Where the Wild Things Are: The Missing 411 Mythos, Part 1

‘Clusters’ of people disappearing in wilderness areas around America’s National Parks hint at an ominous and persistent mystery. We hit the trails and analyze the Missing 411 phenomenon.

The rugged path leading to six-year-old Dennis Martin’s last known location starts near a heavily-trafficked area of Cades Cove—the most popular campground in the most visited National Park in America. It’s a stark juxtaposition; an outpost of civilization at the foothills of the uninhabited Smoky Mountains. Yet at 8 o’clock on a Saturday morning, the picnic grounds near the trailhead were all but deserted.

The safety of the parking lot lingers for the first mile of the trek. Then, the commotion of Cades Cove quickly dissipates, replaced by the sounds of moving water and sharply falling leaves. As the trail narrows and begins to climb steeply, the forest’s embrace is all encompassing, and the outside world melts away.

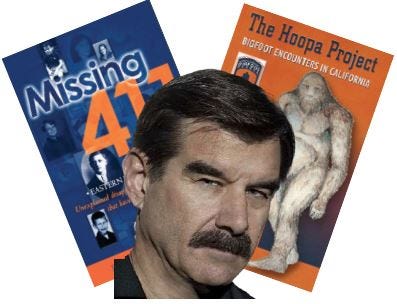

David Paulides looks like a cop. He carries himself with the sureness of a law enforcement officer while sporting the stereotypical police mustache. It’s not a surprise to learn he spent 16 years with California’s San Jose Police Department.

Paulides is best known for a series of books and movies that document peculiar disappearances of people in the wilderness. He gave the project a meaningful yet cryptic moniker: Missing 411. The title is a nod to the total number of missing persons cases compiled in his first two books: 296 males and 115 females (411). While David is careful to tiptoe around suggesting what might be behind these odd disappearances, his premise is clear: something highly strange is causing people to vanish in the woods.

You know when you’ve arrived at Spence Field. The forest has reclaimed most of the grassy bald but there is a sparseness to the meadow that is absent in the dense woodlands below. Clumps of briars, blueberries, and beech trees litter the landscape among rings of pin cherry trees offering up branches full of small red berries.

From the Anthony Creek trailhead, the hike up to the clearing where Dennis Martin went missing is strenuous, gaining over 3,000 feet of elevation by the time the trail terminates at the ridgeline. It feels every bit its advertised 5.2 miles.

Dennis was last seen in the summer of 1969. Family members described how they were within 30 feet of the child as he hid behind some bushes in the open land that straddles the Tennessee and North Carolina divide. Spence Field is perched near the convergence of three separate trails. Eagle Creek Trail ascends from the south, while the Bote Mountain Trail approaches from the north. Both trails merge into the Appalachian Trail, which runs east to west along the top of the mountain’s ridgeline. A backcountry shelter exists less than a quarter of a mile from the field, offering an oasis to the long-hikers and over-nighters traveling through the region. The location is remote but sits at a junction that brings hikers into the area from all directions.

While thousands of people vanish every year, in order to qualify as a Missing 411 case, a certain element of high strangeness needs to be present. Paulides spent countless hours researching potential cases that matched his criteria, then assembled them by geographic locations. Trends began to emerge from the data, allowing him to identify “clusters” of activity—potential hotspots where scores of people have gone missing under various strange conditions.

The person usually goes missing quickly, with no calls for help or cries of distress heard by their companions.

Berries are another frequently cited aspect. Missing 411 cases are often last seen picking berries, recovered in berry bushes, or subsisting off of berries while lost. This repeated pattern is illustrated by the cases of Emma Bowers (1953), a 5-year-old girl who went missing for 60 hours and was later discovered “eating wild berries;” and 3-year-old Alvan Diggan (1942), who became lost while his parents were “working a wild strawberry patch.” Both children were located over 2 miles from their last known locations.

In fact, routinely a Missing 411 person is later found at an odd distance from the point they were last seen. Toddlers that go missing turn up miles away, an unrealistic accomplishment for someone of their age.

Other times, a missing person turns up close to where they disappeared, in an area that had been thoroughly searched. Michael Reel (1983), 8-years-old, was lost for a week near the Smoky Mountains, only to be found in a blackberry patch 2.5 miles from where he vanished. The strangest part of his absence was how he claimed to have spent the time: in a deserted cabin with his deceased grandfather. Authorities felt the boy must have “hallucinated” and was confused (another common Missing 411 trait finds survivors returning in a bewildered state).

Rivers—dry beds or flowing—are a consistent component. Tracking dogs regularly lead search and rescue teams to banks of rivers only to lose the scent. Many times, Missing 411 individuals vanish near, or are later located in, creek beds. These areas have the obvious effect of obscuring footprints and odors from search parties, and their inclusion is curious if only for the fact that many of the missing are too young to have navigated these obstacles on their own.

