Strange Ships at Sea, Part 1

Edison's electromagnetic experiments? We analyze the historical precedents that inspired the infamous "Philadelphia Experiment."

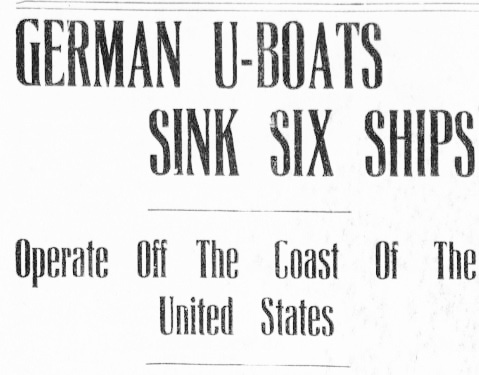

There are well-worn rumors about strange experiments that took place in a lonely Philadelphia shipyard—experiments that tampered with the very essence of time and space. Under the auspices of saving American lives at sea during World War II, a conglomerate of the country’s brightest minds met at a secret research facility on the east coast in 1943. Their goal was to create a vessel undetectable to the German U-boats that were having a field day with military and merchant ships sailing across the Atlantic Ocean. Legend holds that the scientists were intent on more than just camouflage—they became obsessed with creating a completely invisible ship.

To achieve their goal, a series of tests were designed that included unprecedented levels of electromagnetic energy aimed at a Navy escort and her crew.

The results were horrendous.

After the switch was flipped, a green fog enveloped the vessel, which made the craft disappear and/or teleport to another location down the coast. Most of the Navy’s unwitting guinea pigs became physically sick and mentally rattled. Unsettling whispers made the rounds about sailors getting stuck within the ship’s walls and hull like Han Solo in carbonite. A number of men even vanished into thin air, lost in limbo for eternity. Some researchers attribute these effects to the opening of an interdimensional vortex, while others allege elements of time travel were involved—but most versions agree that unnatural forces were harnessed in Philadelphia’s harbor that summer.

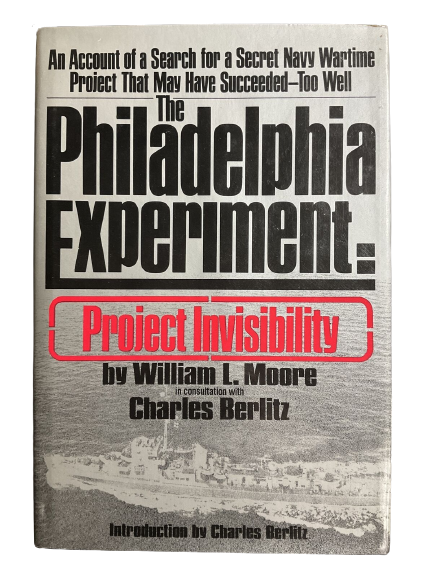

First hinted at in 1955 by ufologist Morris K. Jessup, “The Philadelphia Experiment” (PE) was further popularized in 1979 by William Moore and Charles Berlitz in book of the same name.

The story has since solidified into a well-known pseudo-factual urban legend detailing strangeness on the high seas. The lurid and fantastical account combining electromagnetic forces, an invisible ship, and tortured sailors incorporates actual people and places while drawing details from obscure historical incidents. Many of the PE’s precedents have been documented elsewhere—we highlight these along with some lesser-known examples in the pages ahead.

Where’s Tom?

Inspiration for an invisible ship like the one featured in the PE can be found as far back as 1917. Woodrow Wilson was president, the country had just entered the First World War, and light bulb-guy Thomas Edison was hot on the trail of a solution to the German submarine problem (the same problem cited as motivation for the PE).

According to NPS.gov, the Navy gave Edison his own floating science lab in hopes of solving the issue:

“The USS Sachem was a private yacht outfitted by the U.S. Navy for Edison and his employees. From August to October in 1917, Edison conducted experiments aimed at the camouflaging of ships and torpedo detection.”

Edison also pushed for the creation of a full-time naval research facility consisting of “a laboratory on the water where a ship could be docked, nearby a large city.” Minutes from an August 4th, 1917 Naval Consulting Board meeting clarify Edison’s mission, promising he would produce tactics “for rendering ships less visible.”

Secret naval research regarding invisible boats? Sounds pretty Philadelphia- Experimenty to us.

Edison worked with the Navy to develop various modalities for evading visual detection. According to his notebooks, he spent months drifting in the Long Island Sound testing different forms of camouflage that would conceal his boat from view. One disguise involved ⅛ inch cords of hemp rope painted black and hung over the vessel’s side like a Ghillie suit.

