The Lure of Lake Monsters, Part 2

Part 1 Here

Stories about bizarre animals kept surfacing in far-flung locations around the “Great Lakes State.” According to the Isabella County Enterprise, “a huge sea serpent” was terrifying the population near spring-fed Indian Lake, in Michigan’s southwest (10.14.1898). With no inlets or outflows from the 500-acre lake, the unlikelihood of their newest resident was proven days later when the Evart Review revealed it was “an otter and a muskalonge”—a type of fish that can grow up to 6’ on occasion (10.28.1898). If one was attempting to eat the other, the intertwined pair would make a remarkable and unprecedented sight for spectators.

A huge muskie (well over four-feet long) caught near Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is pictured in this 1920 ‘Outdoor Life’ photo.The legend of Cass county’s unknown beast didn’t end there—the 12-footer was spotted the following year as well. The Gladwin County Record provided additional details about its behavior, noting an ability to “propel itself through the water like an arrow” (7.21.1899). Its presence left lake-goers anxious, fearing that “it might suddenly rise some time under a boat, capsize the occupants, and possibly kill some of them with its tail in its effort to get away.”

The Cheboygan Democrat notified readers on August 12th, 1899, that a serpent was making itself comfortable in Black Lake—the state’s seventh-largest inland body of water. Situated near the Mackinac Straits, it’s connected to Lake Huron by way of a large river that could provide upstream access for a wide assortment of aquatic anomalies.

Serpent tales continued into the new millennium, although newspaper coverage slowed considerably. An article from the Milford Times detailed the return of an unknown reptile to the confines of Gull Lake in western Michigan—coincidentally the same year that intercity train service began linking the resort community with the busy Michigan cities of Kalamazoo and Battle Creek (8.25.1900). It’d been 7 years since a serpent was last seen in the area, and residents weren’t thrilled to hear about its comeback tour. They were reportedly “purchasing dynamite to explode in the lake in the hope of bringing the ‘monster’ to the surface.” Some housewarming gift.

In the summer of 1903, something was spotted in southeastern Michigan’s Zukey Lake. The body of water is part of an inland chain that slowly winds its way into Lake Erie, supplying an ingress for a wandering serpent to explore. Details from the Saline Observer suggest that the beast measured 80’ and was “capable of swallowing one hundred people,” (6.25.1903).

On August 19, 1905, the Alpena Evening News reported that “a well known Kalamazoo business man” observed a “gigantic reptile” at least 10’ long in Barton Lake—a 53-foot-deep cavity cut into Michigan’s southwestern countryside. The creature allegedly carried its head “a foot above the water,” and was frightening enough to keep vacationers swimming in the shallows. The lake feeds the Portage River as part of a convoluted waterway that eventually spills into Lake Michigan—another entry point from the Great Lakes.

A year after the Loch Ness Monster gained popularity in 1933, the Northport Leader documented the recovery of a hoaxed serpent from the Lake Michigan shore town of Ludington (11.1.1934). The keeper of the Big Sable Lighthouse was walking the beach when he discovered the remains of an “expertly painted” head and mid-section designed to wriggle like a snake in the open water.

Snot Lake—located in the middle of the state—was allegedly bothered by its own 22-foot-long critter. According to the Clare Sentinel, two conservation officers staked out the lake until they nabbed their prime suspect: a rambunctious otter (9.25.1936).

Just a false alarm? Maybe—but the locals weren’t convinced, and monster stories persisted until the following year when the Sentinel ran a breathless tale under the headline: “Snot Lake monster Subdued by County Officers,” (9.3.1937). Instead of a savage serpent, the civil servants apprehended “a huge clump of lily pads with their uptorn roots floating on the water.” While some locals breathed a sigh of relief, others saw the annual attempts and lack of results as proof that the Serpent of Snot Lake was still on the lam.

Sightings around the Great Lakes slumped in the second half of the 20th century. While perennial hotspots around the globe continued to draw interest, obscure ‘local legends’ were subsiding. An uptick in human activity might be partly to blame—instead of generating more sightings, the additional commotion might’ve caused the cautious creatures to withdraw.

Despite the lull, sporadic reports were still featured in local newspapers from time to time. On August 14, 1952 the Leelanau Enterprise-Tribune documented a “sea monster” chase that took place in Northport Bay, an inlet on northwestern Michigan’s “little finger.” Two tourists followed something that appeared to be 6’ long and “swimming noisily” 50-100 yards off the shore. One witness claimed it looked like a bullhead (catfish), but swam “with a motion like a breast stroke.” The object reportedly moved across the surface of the water faster than the pair could run—a good thing for the creature given the fact that one of the pursuers was armed with a butcher knife.

