The Devil in Disguise (Part 1 of 2)

On the cusp of the 20th century, the Devil was Nothing, Nowhere, Never at All ... or was he? Here's a "just in time" seasonal selection from The Observer.

On August 11, 1898, New York City policeman Henry C. Hawley ended his life in a most disturbing manner.

On his last day alive, the 29-year-old father of two reported for duty as expected. Fellow patrolmen said he acted normally and displayed no outward signs of distress. During a routine break from his post at the West Thirtieth Street Station, Hawley made his way to the small Sixth Avenue apartment he shared with his wife, daughters, and mother. Once inside, he barricaded the door with a metal cot and proceeded to murder all four members of his family before turning the pistol on himself.

While most newspapers blamed the savagery on Hawley’s rumored alcohol addiction, a devilish discovery made by detectives on the scene put the killer’s motive in question. Tucked inside his pocket was a statue of Satan.

Acquaintances later told the New York Journal that the officer was completely entranced by his miniature red idol. Decorated with “horns, cloven feet, fiery tail, malicious face and other characteristics of the spirit of evil,” the object’s allure influenced his every move—the papers called it “his guiding star.” A woman Hawley had been sleeping with told police that he frequently prayed to the statue in her presence, claiming it provided him a form of supernatural protection. The figurine’s existence was cited by authorities as evidence that the disgraced lawman had sold his soul to a secret society of Parisian “Devil Worshippers.”1

History recognizes scattered instances of devil worship in the late 19th century, but the general consensus is that these occurrences were relatively isolated and not indicative of a wider trend. Beyond sensationalized stories, concrete evidence of malevolent cults was sparse. As a result, the public wrote-off such lurid tales as fantasy, with one New York outlet confidently declaring in 1901 that “in the United States, there is no satanism.”2

However, a careful examination of nefarious events reported during the time period makes us wonder: Should people have been freaking out more? Why didn’t they? The occult implications of Officer Hawley’s case alone should’ve set off fire-alarms in the press.

Instead of massive news coverage, the story disappeared from the headlines with minimal fanfare. There was no follow-up coverage or investigation into the source of the wicked sculpture found in his possession.

Something sinister played out inside Hawley’s cramped fourth-floor apartment, and the public indifference was perplexing. Why didn’t this potential threat inspire a “Satanic Panic” similar to the one that transpired 100 years later, in the 1980s and 1990s?

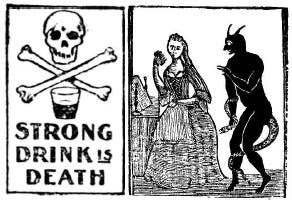

An analysis of late 19th century society reveals a key factor behind their general lack of concern toward Satanism: people of the Progressive Era were preoccupied with civic and social reforms. Many of these moral crusaders considered alcohol to be one of the nation’s gravest sins. Keeping with the times, Officer Hawley’s actions were roundly blamed on the liquid devil—not the spiritual one.

In a scene tailor-made for Team Temperance, the officers who responded to Hawley’s blood-soaked residence made it inside just in time to hear his dying wife squeak out her last words: “Drink caused all this.”

In another stroke of luck for the anti-boozers, Hawley’s mother apparently recovered long enough to corroborate her daughter-in-law’s statement, telling police that her son’s mind was “deranged from drinking whisky.”3

The official rag of the Minnesota Prohibitionist Committee wasted no time in exploiting the tragedy for its own agenda, citing Hawley’s crime as an example of the violence taking place in a country with loose libation laws.4

The article conveniently failed to mention any connections to devil worship.

While prohibitionists clutched their pearls over Hawley’s drinking habits, accounts of his dark allegiance casts shadows of doubt over true his motivations. Despite clear warning signs, the Progressive Era’s focus on social issues meant that society wasn’t freaking out over the thought of a cop in a devil cult.

The public cared less about accusations of Satanism than they did about the horrors of Satan’s cough syrup.

Consequently, New York’s “Policeman Devil-Worshipper” was dismissed as just another poor soul possessed by the spirits hiding at the bottom of a liquor bottle.

A Satanic Scam

There’s another key reason why people weren’t overly-concerned about practitioners of the dark arts in the late 19th century—they’d just fallen victim to a decade-long literary hoax involving accusations of rampant devil worship.

