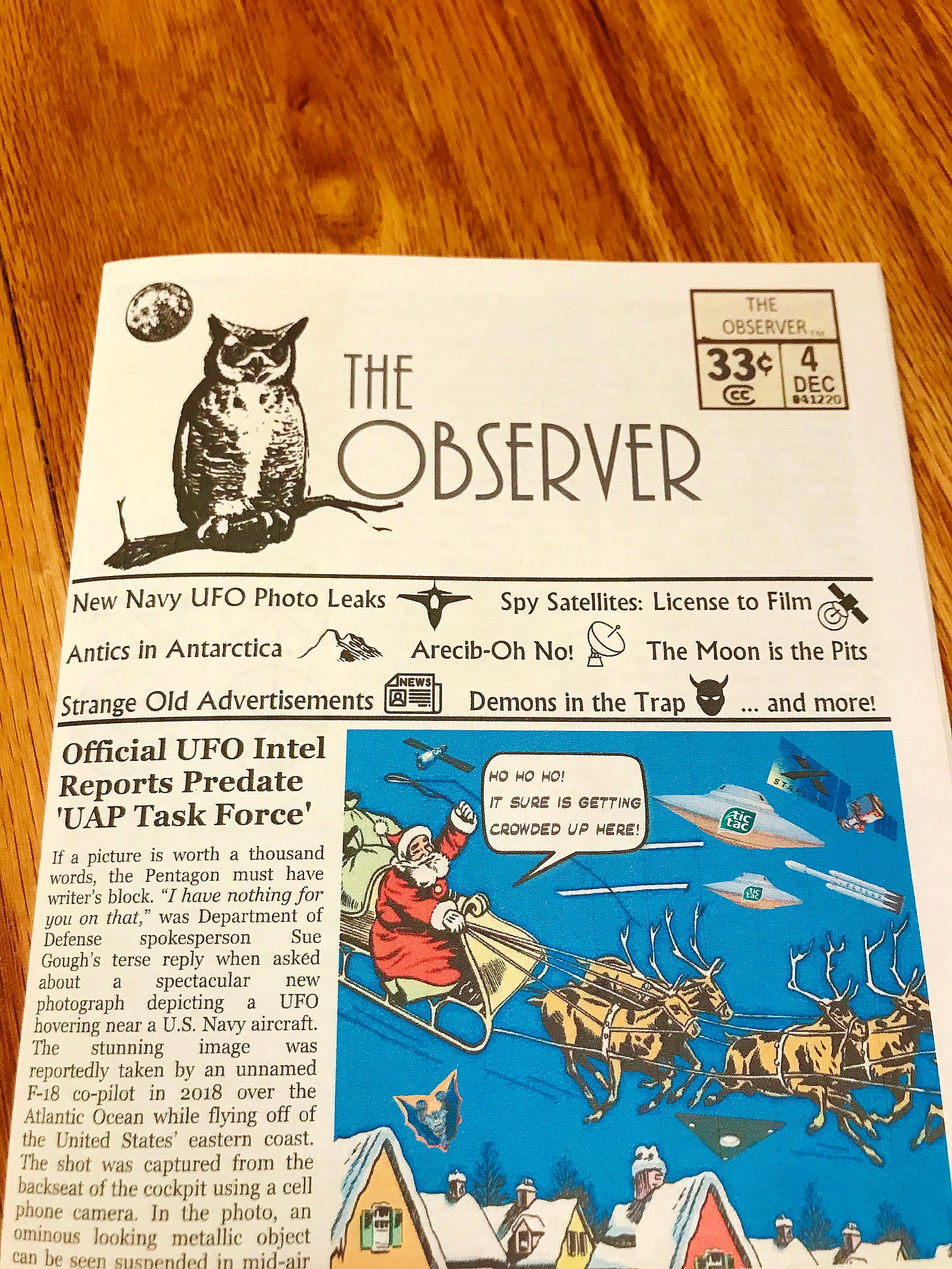

Click here for Low Temps, High Strangeness Part 1

Maps that Match

Even before the body of land known as Antarctica was officially “discovered,” early academics reasoned that something like it must exist. Belief in a natural order and balance was widely held, and tales about a Terra Australis Incognita (“unknown land of the South”) had been in circulation since the second century. In a nod to “as-above-so-below,” ancient scholars figured that the land around the arctic north must also be equally represented at the Antarctic southern pole. While this suspected “hidden land” accounts for many ancient maps appearing to display Antarctica, a few enigmatic examples aren’t as easily brushed aside.