The Enterprise also told of the strange encounter had by a young man living with his parents on the shores of Lake Leelanau. A June 6th, 1963 article led-off by asking its readers: “Is there a sea serpent in Lake Leelanau?” The inquiry came after 15-year-old John Gauthier sighted an unknown water animal with “a huge head, about a foot wide and with two large protruding eyes.” The creature popped out of the water about 100’ away from where he stood on shore, allowing him to watch as it submerged and reappeared in different spots down the lake. He put the dimensions of the dark-colored object at approximately 10’ in length. The Enterprise speculated that it might be “a giant muskie, or perhaps a large sturgeon — or, of course, a sea serpent;” but no definitive conclusion was ever reached.

Interestingly, the story has a precedent from 1910, when William Gauthier—an ancestor of John’s?—claimed an earlier encounter with the Lake Leelanau monster. The tale was collected by Scott Francis in his book Monster Spotter’s Guide to North America (2007), and it tells how William was fishing a shallow area of the lake when he attempted to tie his boat to a nearby tree jutting out of the water. Instead of a makeshift anchor, the “tree” quickly revealed itself as an aquatic creature whose head and neck extended 5’ above the waves. Both boy and beast bailed quickly, and William watched as the animal’s large frame swam under his boat toward deeper corners of Lake Leelanau. Only recently separated from the deep waters of Lake Michigan by a slight dam built in the mid-1800s, the lake is prime real estate for a refuge-seeking cryptid.

“Petoskey’s Got It”

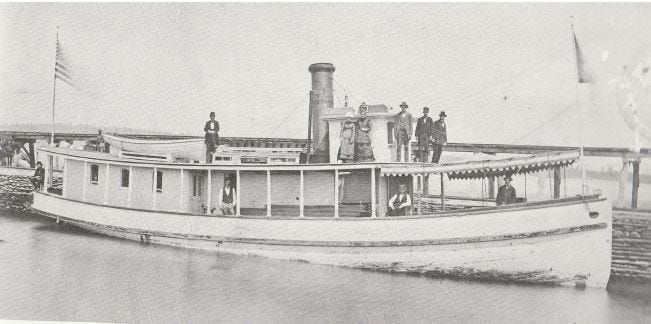

In northwest Michigan, the crystal clear waters of Little Traverse Bay off the coast of Petoskey proved to be an abundant source of sea serpent sightings throughout history. In 1890, residents spotted a monster that was to become a constant fixture in the area. The Grand Traverse Herald declared that “Petoskey’s Got It,” retelling an account out of that city by the witnesses aboard the steamer, Clara Belle (7.10.1890). The captain and crew reported seeing a 40-foot-long object sporting “three huge humps” playing in the boat’s wake. Curiously, they said that the animal’s face didn’t look much like a fish or a snake (a characteristic that would be repeated by a witness years later, leading to assumptions that a marine mammal might be involved). On the last day of July, the Herald reported that the 40-footer was spotted up the Lake Michigan coast, near the town of Harbor Springs.

Thar’ be serpents. The ‘Clara Belle’ as it looked in 1870. The vessel had an early encounter with the infamous Petoskey cryptid.In 1895, the Petoskey Record reprinted a long piece from the Detroit Journal that investigated the possibility of a monster in their midst (1.30.1895). Sightings were rehashed on paper, images were drawn from witness descriptions, and the town did its best to solidify the reality of the beast in their bay. “Reputable citizen” H.M Wilcox told the reporter about the time he saw a 100-foot-long object with flippers that had the ability to raise its head 2-3’ out of the water; Dr. Worden testified to the veracity of the “water monster” after seeing it from the deck of a steamer himself. Asked whether it resembled a fish or a snake, the doctor replied: “It didn’t seem exactly like either.” He went on to describe an animal with a square head, “like a cow’s,” and amphibious looking legs, “like flippers, or lizard’s feet.” The pictures accompanying the article depict an animal that resembles a familiar variety of long-necked cryptid known as a “water horse.”

An addendum to the article informed readers that area officials had commissioned “a force of fishermen” equipped with large fishing nets in hopes of catching the creature once the ice thawed.

Shortly after the article saw print, questions arose about the authenticity of Petoskey’s serpent. Some implied that confused locals had been fooled by a discarded sail and mast floating animatedly in the bay. The Isabella County Enterprise reported that the monster was simply a mistaken cedar log, stuck in a sandbar and given life by the motion of the passing current. (6.14.1895).