Clothing also plays a role in the enigma. Missing persons are sometimes wearing red or other bright colors when they disappear. Some Missing 411 ‘victims’ confusingly shed their shoes or other important pieces of clothing during their absence. In one bizarre case that took place in the Smoky Mountains, 16-year-old Geoffrey Hague’s (1970) belongings were found neatly arranged on a rock in the middle of a river, not far from his body. The Boy Scout inexplicably ditched his backpack, survival gear, and most of his clothing, despite the cold winter temperatures. Paulides relates a chilling detail that cements the ‘Missing 411-ness’ of the boy’s disappearance: “Articles inside the pack were laying on the rock or the pack as though someone was taking inventory.”

Another off-putting theme recounted by a minority of recovered Missing 411 children are encounters with hairy woodland creatures—typically bears or wolves—that exhibit human-like behavior. A hair-raising example comes out of Walhalla, Michigan, a small town located 20 minutes from the coast of Lake Michigan, where a young Katie Flynn (1868) went missing from a lumber camp run by her father. She was found the following day wearing only one shoe, standing on a downed tree that had fallen across a nearby river. The men who found her said they witnessed “a huge black bear jump into the river and disappear across the other side.” When questioned about the events, Katie told rescuers: “Big dog came up to me, took me in his arms and walked away with me.” She explained her misplaced shoe this way: “The big dog ate it.”

Articles published decades later about the ordeal provide additional unsettling details. Katie told her father how “the big black thing ... held out its paw and she caught hold of it and it had walked away with her.” Later in her story, the girl recalled a moment when the bear offered her a paw full of berries to eat before pushing “a big pile of leaves close to her and lay down close to her and during the night had tried to cover her with its body.” A river, hairy anthropomorphic mammals, berries, and a missing child—the perfect recipe for a Missing 411 case.

The way Dennis Martin vanished off the face of the earth resonated with David Paulides. The longest chapter in Missing 411: Eastern United States is dedicated to the incident; it haunted him to such an extent that he traveled to Tennessee to interview Dennis’ father face-to-face.

There are no new revelations about the boy’s disappearance. After he went missing during a game of hide and seek with his newly minted friends (also eerily sharing the last name, Martin), the Park assembled the largest search and rescue response in its history. The effort brought out over 1,400 people, including a contingent of Army Special Forces; helicopters and bloodhounds were deployed, the FBI was consulted, and psychics offered their services—all hoping to locate the youngest Martin. Sadly, no trace of Dennis was ever found.

A half-century later, on a warm October weekend, only a handful of other hikers were making use of the path to Spence Field. The lack of people might have been a byproduct of the torrential rains that had fallen during the week, leaving the trail soggy and difficult to navigate. Reports of aggressive bear activity in the area likely also contributed to the dearth of hikers. Campsite 9 had been closed altogether due to the elevated risk and signs were posted at different points along the trek, alerting hikers of recent attacks. True to the reports, a black bear cub was spotted less than fifty yards ahead on the trail, but it quickly darted off the path to avoid further detection.

Some speculate that an animal was involved in Dennis Martin’s disappearance. While it’s possible a bear or bobcat could be responsible, the theory loses steam when considering the amount of noise and evidence that results from wild predator attacks.

The animal-attack theory stems from an encounter reported by the Key family, who were visiting a different area of the park around the time of day that Dennis went missing. The Keys were about 9 miles downhill from where Dennis vanished when they heard an “enormous, sickening scream” coming from the woods. Mr. Key later told the Kingsport Times that he “saw a man behind the bushes … keeping behind the leaves. He was definitely trying to keep from being seen.” Upon investigating the area where the man was spotted, Mr. Key said he found a slip of paper that seemed to have a crude map drawn on it with a portion marked off as “camp area.”

A different report of the incident from the Knoxville Journal included a variation of Key’s story:

“We heard an awful scream that sounded like someone in trouble. There was a stream there. As we were going up to it, one of my boys said, ‘Look daddy, there’s a bear!’ I looked. It wasn't a bear. It was a man. I didn’t get a good look at him because he seemed to be trying to stay hidden behind bushes.”

Considering the imposing forest terrain and the distance from Spence Field to where the Key family was hiking, park rangers and officials doubt that the Keys saw anything related to Dennis’ disappearance.

Details have emerged and evolved in the ensuing decades. During Paulides’ 2011 interview with Mr. Martin, we learn that Dennis’ father believes his son was taken from Spence Field. His suspicion stems from a conversation he had with Mr. Key about the man his family reported seeing that day. During their meeting, Key told Martin that the individual they saw appeared to be “carrying something on his shoulder” as he picked his way stealthily downhill.

The conversation inevitably progresses from bears to the ‘wild man,’ or Bigfoot, when discussing the merits of the Key family’s sighting.

Part II

https://theobservermagazine.substack.com/p/where-the-wild-things-are-the-missing-03d?utm_source=url

Do you have a ink to part 2?