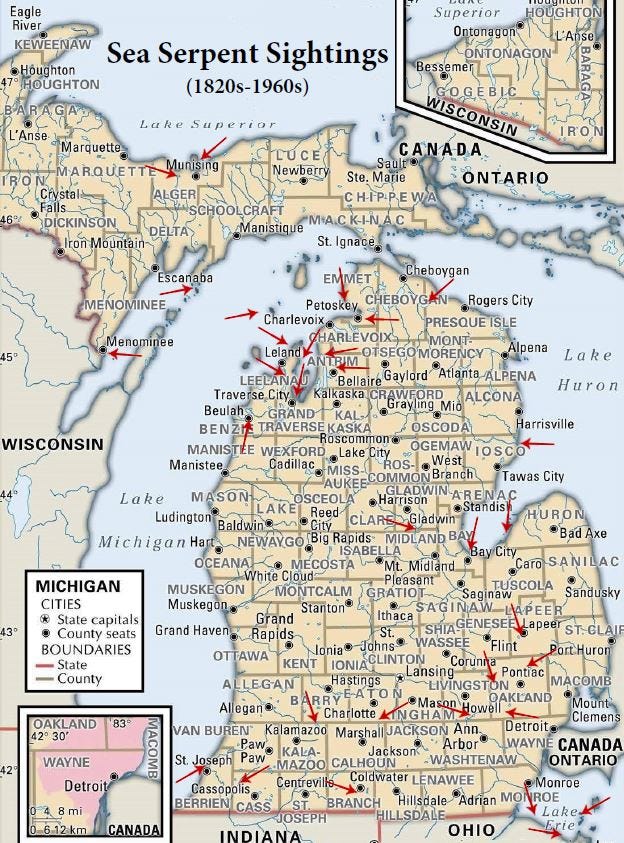

In the mid-1800s, the freshwaters of the Great Lakes were teeming with monsters. Ships from every port brought tales of large, mysterious animals inhabiting the vast blue expanses. Back on shore, the local press eagerly documented hordes of sea serpents and other aquatic cryptids.

While reports grew increasingly novel during the era, these water-dwelling curiosities weren’t exactly new. Legends told by indigenous tribes prove that beasts from the deeps were believed to be rampant before the arrival of European explorers. As the century progressed, both logging and tourism would play crucial roles in the development of regional serpent mythology, but these important historical catalysts don’t account for every strange thing witnessed in the waves.

Logging was a thriving industry throughout the Great Lakes region—Michigan even led the country in lumber production for a stretch in the late 19th century. White pine trees over 60-feet tall were harvested and shipped by train and boat. An errant tree-trunk bobbing in a lake or river could resemble a sea serpent from a distance, but this explanation only fits for a handful of sightings.

These frontier settlements produced more than just serpentine-looking stray lumber—the evolution of the timber trade also meant the progression of railroads and people. By the 1900s, steamers were plying the waters, and miles of new track were being laid to facilitate expansion.

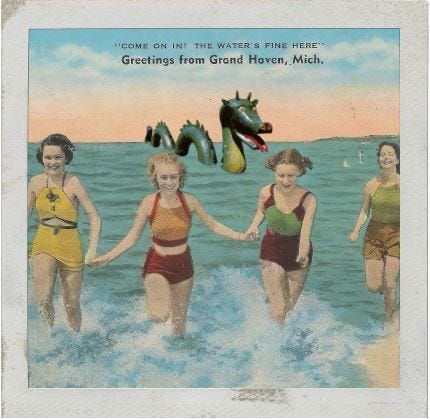

Advances in transportation connected isolated ports and lumber outposts with larger cities. Remote lake towns soon welcomed a steady stream of vacationers seeking solace and respite among the area’s natural beauty. Resort proprietors and business owners understood that an unknown lake monster could bring added attention to their neck of the woods. Instead of hiding the dangers lurking in neighborhood swimming holes, many locals eagerly advertised sea serpent stories.