The Traverse Eagle, a paper from Petoskey’s “sister resort town” to the south, rejected the hasty attempts to explain away their neighbor’s waterlogged wonder. A scolding editorial demanded “stronger proof than has yet been produced to make us believe that the Petoskey sea serpent is not the genuine article.”

Indeed, rumors of its death proved to be greatly exaggerated—shortly thereafter, a new sighting was recorded by the crew aboard the Adrienne. They joined a large crowd gathered on shore to watch as an enormous object “wriggled about in the water near Harbor Point,” (Saline Observer, 6.6.1895).

While most journalists adopted a light-hearted approach to the subject, monster hunting wasn’t always fun and games. A travelogue printed in the Pontiac Gazette hinted at a dark side to Petoskey’s sociable serpent (8.2.1895). Speaking with an “esteemed” citizen of the town, the author learned “the most blood-curdling theory about the monster’s diet”—but the details were so offensive that he refused to elaborate any further.

Regardless of the creature’s ferocity, the city celebrated its migrating monster by constructing a 108-foot-long replica complete with flapping wings and nostrils that spewed fire and smoke. The moniker was also bestowed upon their local baseball team—the Petoskey Sea Serpents—who were known to carry a 30-foot facsimile of their namesake.

Looking more like a sea dragon than a snake, the serpent from Little Traverse Bay was memorialized as a parade mascot. The monster was powered by three cars hidden beneath the hand-painted canvas.After defending Petoskey’s creature credentials earlier in the season, Traverse City notched its own serpent sighting in 1895. A July 15th report relayed the account from two men who were checking their fishing nets in Grand Traverse Bay. Suddenly, they came upon an “immense monster under water, being as big as a hogshead, with its upper surface curved like a great hump.” A sentence in the July 5th Clare Sentinel and the Democrat-Press provided the story along with a potential explanation—they announced that “the citizens of Traverse City have discovered a genuine sea lion in the harbor.” (More on sea lions later.)

In June of 1897, two men working just up the bay from Traverse City spotted the annual visitor in the waters near Omena. The Daily Eagle’s report was well received by surrounding lakeside communities since the arrival of the creature attraction meant that “the resort business of the north is now assured.”

In 1901, the Petoskey Democrat claimed that eagle-eyed residents of Harbor Springs saw the familiar serpent undulating in Little Traverse Bay. The animal was described as being anywhere from 40 to 150’ long with “the head about the size of a horse’s.” While the city’s “splendid summer attraction” weighed its housing options, its legend expanded. The Democrat observed that “the number of persons who believe indisputably that such a monster infests Little Traverse Bay is growing larger every day.”

Years later, a report appeared in Traverse City’s Evening Record about a conspicuous cryptid “sunning itself” in the Boardman River—a small tributary of Grand Traverse Bay (7.17.1903). The paper admitted that the stationary, “horrid green monster,” seemed more like a submerged mass of algae and seaweed dancing in the current than a true serpent, but in a testament to the power of human imagination, the aquatic curiosity still managed to attract crowds of inquisitive onlookers.

By 1948, flying saucers had invaded headlines around the world, and the Sutton’s Bay Courier sounded left-out over the absence of UFOs in the skies over Grand Traverse Bay: “None are reported seen here as yet.” Still, the column remained optimistic about their chances, comparing the existence of flying saucers to that of lake monsters: “...like the ‘sea serpent’, sooner or later, one should be seen” (7.29.1948).

Petoskey’s serpent made its customary pilgrimage to Little Traverse Bay that same summer. The Traverse City Record Eagle sounded like a jilted lover when it broke the news that the creature had selected the adjacent cove as its preferred lodging: “We feel ashamed to think that Petoskey beat Traverse City to the annual sea serpent story” (7.17.1948). The Eagle went on to describe the recent iteration as a 60-foot-long beast with a “sharp tail…horns, and is dim green in color.” Writing facetiously, the piece concluded by admitting that Traverse City city had all but abandoned the “sea serpent business” since it was hurting the area’s tourism: “Summer guests started going to places where there were no monsters.”

Serpent Stories

Many Great Lakes cryptids never made the local press, existing only in firsthand accounts shared between members of close-knit shoreline communities. In his seminal work on northern Michigan mythology (Bloodstoppers & Bearwalkers, 1952), folklorist Richard Dorson recorded some of the lesser-known legends circulating amongst the residents of the state’s Upper Peninsula. He sourced a couple of stories about serpents from long-time Munising resident, Bill Powell. Situated on unforgiving Lake Superior (1,333’ deep), Powell’s hometown was an important port and its proximity to the water meant fishing was a major source of both income and food.