The famous inventor’s hush-hush projects during this time were ripe for speculation by a press with little care for the reliability of sources. Their dubious assertions helped lay the foundation for one of the PE’s central themes involving the U.S. Navy and disappearing boats.

The papers of the day made hay out of the inventor’s frequent absences from his New Jersey lab. Reports insinuated his participation in top secret military experiments with the possibility that he had discovered a way to make physical objects imperceptible to the human eye. Dispatches quickly spread out across the wires, fanning the flames of hearsay and conjecture. The October 18, 1917 edition of The Washington Times reported that the “wizard of electricity” was conspicuously missing from his usual haunts and wondered whether Edison had “made himself invisible on an invisible ship.” The article suspected that a larger conspiracy was likely afoot: “there is more to the invisible ship than has been told of it.”

Oregon’s Evening Herald (10.11.1917) ran a piece about Edison’s undertaking which hinted at additional covert projects in the works. Short on details, the article explained that these “other measures [were] being kept quiet as far as possible.”

A blurb from the El Paso Herald (10.17.1917) tread further into the fringe than most outlets. Underneath a front-page headline exclaiming, “Edison Invents Ship That Can’t Be Seen,” the paper claimed that the renowned innovator had devised a way to make a ship undetectable—and it wasn’t the result of mere physical camouflage. The Herald alleged that Edison’s vanishing vessel was the product of “some unique discovery of the electrical wizard.” Exactly what sort of hi-tech sorcery was being practiced was left up to the readers’ imaginations.

Idaho’s Emmet Index (11.1.1917) anticipated their subscribers’ skeptical reactions with a pithy review of Edison’s invisible boat: “It sounds like a cock and bull story.”

Word of Edison’s concealed craft spread as far as Alaska where the local Daily Progressive-Miner (10.25.1917) soberly relayed the details to a captive audience. The paper outlined some of the mechanical modifications that enabled Edison’s ship to drop its mast and lower its funnel while burning smokeless coal. These fittings combined with specific exterior paint made it tricky to spot the boat on the horizon.

In November, The Prescott Daily News (11.19.1917) reported that Edison’s creation wasn’t quite ready for primetime. Navy officials’ awkwardly confessed that “they [had] not yet evolved the invisible merchant ship.” Progress was steady, and headway had been made with respect to reducing a vessel’s profile, but American camouflage creators—aka “decorators”—were still a long way off from invoking true invisibility.

Edison wasn’t the first to tinker with visual deception on the water. In the late 1880s various inventors announced patents for invisible boats. An instance was noted in the Daily Morning Astorian (11.24.1885) about “an invisible boat for water-fowl hunters.” A year later Wisconsin’s Watertown Republican (2.3.1886) informed readers about a sneaky ship that was cut down in size and covered in mirrors to reflect the waterline and mask the hull from unsuspecting ducks.

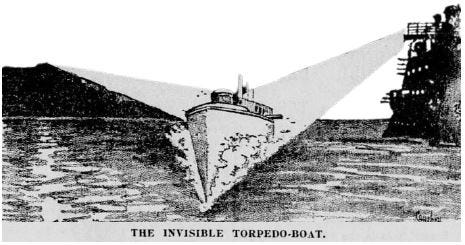

Another development came in 1897 when the French Navy unlocked the secret of an “invisible paint” that made ships nearly impossible to see at night.

According to The San Francisco Call (8.28.1897), this “most mysterious but most potent agent” was secretly applied to a French torpedo boat during a routine training exercise. Its mission was to infiltrate a harbor guarded by “the most powerful men-of-war in the French service” without being caught. If the reports are to be believed, though the craft was lit up “again and again by the glaring lights of vessel after vessel,” it was never identified by the other team’s opposing patrol. The invisible paint was deemed a success.

The Last of the Mohican

While Edison spent most of 1917 bobbing off the coast of New York in the USS Sachem, the year was also significant for another ship credited with inspiring aspects of the PE mythos.

In 1917, the Italian cargo ship Clio went out of service due to a wreck it suffered while making a run from Virginia to Italy. Before it was the Clio (Italian for “glory”), the vessel was chartered by the British under the name SS Mohican. The 2,728-ton steamer was built in 1892 by Joseph F. Thompson & Sons—one of the largest shipbuilders in England—and sailed regularly out of Bristol and Swansea, destined for New York or Baltimore.

The Mohican was a real ship, but it became enmeshed in a dubious encounter with an aggressive electromagnetic cloud. This incredible incident was planted in the press, giving the tale a chance to survive for decades to become one of the Philadelphia Experiment’s most compelling precursors.