The Ringmakers (Part 1)

“Any people who expend so much effort to terraform the land were in dialogue with forces we cannot see and measure.”

For ten bucks you can visit one of the oldest sacred sites in North America. A single Alexander Hamilton gets you into the Hilton Head vacation community harboring this 4,500 year-old ceremonial center. Once inside, head toward the forest preserve—a slice of green-space impervious to the beachgoers and golf carts patrolling its exterior. There, just past the wastewater treatment plant, sits a large circle of mounded shells. It’s a strange spot to find the remains of something so ancient. Constructed around the same time as Stonehenge, the Sea Pines Shell Ring may not look like much these days, but for thousands of years it was a center of ritual and cosmological symbolism.

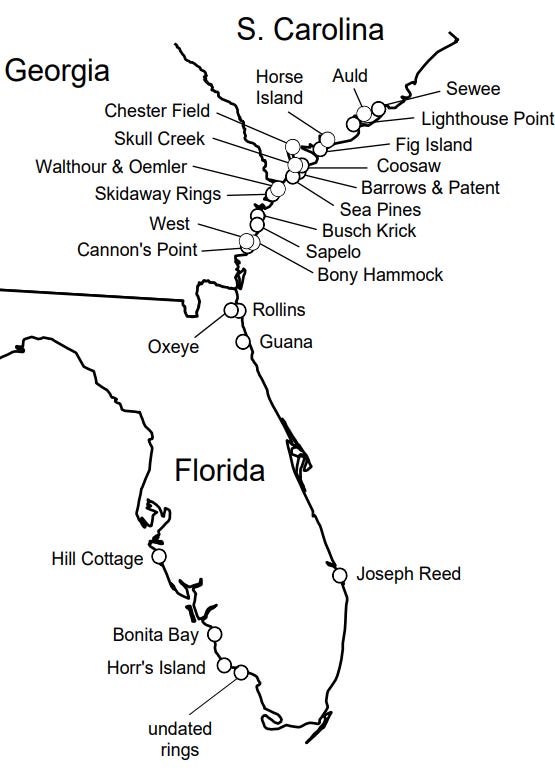

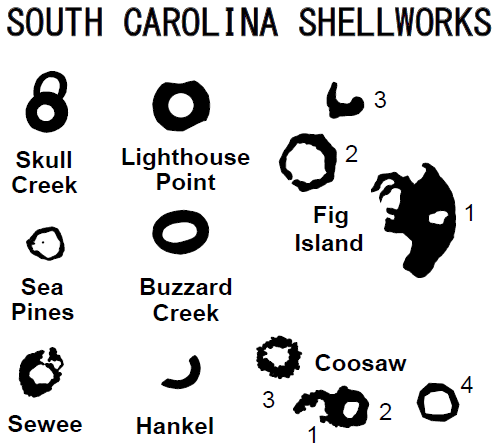

The Sea Pines ring is one of more than 50 known shellworks located on the Atlantic coast between South Carolina and Florida. These installations are made up of millions of oyster and clam shells deliberately arranged in circular patterns. Some measure hundreds of feet in diameter. Dating back as far as the Late Archaic (~5,000 years ago), these impressive structures are the earliest large-scale monuments of their kind in the United States.

Those are about the only details experts can agree on when it comes to South Carolina’s shell rings. A debate rages (as much as one can rage among academics specializing in Archaic-period Southeastern customs) about their true purpose. Conventional theories embrace mundane explanations ranging from ancient trash piles to water collection systems—but compelling evidence suggests that they were constructed for ritualistic purposes. As archaeologists continue to uncover sacred artifacts, signs of ceremonial feasting, cremation, and even possible astronomical alignments, the real history of these enigmatic rings is starting to take shape.

Only a handful of shellwork sites are open to the public, so I explored as many as I could while road-tripping in South Carolina’s low country.

One of the more visible shell ring examples is Green’s Shell Enclosure on Hilton Head’s northwest coast. It’s nestled within a neatly kept park, just steps from a playground with an impressive basketball half-court. The shell enclosure is bordered by a private cemetery, a telling sign that the sacred nature of the land was recognized by future generations. Several other shellwork sites share this pattern: modern burial grounds bordering ancient ceremonial spaces. When I visited at 10 a.m. on a Wednesday, the place was empty. A clamor of roosters and cardinals greeted my arrival.

Built centuries later than the installation at Sea Pines, Green’s Shell is an echo of the same ceremonial ring-building tradition. The rings once stood more than five feet tall and 20-30 feet across. Today, they look like large speed bumps in the middle of the woods. If we’re being honest, none of the accessible shellworks will make your jaw drop. Time and the elements have taken their toll and a lot of these ancient structures have faded into the landscape. Without interpretive signs explaining what to look for, they could easily go unnoticed. They reveal their significance the longer you linger. Away from the din of civilization, the atmosphere becomes charged. The site isn’t abandoned—it’s waiting.