Powell details an 1876 encounter told to him by his father and brother. One night, while the pair were “jacklighting” for deer on Au Train Lake, their brightly lit torch illuminated something unexpected in the water:

“This creature, like nothing they had ever seen; circled the boat two or three times; he was about a couple of feet out of the water; they could hear his teeth chatter. It couldn’t be a turtle because it buzzed so fast. They hit it with a hardwood paddle, sounded like hitting a rock. It went down to the bottom. There must have been lots of it in the water, since it kicked up quite a little wake.”

Dorson went on to corroborate Powell’s next lake monster anecdote with a different area resident. Angus Steinhoff was a member of a two-man fishing crew trolling the waters of Lake Superior in 1926 when he spotted a fast-moving animal moving across the water:

“It was some kind of a fish or something that made a wave like an airplane or motor boat. It went faster’n we could travel … It resembled a goose or a loon, but bigger; traveled to beat hell, spray shooting out on both sides … we tried to catch up with it; it’d wait for a little while, we’d gain, then it would go like hell.”

Steinhoff’s partner was a lifelong angler and had only witnessed something like it once before—“a reptile in Sweden that made a similar wake, from wig-wagging” (an adorable colloquialism).

Sea Lion Shenanigans

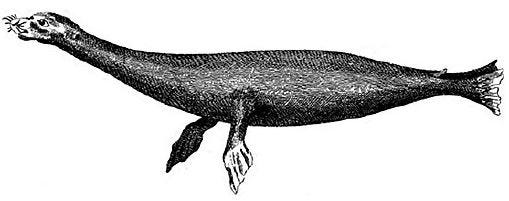

While newspapers insisted on labeling them “serpents,” not every strange creature displayed the characteristics of an aquatic snake. Many witnesses describe “serpents” with hair, whiskers, and other mammalian traits. In Field Guide to Lake Monsters, researchers Coleman and Huyghe propose that “monsters” like these might be a variety of giant pinniped known as a long-necked seal.

This theory was also considered by Peter Costello, author of In Search of Lake Monsters (1974). He argues that water temperatures in regions like the Great Lakes are too low for a coldblooded reptile to survive, suggesting “only a mammal with a fur coat and warm blood is really suited to such an environment.”

One possible pinniped-perpetrator fitting this description is a sea lion. After a large specimen was seen repeatedly in the Mackinac Straits in the 1800s, speculation spread that it might have recently escaped from a Chicago zoo. Since then, stories about fugitive sea lions in the Great Lakes were recycled in various forms, eventually gaining status as a myth.

One of the earliest mentions of this Windy City origin story comes from a Milford Times piece that declared a “sea lion” sighted in the Lake Michigan port of Ludington was “presumably the one that recently escaped from a Chicago park” (11.5.1892). The gripping narrative about Chicago’s missing marine mascot was well-documented in the local press, who described how the poor creature was minding its own business when it drew both attention and projectiles from a group of ne’er-do-wells: “After being well stoned by a crowd of boys it slid into the water again and disappeared.” Note that this rendition was printed in 1892—a year before Chicago’s 1893 World’s Fair—which, in subsequent versions of the yarn, becomes the source of the wayward sea lion.

Lake Huron also yielded reports of something sea lion-like in Saginaw Bay. The town of Pinconning claimed to see it in August of 1894, but the Gladwin County Record hesitated to endorse the sighting, instead insinuating that it was due to the “[p]eculiar effect Pinconning whiskey seems to have” (8.31.1894). Over-consumption was commonly blamed for inspiring people to see strange lake objects—serpent or otherwise.

The sightings continued in 1893—the same year Chicago hosted the World’s Fair on the shores of Lake Michigan. The Cheboygan Democrat told of an encounter with the hairy beast in Grand Traverse Bay by the crew of the steamer Lawrence (6.24.1893). The local Grand Traverse Herald suspected that their “strange visitor”—nicknamed “Jack the Ripper”—was likely in town for the impending tourist season (7.20.1893).

A detailed report in the Herald from the proceeding summer seems to affirm the sea lion suspicions. Multiple witnesses observed one having “a jolly good time” sunning itself on a rock some yards from the shore. Since the creature was out of the water it was clearly visible to its audience—especially with the aid of a “glass” to magnify what they saw (6.27.1895).

