freakishly large and unkempt. Others painted them with sinister motives, as The Hagerstown Mail warned of a local ‘wild man’ in 1871:

“He is said to be seven feet high and possessed of great muscular power… His entire body is covered with hair and his whole aspect is most frightful. He shuns the sight of them but approaches with wild and horrid screams of delight every woman who is unaccompanied by a man.”

People living off-the-grid are acknowledged to exist in small numbers on the outskirts of the Great Smokies. Could they be contributing to the unusual wilderness disappearances? Unlikely. Most ‘wild men’ are determined to escape modern society and its residents. Abducting children would mean inviting thousands of ‘outsiders’ into their realm, which seems out of character and doesn’t fit the profile.

David Paulides relies on patterns. Once he identifies a set of pertinent criteria, it becomes easier to find similar cases that fit this pre-established profile. While critics accuse him of “cherry-picking” spooky cases for his books, it’s common practice for researchers to narrow their scope to a specific subset of data in order to understand a larger picture.

Before he became famous for his Missing 411 series, he applied this methodology to the Sasquatch arena. His first book, The Hoopa Project: Bigfoot Encounters in California (2009), was a compendium of sightings and associated data that revealed a ‘cluster’ of Bigfoot encounters centered around the Hoopa Reservation. Based on the information he had amassed, Paulides told the Mount Shasta Herald that he estimated “a current population of 2,000 Bigfoot.”

Paulides’ association with the bipedal cryptid has been hard to shake. While his Missing 411 project is ostensibly about unexplained disappearances (he never implicates Bigfoot directly), most of the links from his website direct back to the North America Bigfoot Search (NABS) store. In fact, the ‘Recent Cases’ section of the Missing 411 website, which highlights “recent cases of people who are missing in the wilds of North America,” hasn’t been updated since 2015. These details give his detractors an opening to suggest Paulides’ motives are less than altruistic; instead of locating lost individuals, they claim he is exploiting victims to promote his brand.

There are plenty of ad hominem attacks against Paulides, but the accuracy of his reporting, along with a refusal to decode the mystery, leave his haters with few avenues from which to attack.

Some see him as the poster child for the adage, ‘correlation doesn’t equal causation,’ chastising the way he emphasizes a missing person’s proximity to things like streams or boulder fields as if there’s some deeper, hidden significance. Critics point out that water and rocks are everywhere in the wilderness—especially in undeveloped areas—so people vanishing in their vicinity isn’t all that surprising.

Paulides doesn’t claim to know for sure what’s behind the odd disappearances in his books, but he does claim to know what is not. At different times, he has ruled out parental “negligence,” “animal attacks,” or “people,” leaving the options open to fringe possibilities. When he’s asked to offer up his best explanation, Paulides “artfully avoids the question of what” (Fortean Times). Frustrating to most pundits, his ability to dodge the punch line comes across as reputationally prudent. If he revealed an interpretation of the events, and was proven wrong, it would damage his credibility and limit the reach of his project. More importantly, by not naming a boogeyman, Paulides leaves much of Missing 411’s mystique intact. Its allure relies on the observer’s ability to project their individual fears of the unknown into the darkness of the woods.

Skeptical Inquirer depicts this evasiveness as “intentional ambiguity.” They’re right in that his non-committal stance purposely allows for any possible explanation to fill the void—a tactic that expands the appeal of Missing 411 to wider audiences than, say, just Bigfoot fans. The thing is, Paulides isn’t obligated to offer a solution to the odd cases he’s identified. Critics might denounce his allusions that paranormal elements are at play, but the fact that David has amassed accurate accounts of rural missing persons is a valuable resource for investigators and search-and-rescue officials.