I walked around the short trail a few times, hoping a different vantage point might uncover some long forgotten purpose behind the design. The excursion ended abruptly when a persistent noise in the brush (probably an alligator, since I assume every mysterious coastal sound is an alligator) sent me hurrying back to the safety of the parking lot. The visit was a welcome respite from the bustling island, but the site’s condition made it difficult to investigate.

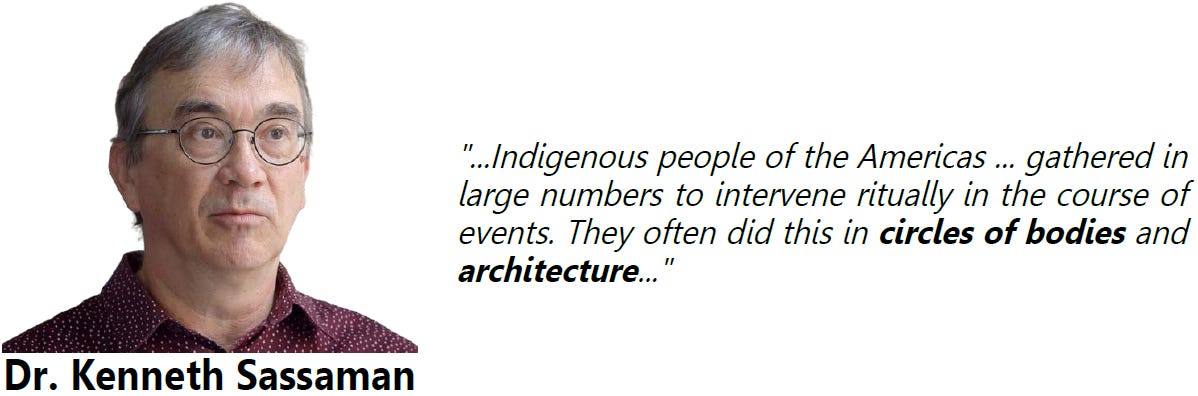

To get a clearer picture of the history behind these puzzling shell structures, I needed help. Kenneth Sassaman, PhD is an OG in the “shellworks-are-ceremonial-sites-not-kitchen-scraps” discussion. He’s Professor of Archaeology at the University of Florida, has authored multiple books and articles about Archaic customs and lifestyles, and is uniquely qualified to weigh in on the topic. Dr. Sassaman is convinced that shell rings were sacred sites used for communion with the supernatural: “Any people who expend so much effort to terraform the land were in dialogue with forces we cannot see and measure.”1

In my email exchange with the gracious academic, he presented convincing evidence for their ceremonial and religious significance: “‘Natural’ features on the landscape appear to have inspired ritual practices because of perceived connections between the Upper World and This World and arguably they were portals to travel between worlds, much of it related to world renewal. Shell rings, mounds, etc. may have been instruments of ritual intervention.”2

Dr. Sassaman gets no argument from us. His work supports the premise that ceremonial practices were associated with the creation of ritual infrastructure like shell rings. This idea gets a boost from the work of another highly respected name in the Archaic shellwork game, Matthew Sanger, PhD. Dr. Sanger is the curator of North American archaeology at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, and an authority on how people lived during the Archaic period. Like Dr. Sassaman, he has hands-on experience excavating shell formations across the Southeast—including the one at Sea Pines. Sanger describes them as “revelatory locales;” spots on the landscape where ritual behavior “established communication with non-human forces.”3

Clues suggest that the structures may be a type of sacred architecture. One indicator is the choice of building material. Revered for both their beauty and functionality, shells were used in Archaic artwork, jewelry, and even as tools. They were deeply symbolic objects—their spiral shape reflected life’s pattern of birth, death, and renewal. Since shells came from the ocean, they were connected with the underworld and supernatural forces; they also “evoked the stars” and were seen as reflections of the cosmos.4 Their duality acted as a bridge between the terrestrial and the celestial domains, making them a particularly symbolic medium to use when constructing a ceremonial site.