The Herald heralded the arrival of the bay’s acclaimed-aquatic again in 1896, noting that its “shaggy” presence off the coast of Cheboygan, in Michigan’s northern Lower Peninsula, meant it was only a couple of weeks away from “it’s marine domicile near Traverse Beach hotel,” (7.16.1896). An article from the True Northerner was also certain that people seeing sea lions in the Cheboygan River were witnessing the famous Chicago pinniped—except they allege that it had just escaped in 1894, a year later than earlier variations (7.2.1896).

By mid-August, as the weather started to fade and beaches became less-crowded, the Grand Traverse Herald reported that the sea lion was migrating south—down the Lake Michigan shoreline to the village of Manistee (8.13.1896). The editor optimistically reassured readers that as surely as the seasons change, their familiar animal friend would return with the sun: “back again at his old haunts ready to receive visitors.” Tragically, this prediction would not come to pass.

Weeks later, the Saline Observer reported on the disastrous result of the sea lions’ layover (9.3.1896). During a jaunt up the Manistee River, a local man allegedly shot and killed the beast by firing upon it from the banks. Upon receiving news of the tragedy, the Grand Traverse Herald victim-blamed the creature for visiting the wrong neighborhood: “...in an unlucky moment it fell into evil ways and went visiting over to Manistee. As might have been expected, it was not appreciated there” (9.3.1896). Mourning the “brutal murder” of their “pet attraction,” the paper commented on the “feeling of sadness and gloom” running through the bay-side town.

On December 24th, perhaps hoping for a Christmas Eve miracle, the Herald told of “a terrible monster, twenty feet long, with the head of a dog and the tail of a fish,” seen on the state’s west coast, 25 miles upstream from where the Grand River empties into Lake Michigan. The boys who saw the animal said that it “would bark like a dog and swim like a fish”—traits that sound decidedly sea lionesque. Was the ‘Manistee Massacre’ a hoax? Did the scrappy-sea lion pull off another spectacular escape? Or were there multiple critters patrolling the Great Lakes?

Years later, the Milford Times revived interest when it reported on an object that “resembled a sea serpent but which is believed to be a sea lion off the coast of Benton Harbor, ” (5.11.1901). The reporter thought it might be the notorious pup from Chicago who went missing “three years ago”—altering the animal’s departure date once more.

This pattern repeated in 1903, after the creature was seen on Michigan’s southwestern coast, near St. Joseph. This time it was given a new name —“Big Ben”—and updated backstory. A report in the Clare Sentinel explained how it broke out of a Chicago zoo a mere “three weeks ago” (12.3.1903).

Things quieted down until 1907, when there was much rejoicing in northern Michigan resort towns as reports of a sea lion ‘flap’ flooded the Grand Traverse Bay. A series of articles appearing in the June 25-27 Evening Record recorded an encounter by “Captain Dave” who was rowing across the inlet one evening.

His trip was interrupted by a brown haired animal with “two sharp white tusks protrud[ing] from the mouth” splashing near his skiff. Commenting on this depiction of walrus-like ivories, the Record suggested a species of freshwater walrus could be responsible for the sightings. Adding credence to the walrus theory, an unknown mammal with a “reddish brown color,” pointy head, and sharp tusks was snared that same day in Lake Ann, a small lake 10 miles inland from Grand Traverse Bay.

Another group reportedly got within 50-feet of the animal while it was lounging in the sun, putting it at approximately 6’ in length. Witnesses heard it “bark[ing] like it was a sea lion.” The following day, a fisherman in the bay pulled his nets to find a haul of lonely fish heads missing their bodies—a sign that something strange was feasting on them below the waves. The Record wondered if it might not be the usual suspect—“Big Ben,” formerly of Chicago.

Sea lions were subdued until 1935, when a precocious-pinniped made multiple stops on a tour of Lake Michigan vacation spots. An article printed in the Michigan Alumnus recounted the adventure of an entourage of men determined to solve the “Grand Traverse Bay Monster” mystery (8.10.1935). During their outing, they claimed to snap photographic evidence of the aquatic mammal and decided that it was a seal instead of a sea lion. According to their estimation, the animal likely defected from its home in Chicago during the 1933 World’s Fair.

This grainy 1935 photo allegedly depicts the Grand Traverse Bay “sea lion.” Despite its low quality, the image is still somehow much clearer than most “lake monster” pictures put forth over the years. That same summer, the Leelanau Enterprise reported a “seal or sea lion” seen frolicking around the inlets near Grand Traverse Bay. One Leelanau Peninsula tourist who saw the animal close to shore described it as “very tame” and between 6-7’ long (8.22.1935). The Enterprise had a bead on the case the following summer as well, reporting that a sea lion was spotted in the same area by the crew of a fishing tug (7.23.1936).