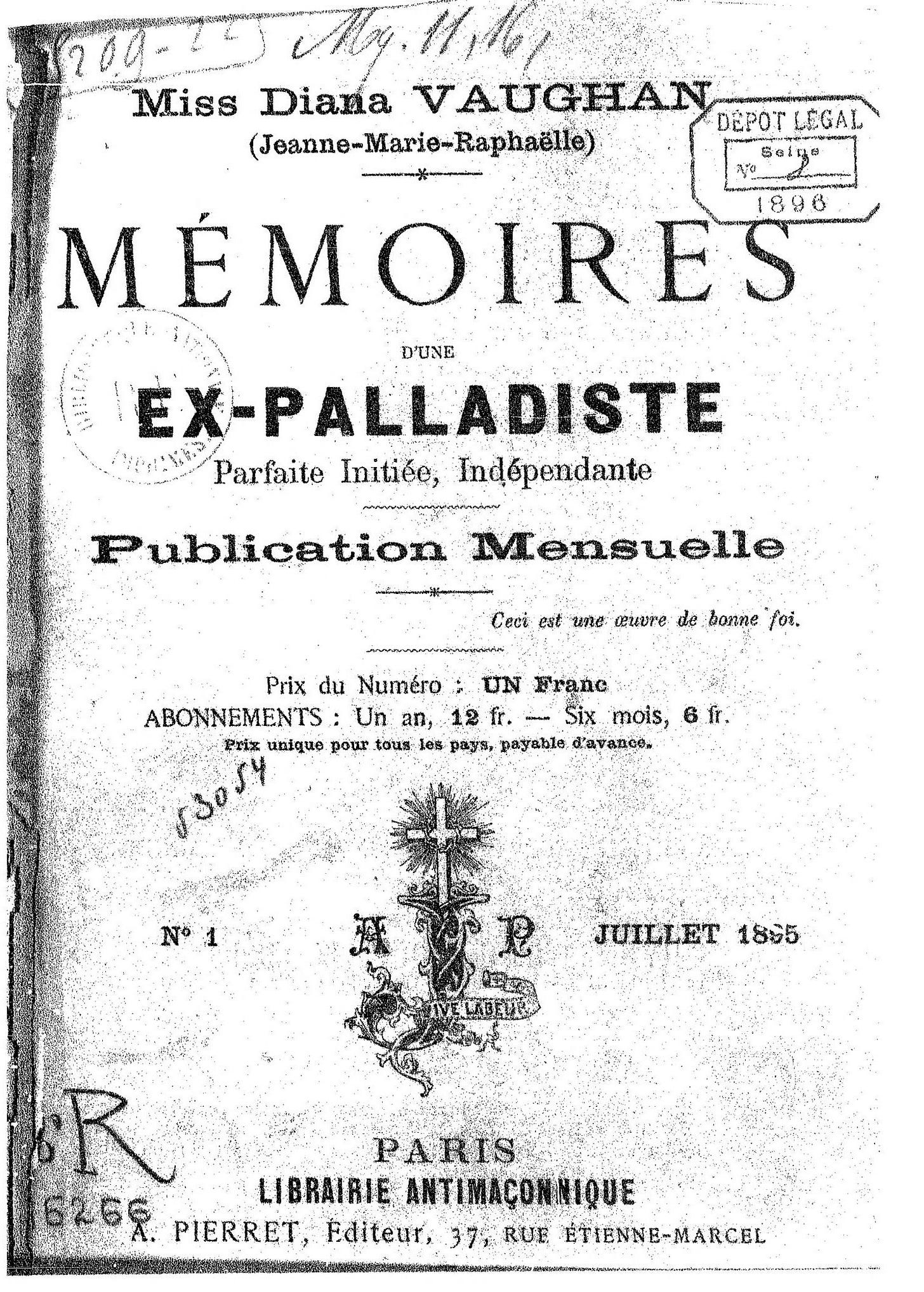

Writing under various nom de plumes between 1885-1897, French satirist Gabriel Jogand-Pagès released a steady stream of “non-fiction” that ostensibly exposed the inner rites and practices of contemporary Satanism.

The most infamous creation of his 12-year run was a former Freemason, turned Luciferian, turned Catholic, Diana Vaughn.

Known by colorful nicknames like “the devil’s bride,” and “great grandmother of the antichrist,”5 Diana’s fictitious reign as the high priestess over a band of Masonic Satan worshipers was detailed by Jogand-Pagès in Memoirs of an Ex-Palladist.

The outlandish tale describes how the imaginary “Diana” was initiated into the cult at a young age before eventually promising herself to the lustful demon, Asmodeus. According to her exposé, this kind of conduct was typical, and numerous prominent Masons frequently engaged with the Devil from their headquarters in South Carolina.

The tract’s gruesome descriptions of demonic orgies and child sacrifices pushed the boundaries of believability, but apparently didn’t break them. Even the author was surprised by the ready acceptance of his wacky material:

“I sometimes said to myself: ‘Hold on; you are going too far;’ but I didn’t … I thought I would kill myself laughing at some of the things proposed, but everything went.”6

Despite their fantastic nature, many regarded Jogand-Pagès’ accounts as true, and some of the loftiest members of the Vatican were duped for a dozen years. Rosary Magazine bought the story hook, line, and sinker, telling readers that Diana Vaughn “had truly become the apostle of Lucifer.”7

Part 2 here

New York Journal and Advertiser, Aug. 12, 1898.

Johnstown Daily Republican, Jan. 5, 1901.

New York Times, Aug. 12, 1898.

The Backbone, Aug. 1, 1898.

The Indianapolis Journal, Sept. 29, 1901.

Ibid

Rosary Magazine, Vol. 9, 1896.

“The tract’s gruesome descriptions of demonic orgies and child sacrifices pushed the boundaries of believability, but apparently didn’t break them. Even the author was surprised by the ready acceptance of his wacky material:”

Fictionalization Satanism, and no on will be it. During that era Houdini spent much of his time debunking mediums, so the entire industry of seeking your higher-self and nurturing your 6th sense became something you poo-pooed and laughed about.

Fortunately today there is a revival is spiritualism, and authors like Demi Pietchell who publishes The Starfire Code is setting examples that spiritism is used to increase the positive frequency of earth and beyond. We need this to counter the Satanic energies of people like P Diddy. And we need to find that within ourselves, and become like an angel of good light connected to our divine source. Thank you, I look forward to reading Part 2! BTW Demi wrote an in-depth essay about the influence of Satanism or demonic forces attached to early immigrants from Europe. I’ll look for it and share your article with her link. Thank you !