Recap: The Philadelphia Experiment (PE) is a fantastical tale about a disappearing Navy escort ship and crew. While the truth behind the matter is hotly debated, there are some interesting historical precursors that might’ve played a role in the PE’s development. In Part 1 we examined Thomas Edison’s early tests with invisible boats and their crossover with the PE. In Part 2 we dug into the story of the ‘SS Mohican’ and its run-in with a supernatural phenomenon. In the story’s conclusion we discuss Colonel W.R. King’s super-magnet-gun and its relationship to the concepts associated with the PE.

King of the Hill

Another little-known forerunner to the Philadelphia Experiment (PE) that is rarely (if ever) highlighted involves similar tropes: the construction of a unique military weapon, tests with directed energy, and an east coast naval base.

Lieutenant Col. W.R. King was a West Point graduate who made a name for himself during the Civil War. An accomplished member of the U.S. Corps of Engineers, King also possessed a unique flair for weapons development.

In 1887 he did a stint at Willets Point—a naval outpost located less than 50 miles from where Thomas Edison would later conduct his invisibility research in the Long Island Sound.

In addition to running an engineering school on the premises, Col. King spent his days thinking up ways to defend New York from a naval attack and testing torpedoes and high explosives in the harbor.

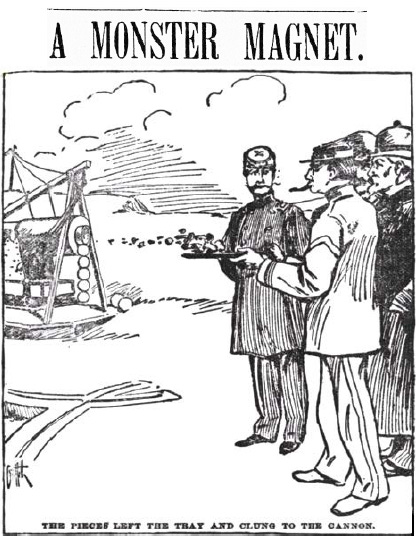

He also managed to concoct one of the strongest magnets in the world at the time. The imposing device consisted of two cannons strapped together with miles of electrified submarine wire. It measured 18-feet long, 10-feet high, and weighed-in at more than 20 tons.

Once the electromagnet was activated, metal objects in the area were quickly pulled in the cannon’s direction.

King tested the limits of its strength by stacking heavy pieces of metal end-to-end to see how much the magnet could hold at one time. Different reports claimed that it could suspend a chain of railroad spikes in a horizontal line measuring four feet long. Others alleged it could hold anywhere from three to five iron cannonballs weighing 350 lbs. apiece off the ground.

The apparatus also had the power to stop time—or at least watches—as the mighty magnet was able to jostle the delicate inner workings of the era’s timepieces.

As might be expected when dealing with a formidable- looking contraption like King’s magnetic cannon, conjecture ran wild. The Bismarck Weekly Tribune (12.7.1894) offered ideas for how it could be used on the battlefield, alleging it was strong enough to confuse the compasses on enemy ships up to six-miles away—a claim denied by King. The Tribune also thought it might be useful in land warfare if it were capable of tearing metal guns from the hands of advancing soldiers.

Riffing on these ideas, Columbia professor W. Hallock suggested “planting a line of these great magnets across the entrance to a harbor” as a means of preventing opposing ships from nearing important cities. A steel vessel would trigger the sunken devices to rise to the surface and attach themselves to a passing hull or propeller.

Despite these grand proposals, King’s intimidating gadget was primarily for show: “It demonstrated nothing new and it was of no practical purpose.” The New York Sun (6.1.1898) presciently revealed how despite this mundane reality, the legendary machine took on a life of its own:

“The yellow journal of the day, however, described this magnet as powerful enough to draw iron bolts out of passing ships when the electrical current was on full force… The story of the magnet made the rounds of the European papers, gaining strength as it travelled. It finally became a terrible instrument of destruction devised by Yankee ingenuity, and according to one account of it which appeared in a French paper, its power was so great that if a naval vessel approached within six miles of it her guns would be torn from their fastenings and sent rushing toward the magnet.”

In a fitting gesture, after King’s death in 1898, the federal government gave his name to the mightiest steel towboat in their fleet.

What can we make of these past incidents and their relationship to the Philadelphia Experiment? The PE has captured the imaginations of many, but it’s important to separate fact from fiction—or at least understand how one influences the other. The PE exaggerated historical antecedents like Edison’s marine camouflage, the Mohican’s mysterious magnetic cloud, and King’s electro-cannon into unrecognizable echoes of the truth—an urban myth that stretched fact into fodder for folklore.

While there is no concrete evidence to support the wilder claims of the PE, there are historical precedents for some of the concepts and technologies involved. The mythology surrounding the PE serves as a reminder of the power of legends and how they can persist and evolve over time. Examining the connection between tall tales and reality can provide insights into how myths are created and perpetuated in popular culture.

This has been a fascinating story to follow.