To bolster his argument that ‘something weird is going on’ in the woods, Paulides reacts incredulously at the bizarre details he’s confronted with. He “can’t believe,” finds it “hard to believe,” and at times even “very hard to believe,” that a lost youngster has traveled for miles without help. He finds similarly remarkable events to be “unlikely,” declaring “there is no possible way” a missing person would behave in some of the strange ways detailed in Missing 411 reports. The tactic can be convincing, especially after reading a string of curated stories that seem to defy logic. If someone’s disappearance “makes absolutely no sense” from Paulides’ perspective, chances are it’ll find a spot in one of his clusters.

Brian Dunning of Skeptoid likens Missing 411 clusters to the Bermuda Triangle—a specific area of land that invites individuals to visit or fly over becomes a hotspot for disappearances (simply because there is more activity there). He goes on to label Paulides as a “Bigfoot evangelist” who simply “[takes] ordinary but tragic events, and [makes] all sorts of insinuations about them to weave an air of undeserved mystery.”

The criticism gets more outlandish.

According to an article in the March 2020 issue of the CTC Sentinel—a publication put out by the Combating Terrorist Center at West Point— “conspiracy theorist” David Paulides contributed to the radicalization of the 2020 Hanau, Germany mass-shooter. In a piece about the shooter’s motives, the authors cite his interest in the Missing 411 mystery as a contributing factor. They argue that the shooter’s belief in these “niche conspiracies,” contributed to the illusion of an expansive “super-conspiracy” involving abducted children and secret government cabals.

Despite dismissing the phenomenon as “paranoid narratives relating to various disappearances of young children across the United States,” based on “unfounded notion(s) that supernatural forces are behind these events,” the Sentinel piece suggests that Paulides’ work may have been powerful enough to “influence [the shooter’s] broader sense of paranoia and anti-establishment mindset.” It’s true that David implicates the National Park Service as either incompetent or complicit in covering-up some missing persons cases, but the article’s dire accusations are a stretch. The charges feel overblown and undeserved considering Paulides hasn’t offered a concrete explanation for the cases he reports. By their logic, the Missing 411 mythos would certainly inspire less harm than the countless episodes of Dateline that feature mysterious disappearances and unexplained murders.

There are also some professional incidents in Paulides’ past that he’d likely rather forget. His time as a civil servant meant his actions were in a spotlight and subject to public scrutiny.

Different sources have documented his exit from the San Jose Police Department in 1996—alleging he was forced to retire after using official police letterhead to solicit autographs from celebrities. Paulides denies the characterization of these events and portrays his departure as amicable and mutual.

A different reputation plagued him during his early days on the force. According to an article published on April 28, 1983 in the Bay Area Reporter, “Officer Paulides of the San Jose Police Department’s Street Crime Unit” was involved in policing practices that were condemned as unfair by a local civil rights activist. Calling him “king of the bookstore detail,” the article essentially charges Officer Paulides and his unit with targeting specific communities in order to lure them into illegal activity. The full BAR piece contains additional details, and it’s important to bear in mind that their portrayal comes from a subjective source and doesn’t necessarily constitute an accurate representation of what actually occurred. However, if there is truth to either episode, they offer additional insights into Paulides’ law enforcement career.

Paulides might be reluctant to tip his hand about the potential reality behind the Missing 411 mystery, but there are some intriguing theories to consider. Could there be a common mental delusion experienced by people—especially children—who lose their way in the woods? This might help explain the bizarre tales told by some impacted individuals. Like the similarities across alien abduction scenarios, maybe things like Missing 411’s frequent tales of animals with human qualities are expressions of an underlying universal experience that can manifest in people who become detached from familiar surroundings.

Or perhaps the explanation leans toward something more paranormal.

Entities in the woods are part of a long and rich tradition across the world. Celtic myths about forest-dwelling pixies absconding with children and gleefully leading travelers off course are an early representation of the ‘trickster element’ that might be at play in the Missing 411 phenomenon. According to a report about pixies in an 1891 edition of the Wichita Daily Eagle, these “mischievous sprites ... derive great pleasure in enticing unwary travelers across the wild moors and hills from the right paths and leading them grievously astray.” This enchantment was known as being “pixie-led.”