Still, this motivation doesn’t explain every aquatic anomaly. Water monsters weren’t concentrated in a single area—they trickled across the region, saturating the lore of wide-ranging locales. Some tales originated in places that had no stake in tourism, suggesting that creature reports can’t be easily written off as the invention of imaginative innkeepers trying to line their pockets.

Regardless of their authenticity, the press was complicit in propagating the notion of “inland sea serpents.” In an era when news traveled slowly and follow-up articles were rare, sensationalism was the rule and rarely the exception. Incredible reports featuring strange animals were often published to boost circulation. A typical example is found in a headline from the August 27, 1883 New York Times. It warned readers about the “Sixty Feet of Sea Serpent” prowling Lake Michigan (925’ deep) near Summer Island—a spit of land located just south of the state’s Upper Peninsula. According to the report, people saw a “monster with alligator head” and “three fins along its back.”

Lake Erie—the fourth largest Great Lake with a depth of 212’—trumpeted its own shy goliath in 1887. A pair of fishermen encountered a huge amphibious animal after it became beached on the shoreline near Toledo (Omaha Daily Bee, 5.20.1887). The witnesses claim it was 20-30 feet long and resembled a giant sturgeon (a prehistoric species of fish that can grow upwards of 12’ in length) with arms instead of fins.

Years later, the Gladwin County Record ran an article about a 25’ monster seen in Lake Erie, 45 minutes east of Toledo. Observers described the black-colored beast as having “several large fins or flippers about five feet from the head” (5.27.1892). Another sighting was reported in 1897 off the coast of Sugar Island. The Record described the creature as being barrel-width with a horse-shaped head (8.6.1897).

These early tales combined with other confrontations around Ohio to establish the legend of a local cryptid dubbed “Bessie.” Cryptozoologist Ron Schaffner did exhaustive research on Bessie through his now-dormant magazine, Creature Chronicles. His analysis revealed that the sightings in Lake Erie are consistent with a massive sturgeon. Adding credence to Schaffner’s explanation was the May 2021 catch of a 7-foot, 100-year-old lake sturgeon in the nearby Detroit River.

Lake Sturgeon can grow to double-digit length, creating an imposing shape as they move through the water. Before long, sea serpents were wiggling their way into smaller interior lakes. Throughout the summer of 1887, word spread that Lake Michigan’s monster was taking day trips into the shallow bodies of water sprinkled along Michigan’s northwest coast. Due to the complex network of tributaries intersecting the state, the possibility that something could find its way inland from one of the “big lakes” wasn’t far-fetched. The prospect didn’t amuse one fed-up Bellaire resident who purchased a load of dynamite to detonate in serpent-infested Intermediate Lake: “When they go off, the monster will want to go too,” (Diamond Drill 9.10.1887).

A report in the Weekly Expositor announced the presence of a 30-footer in eastern Michigan’s Walled Lake—a surprising choice considering it’s only the fourth largest lake in its county, with a depth of 50’ (6.19.1884). Sadly, Novi’s Evening News drained the tank on the serpent theory before it could mature, explaining that the monster was discovered to be “a huge log of wavy, irregular shape” (6.20.1884).

Misidentified logs, branches, and trunks—tree parts in general—have generated a fair-share of ‘serpent’ sightings throughout history. Yet maybe there was something more substantial behind the Walled Lake encounters, as years later the creature was back in action and back in the papers. None of it impressed the editor at the Milford Times, who quipped that “the quality of Walled Lake whiskey may be inferred” by the frequency of monster reports in the area (6.12.1909).

On September 9th, 1886 the Newberry News alerted readers about a creature dwelling in the small, landlocked Narrow Lake—a puddle 10 miles south of Charlotte in south central Michigan. The beast was shaped like a “stovepipe” with the head of a snake, and able to raise itself 10’ out of the water. The town was frightened to the point of action, and a contingent of concerned residents conscripted a search party to investigate. The Isabella County Enterprise’s account explained that the group heard the “sea monster” hissing like a snake, but its elusiveness made it difficult to secure a positive identification (9.10.1886).