Decades later, the Enterprise brought news of a break in the sea lion case when the body of one washed up on shores of Benton Harbor (11.14.1968). The paper pronounced it “the carcass of an honest-to-goodness sea lion” after they received confirmation from the regional conservation office.

Decades of reports about outlaw sea lions roving the Great Lakes either demonstrate the ineptness of Chicago Zoo security, or more likely, they hint at the formation of an urban legend. The familiar trope was repeated and embellished over time, taking the form of a “friend-of-a-friend” tale. While displaced marine animals might be behind some Great Lakes sea serpent sightings, they can’t account for cases involving double-digit-long, reptilian-looking creatures.

Serpent Staying Power

Speaking of colossal-sized cryptids, the 1990s saga of the Lake Michigan Monster is among the largest.

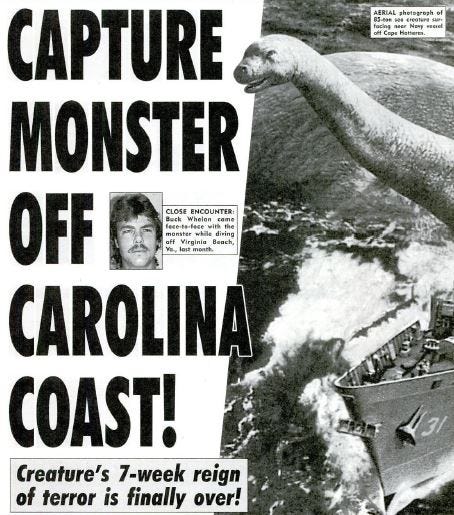

The mostly-satirical, supernatural-themed Weekly World News made a splash with a cover story alleging that the U.S. Navy had successfully trapped a 140’ creature in northern Lake Michigan (11.17.1992). The covert team used a specially- designed steel fishing net to snag the beast and were rumored to be keeping it in a gigantic underwater cage for further study.

Of note was the area of water where WWN claimed the monster was captured: a spot less than 30-miles gigantic underwater cage for further study.

Of note was the area of water where WWN claimed the monster was captured: a spot less than 30-miles from the home of the “Petoskey serpent,” near the confluence of Grand and Little Traverse Bays. Tabloid or not, the location chosen by the article suggests centuries of regional monster stories continue to exert a resounding influence.

As for the fate of the lake’s beleaguered behemoth, WWN ran a follow-up piece announcing that the Navy was releasing the specimen so that it could reunite with its mate (3.2.1993). Commenting on the change of heart, a Pentagon official provided the most un-Pentagon-like statement ever: “The Lake Michigan serpent is as free as the wind.”

The ‘Lake Michigan Monster’ resurfaced years later - proving the beast could transition from fresh to salt water.Its freedom was short-lived. North America was reeling from a ‘cold wave’ in 1994 that hit the Atlantic seaboard with their lowest temperatures in 60 years. Perhaps spurred on by the frigid weather, Lake Michigan’s monster reportedly fled its freshwater habitat for the Atlantic Ocean by navigating the St. Lawrence Seaway (8.30.1994). Remarkably growing 200’ since its last appearance, the serpent now measured 340-feet-long, posing a monumental threat to boats and shipping lanes in its path. Applying the same tactics that worked in ‘92, the Navy snared the monster off the coast of North Carolina before pumping it full of tranquilizers. WWN’s final dispatch claimed that the enormous specimen was under heavy sedation at the naval base in Norfolk, Virginia.

While rarely seen in today’s era of motorboats and watersports, aquatic cryptids were commonly reported throughout history. Did monsters really roam the region in the days before encroaching humans pushed them into deeper water? Or are “sea serpents” simply the byproduct of tarps, tricks, and tourist traps; remnants of a ruse designed to garner press and profits? Even “natural” explanations leave a lot to be desired—lake-going pinnipeds, overgrown fish, and unidentified floating objects don’t fully explain the wide-range of creatures documented by centuries of witnesses.

Ultimately, answers to the mystery might be found in the places explored by folklorists like Richard Dorson during his trek through the Upper Peninsula—those enduring pockets of society, where timeless legends pool and accumulate like the bodies of water that surround them. While the matter of serpents in the Great Lakes remains unsettled, their presence is always lying in wait, floating just beneath the surface of our collective memory banks.