Cases like that of 2-year-old Jackie Copeland (1950) out of Pennsylvania hark back to this notion. He went missing from a well-attended company picnic, only to be found the next morning in the middle of “impassable swamps.” He steadfastly claimed that he wandered away from his parents in pursuit of a creature that had been “peering at him from behind a big tree.” He also told of encountering a “throbbing giant” during his night in the forest, reminding us that perception and reality can be extremely unreliable under stressful conditions.

There are other interesting overlaps between what Paulides has compiled and pixie-lore motifs—including the advice to refrain from taking food from the fae-folk. This warning is echoed in Missing 411 mythology by its insinuation that wild berries should be avoided. Additionally, in the same way that clothing seems to play a role in some incidents, an ancient remedy against being waylaid by puckish pixies involved turning one’s clothes inside out to confuse or distract the entity.

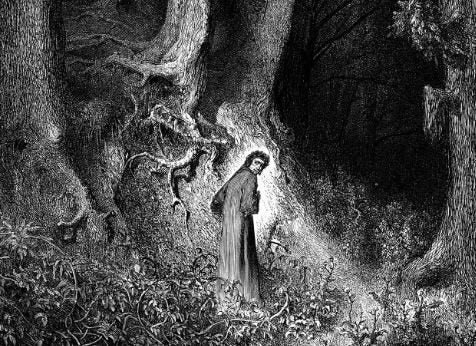

In many ways, Missing 411 is an updated spin on a classic theme—one constructed on humanity’s fear of untamed wilderness and the archetypal ‘dark woods’ of our own psyche. Psychologist Carl Jung saw symbolism in the forest’s “mysterious impenetrability;” a place where “things suddenly appear and disappear, and there are no paths, anything is possible.”

Fairy-tale scholar Bruno Bettelheim likewise concluded that the “forest in which we get lost has symbolized the dark, hidden, near-impenetrable world of our unconscious.” It’s described in a similar manner in the Taschen book, Reflections on Archetypal Images: “The forest, with its exotic forces, is ‘outside’ the inhabited precincts of consciousness.” Missing 411’s woodland setting harnesses the power of this symbolism.

By curating his distinct milieu of cases, Paulides is (perhaps unwittingly) building a contemporary urban legend—albeit one based on verified and accurate accounts instead of ‘friend of a friend’ anecdotes. Drawing from the well of collective-unconscious, his stories come complete with an underlying moral lesson that taps into the timeless parental fear of losing a child.

Paulides’ ability to retell events as “dramatic stories of suspense” qualifies him as a “performer of folklore,” according to the definition laid out by Dr. Jan Harold Brunvand in The Vanishing Hitchhiker: American Urban Legends & Their Meanings (1981). Dr. Brunvand asserts that legends often emerge “to explain the unusual and supernatural happenings in the natural world”—an apt description for the development of the Missing 411 narrative.

The return hike to Cades Cove took place in early afternoon, the sun barely making its presence known through the thick canopy overhead. Walking downhill gives the illusion of an easy return trip, but loose stones and unsure footing makes it deceivingly difficult. A pair of hikers heading the opposite direction paused to hear about the bear cub sighting and eagerly reciprocated a “weird experience” that befell them moments prior at a previous point on the trail. They described hearing a “loud thud” far off in the woods while simultaneously feeling an unexpected burst of air nearby. At the same instant, they both described feeling the pressure change around them. When asked if they’d observed what might have caused these events, they replied that they hadn’t seen anything, but they’d “felt it.” Whatever sensation had them spooked was intangible but visceral.

The same power is inherent in the Missing 411 mythos. Instead of stocking the the impenetrable forest with wild men, witches, or worse, David Paulides reminds us that it’s more disturbing when we don’t know what lurks in the darkness.

While it’s possible that Paulides hams up some of the details and omits others, his fascination with strange missing persons cases in the wilderness seems to be authentic.

On January 9, 1987, the San Jose newspaper The Mercury News reports Paulides and his street crimes unit MERGE being accused of police brutality by the black community.