Contemporary historians routinely explain away these interpretations as a gross (and purposeful) misrepresentation of the primary material. According to the official timeline, it wasn’t until James Cook’s voyages to the iceberg-filled latitudes below New Zealand and Australia in the 1770s that the scope of the emerging continent came into view for cartographers. Likewise, according to accepted chronology, mankind didn’t step foot on the windswept badlands until 1821. This official narrative begins to unravel with the analysis of a trove of inexplicable world maps, published centuries prior to 1770, clearly and accurately depicting a landmass located at the southern pole.

Piri Reis Map (1513) Compiled by Turkish admiral Piri Reis from a slew of earlier sources (including some from Christopher Columbus’ collection), this antique map is touted for its depiction of a large landmass beneath South America that some investigators argue is an ice-free portrayal of Antarctica. Cited heavily by revisionist historians, the document was given credence by military experts when it was found to sync up with a wealth of Antarctica’s subglacial features. According to M.I. Walters from the Naval Hydrographic Office: “We have taken the old charts and the new charts that the Hydrographic Office produces today and made comparisons … we have found them to be in astounding agreement.”

Charles Hapgood relied heavily on ancient maps like Piri Reis’ to help prove his thesis about crustal displacement and the movement of the Earth’s landmasses. He brought the 1513 illustration to the attention of Air Force cartographers to validate the geographic similarities between Piri Reis’ drawing and the actual coastline. He received a decidedly no-nonsense military response from Lt. Colonel Harold Ohlmeyer, agreeing that Hapgood’s, “claim that the lower part of the map portrays the Princess Martha coast of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica, and the Palmer Peninsula is ... the most logical and in all probability the correct interpretation of the map.” Even the good Lieutenant was confused by these findings, but he clearly knew when to avoid speculation: “The ice cap in this region is now about a mile thick. We have no idea how the data on this map can be reconciled with the supposed state of geographic knowledge in 1513.”

Critics contend that the Piri Reis map is merely showing a warped, horizontal view of the southernmost tip of South America. They cite the apparent presence of tropical plants and animals in the region alleged to be Antarctica as proof that Piri wasn’t depicting the desolate polar continent. Consequently, this is the same visual “proof” that revisionists use to suggest that Piri Reis’ sources predated a glacier-filled Antarctica.

Oronce Finé Map (1531) This ornately illustrated map included lines of longitude, which were valuable to Charles Hapgood when attempting to determine the degree to which the continents might have moved during the Earth’s last pole shift.

The French originator of this map also included a surprising amount of geographic detail, showing the locations of coastal mountains and rivers of a pre-ice continent at the southern pole.

Believing it another example of an Antarctic map produced by unknown ancient mariners, Hapgood requested an analysis by experts in the field. Critics blasted Hapgood’s interpretations of Finé's map and its relation to Antarctica, claiming that there were far more differences between the terrain and coastline than there were similarities. They forget to mention that this accusation is also true for just about every 16th century map of well-known and undisputed locales. Mapmakers were limited by the technology of their era and many reproductions only bear an amusing resemblance to how the land actually looks. Despite enduring ridicule, the correlating topographical sections between the two maps were enough to impress Captain Lorenzo Burroughs, a Chief Cartographer with the U.S. Air Force: “[T]he accuracy of the cartographic features shown in the Oronteus Fineaus [sic] Map (1531) suggests, beyond a doubt, that it also was compiled from accurate source maps of Antarctica at a time when the land mass and inland waterways of the continent were relatively free of ice.”

These “accurate source maps” must have predated Finé’s creation by millennia if they indeed depict an icecap-less coastline. They also strongly suggest that a long forgotten, seafaring civilization had knowledge of an habitable Antarctic continent at some point in the distant past.

Buache Map (1739) Another work of French cartography, often upheld by fringe historians as evidence of early Antarctic explorers, was assembled by Philippe Buache in the early 18th century. His map was unique because it accurately presented the continent as separate landmasses. This detail of its subglacial topography was not confirmed until the 20th century. While a few icebergs are noted on the document, so are multiple coastal mountain ranges, along with a noticeable absence of interior icepack or glacial cover. These details have provided justification for researchers who believe that Antarctica had a much milder climate when it was mapped in prehistory by some unknown ancient culture.

Skeptics highlight the fact that the map’s author embedded clues indicating the southern continent he drew is only a conjecture based on his geographic theories.