Despite charges of alcohol-fueled witnesses and a general skepticism toward the idea, freshwater serpents coiled themselves around the public’s consciousness. In 1886, their reality was well-enough established that circus-owner and showman P.T. Barnum dangled $20,000 in front of the first person that could furnish him with one of the creature’s hides (Grand Traverse Herald, 9.16.1886).

Around that same time, a wealth of sea serpent reports popped up in Torch Lake—the second largest interior body of water in Michigan. Situated in the northwestern portion of the state, the reservoir connects to a string of rivers and lakes that empty into Lake Michigan. It’s possible that a large aquatic creature could have traveled from the larger lake, through the chain of waterways, and into Torch Lake; however, a piece by the Milford Times put the speculation to rest when it revealed that the fearsome cryptid was the result of a local prank. After shooting “several pounds of lead” at the supposed serpent, a hunting party discovered that their quarry was only a contraption made from “canvas, leather and sawdust manipulated by ropes from the shore” (7.30.1892). Similar hoaxes would rear their heads as the frenzy over sea creatures gained momentum in the waning years of the 19th century.

Michigan’s east side was lake monster territory as well. A summary printed in the Newberry News claimed that a 25-foot colossus was winding its way through the Saginaw River, presumably headed for the open waters of Lake Huron (725’ deep). Witnesses claimed that the beast was able to hold its head well above water, a pose that brings to mind iconic images of the Loch Ness Monster and other “long-necked” cryptids (8.26.1892).

Many newspapers covered an incident that occurred near Lake Nepessing, located in the state’s ‘thumb.’ The inland lake has an average depth of only 10’, with no obvious places for a 30-foot sea serpent to hide. If the True Northerner’s account can be believed, perhaps the key to the creature’s survival was its ability to adapt. The paper claimed that the barrel-headed beast “chased” two men across 10 acres of dry land (6.24.1891).

A dispatch in the Isabella County Enterprise warned residents that a “monster sea serpent” was spotted in the Coldwater River (7.28.1893). The tributary is part of a larger watershed that snakes its way over 70 miles before reaching the open waters of Lake Michigan, creating a possible inland route for a determined serpent.

By 1895, serpent sagas were pouring into newsrooms from Menominee to Au Sable. An article appearing in the Pontiac Daily Gazette reported four different sightings of a “sea serpent, having the appearance of a sea lion” in the waters of Lake Huron near Saginaw Bay (8.17.1895). The Detroit News ran a story about a woman who lost her swimsuit to a “sea serpent that looke [sic] like a sea lion and was five feet long.” The Grand Traverse Herald added color to the story, surmising that the creature must be the same one that frequented the waters on the west side of the state (8.22.1895). Their article placed the “fair maiden” with the stolen suit at Wenona Beach—a popular lakeside amusement park once known as “the ‘Coney Island’ of the Lakes.” The Herald playfully asserted that the serpent was so stunned by the woman’s beauty that he attempted to “induce her to go along with him and be a mermaid bold.” Luckily for the would-be victim, her suit gave in before she did, and the serpent retreated without his prize.

What can we make of these early lake monster accounts? Are they nothing more than fodder drummed up by locals with skin in the hospitality game? Or do they hint at the existence of something real? There certainly is plenty of room for a large, undiscovered animal to hide in the depths of the Great Lakes and its surrounding bodies of water. The abyssal recesses that became the lakes’ basins were gouged into the landscape some 10,000-14,000 years ago by the movement of continent-spanning glaciers. As these ice sheets melted, their run-off collected in the massive footprints they left behind, creating reservoirs of impressive depths.

Could an isolated population of prehistoric aquatic animals have quietly survived or adapted to their new habitat after the glaciers receded? The intertwined waters of the Great Lakes ultimately flow into the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence Seaway, providing a pathway for an ocean-dwelling leviathan to access the “Inland Seas” of the American Midwest.