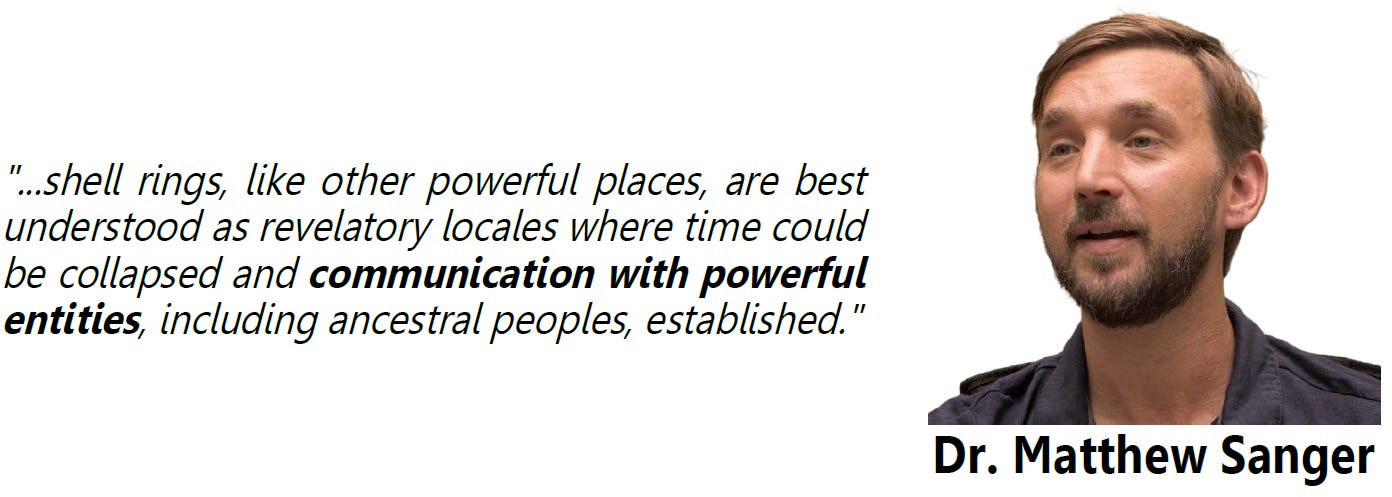

The fact that many shellworks are circle-shaped further hints at their intended purpose. Circles visually represent the cycles observed in nature. Significant events like the change of seasons, the cycle of life and death, or the predictable circuits traveled by heavenly objects were seen as a circular process. Shell rings were laid-out in a deliberate manner so as to illustrate this rhythmic relationship between the past, present, and future.

The circular layout created a natural gathering place in the center. According to Dr. Sanger, this layout imbued the central plaza with supernatural power: “The formation of powerful center points is also a means by which many Native American groups likewise created ‘portals;’ points where time, space, and social distance between human and non-humans can be folded, collapsed, extended, traversed, or otherwise manipulated.”5

The ring-shaped structures also paid tribute to the most important object in the sky: the sun. Shell rings commemorated the solar disk, its annual cycle, and the circular horizon from which it rose and set. The stars, moon, and planets were all players in the grand cosmic theatre, but the sun was the lead character. The sun’s position on the horizon informed ritual observances and dictated social rhythms throughout the year. It heralded changes in the weather and signaled the time to plant, harvest, hunt, or migrate. Events like solstices and equinoxes were ritually observed by most groups. If celestial alignments were found alongside early shell formations, they would provide ammo for the rings’ ritual significance.

This begs the question: did the Archaic Southeasterners take their sun deification a step further and encode astronomical alignments into their sites? This possibility is often dismissed by mainstream scholars, but there’s no doubt that traditional cultures were in tune with heavenly objects.

Cue Dr. Sassaman. His research of solstice-aligned dunes along Florida’s northern Gulf Coast, confirms that summer solstice rituals occurred there between 450 and 600 CE.6 Though the ceremonial site was built millennia after most of South Carolina’s Archaic shellworks, its cosmological symbolism echoes those earlier traditions.

With all this in mind, we turned our attention to the area’s most pristine example of ritual shell circles: the monuments of Fig Island.

Oh boy, what a cliff hanger! Part 2 coming soon!

E-mail correspondence between Dr. Kenneth Sassaman and THE OBSERVER, April 2025.

E-mail correspondence, April 2025.

Sanger, M.C. “Joining the Circle: Native American Philosophy Applied to the Study of Late Archaic Shell Rings of the Southeast United States.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 28:3, p. 737.

Claassen, Cheryl. “Shells Below, Stars Above: Four Perspectives on Shell Beads.” Southeastern Archaeology, 38:2, p. 92.

Sanger, “Joining the Circle,” 756.

Sassaman, Ken et al, “Maritime Ritual Economies of Cosmic Synchronicity: Summer Solstice Events at a Civic-Ceremonial Center on the Northern Gulf Coast of Florida.” American Antiquity, 85:1, pp. 22-50.

It is so sad that sad ancient sites in North America are overlooked or dismissed out of hand by establishment archeology. I think they are too hung up on the Old World, New World theorems.

It might turn out that the New World is actually older than the Old World, and the Old World is actually a really ancient world. Thanks for bringing these ancient sites to the forefront and introducing us to these progressive scholars. YOU GO OBSERVER!

Awesome issue! I'm so fascinated with the early civilizations of North America. Growing up in southern California this topic was never brought up in school and I find that a shame.