Many researchers tout the existence of specific “Monster Latitudes”—areas of the globe where the bulk of sightings originate. In The Field Guide to Lake Monsters, Sea Serpents, and Other Mystery Denizens of the Deep (2003), cryptozoologist Loren Coleman and author on anomalies Patrick Huyghe summarize the characteristics of these regions, noting the similarities in ecosystems, the presence of dense forests, and an abundance of coldwater lakes. Famous cryptid habitats like Loch Ness and Lake Champlain fall within these geographic boundaries—and so do the Great Lakes.

Perhaps owing to this ideal monster-climate, the creatures proliferated in regional watering holes. In 1894, the hamlet of Orion, located 25 miles north of Detroit, promoted the arrival of a sea serpent in its eponymous body of water. The timing was convenient for the budding resort town, as newly built railroad tracks created an influx of vacationers eager to visit the “Paris of Detroit.” Rumors of a lake monster—authentic or not—added an element of danger and gave tourists something to look for while riding the wooden roller coaster and other amusements littering the shore.

Orionites who witnessed the serpent (or dragon, as it was often known) described it to the Pontiac Gazette as “having the head of a dog, a body as big as a stove pipe, covered with yellow spots and is about 40 feet long” (8.10.1894). Further stoking the legend, the paper declared that the creature had an appetite for “swallowing all the bad little boys.” By August 18, the Milford Times reported that the townsfolk had amassed an armed posse with orders to capture or kill the beast, and according to the True Northerner, they got a little help from a protective aunt (8.24.1894). Mrs. Brown was allegedly out for a row with her nieces on Lake Orion when the serpent came calling. The quick-thinking Brown whacked the uninvited guest with a branch, causing it to “emit a horrible roar” and kick up a large wave as it departed. By her estimation, the monster was close to 80’ long (hard to believe, considering the deepest part of the lake is 80’).

The Detroit Evening News was skeptical of Orion’s “sea devil,” blaming the rash of sightings on “lurid imagination and very bad whisky.” The same went for the editor of the Pontiac Gazette, who figured that if visions of serpents continued in Orion, “the Asylum for the insane will have to be enlarged” (9.7.1894).

The little village of Orion continued to feature its well-documented serpent in the summer of 1895. A series of articles by the Pontiac Daily Gazette joked about letting the beast roam freely on the grass during an upcoming meeting of the Michigan Academy of Science. The Gazette reporter wondered if the scientists might find a way to “size up the Orion sea serpent” in between surveys of flora and fauna.

Citizens were also concerned about how the landlocked lake-dweller would fare over the course of a frigid Michigan winter, but a June 12th bulletin by the Gazette “assured he has wintered all right.” Their report provided a narrative from two women who were out on the lake when the serpent materialized next to their vessel. Their screams startled the creature, and as quickly as he emerged, he was gone. In the meantime, the boaters made haste for the relative safety of the shore.

By September, the diligent staff at the Gazette had unwound the Orion Lake Serpent mystery. A local resident stumbled upon the brute as it lay motionless in the late summer sun. After further inspection, he concluded that its lethargy was caused by its inanimate nature—the object was “hand made and manufactured by one of the bright boys of Orion.” Constructed from coiled wire and canvas embellished with brown paint, the device was apparently attached to a wire that controlled the ‘snake’s’ movement. The nearby Milford Times cheered the serpent’s subjugation, assuring locals that it was safe to go back in the water. The monster would “no longer strike terror to the hearts of dwellers and resorters at charming Orion Lake” (9.21.1895).

Even though fabled the beast was reportedly vanquished, its legacy lingers in the area—the local high school adopted a “dragon” as their mascot.

Great article! I'm wondering if you could direct me to some references regarding regular sensationalism in newspapers during the period. I hear this stated a lot, but have been unable to locate any scholarly information discussing this in detail. Would be a big help. Thanks