How do these “out-of-place” maps accurately recreate a coastline that was heartily submerged under ice when they were created? Theorists speculate that the original maps many of these cartographers consulted came from an even more ancient era in human history. These manuscripts were rumored to have been preserved in the Great Library of Alexandria in Egypt, where early scholars and mapmakers would have had access to them. Despite a fire consuming most of the library’s scrolls and associated knowledge in the year 48 BC, Piri Reis specifically notes that parts of his map were derived from “maps drawn in the time of Alexander the Great," (350 BC). If this is true, then it hints at the possibility that not all of the pre-antiquity information held at Alexandria was destroyed in the devastating fire. It also implies that a previously unknown civilization was somehow able to obtain comprehensive knowledge of Earth’s southern geography.

Nazis? Not Sure.

While the debate rages on over whether or not ancient people once called Antarctica home, a similar argument has cropped up questioning the true extent of its modern day residents. According to historical record, “the secret land” of Antarctica continued to give up its mysteries throughout the 1800s as multiple public and private entities undertook expeditions with hopes of claiming territory. The 20th century saw deeper and further incursions toward the South Pole, with progress slowing dramatically in 1939 when World War II broke out. In the months leading up to declarations of war against Hitler, one unique German expedition has continued to resonate with rogue Antarctic researchers and provide fuel for speculation about the remains of a lost civilization on the continent.

The legends tying Antarctica to the Nazis are well traveled. These claims derive most of their inspiration from real events, as the Third Reich did launch an excursion to the southern continent in 1938 aboard The Schwabenland. While officially a mission to explore and exploit the area's resources, researchers suggest that some onboard held ulterior goals. Drawing on the Nazi penchant for esoteric knowledge and the occult, an alternative motivation is provided for their trip to the Antarctic. Members of the Nazi party were convinced that the German people were descendant of a distant, advanced race of humans, (known as the Aryans), who traced their roots back to the citizens of Atlantis. They created the Ancestral Heritage Research and Teaching Society, known as Ahnenerbe, to scour the world in search of support for their desired version of history. In their quest for Germanic links to Atlantis, theorists suggest that agents of the Ahnenerbe went to Antarctica to look for artifacts and other potential connections to the long-lost civilization.

After the Nazi convoy arrived on the eastern coast near Queen Maud Land, the crew began claiming territory for Germany while scouting for a suitable location to construct a whaling station. It was strategically important to extend their presence in the South Atlantic Ocean with the prospect of war on the horizon. During their reconnaissance flights over the mainland, German pilots documented startling snow-free oases complete with fresh-water lakes.

Assuming that there were pockets of satisfactory terrain peppering the continent, it’s reasonable to believe that the Nazis may have found a place to construct their Antarctic fortress.

Some curious pieces of evidence later surfaced that left the hatch open to the possibility of Nazis in Antarctica. Much stock is put in the official reports of wayward German submarines and their unaccounted for whereabouts at the end of the war. Two months after Germany’s surrender, a well documented series of incidents took place in a naval port in Argentina, not far from the northern reaches of Antarctica. Stoking theories that Hitler faked his death and escaped to a South Pole hideout were the factual accounts of U-boats U-530 and U-977. The German subs turned themselves in to the Allies well after the official ceasefire was signed. This led to speculation that U-530, the first of the two U-boats to appear, might have swiftly smuggled a living Hitler and Eva Braun, along with other high-ranking Nazi officers, out of Germany and deposited them safely in a hidden Antarctic base. When Nazi sub U-977 surfaced in the same location a month later, observers saw it as further confirmation of their theories. They estimated that enough time had elapsed to allow for the evasive underwater ships to scurry south from Germany and offload their “cargo” on the other side of the polar ice. Both U-boat captains denied any such plot upon interrogation by combined members of the U.S. and Royal Navies, but their refusals are hardly surprising and decidedly unreliable.

The circumstances surrounding the Navy’s 1946 Operation Highjump to Antarctica continue to raise questions about its true mission and motives. It’s admittedly strange that the Navy decided to send 4,700 sailors to the harsh conditions near the South Pole for training and exploration less than a year after the end to a long and brutal world war. Polar expedition historian Dian Belanger has written extensively on Highjump, and she agrees that, “it’s a little odd that they would have conjured up so many.” What could have been so important to the U.S. military for them to mobilize the largest naval entourage Antarctica has ever seen? The official reasons include conducting various cold weather exercises, performing tactical aerial surveys, and establishing a long-term outpost. All of these objectives could have been achieved with a considerably smaller force. Highjump’s goal of practicing maneuvers and operations in polar conditions could certainly have been undertaken much easier, cheaper and closer to home in the arctic north.

Alternative researchers believe a hidden Highjump mission also existed: to scout the continent for signs of a lingering Nazi presence. This theory makes sense. We know that Hitler’s army did visit the area just prior to the onset of the war. Beyond the official accounts, some claim that the German submarines discovered large, expansive caverns and adjoining temperate waterways beneath the glacial ice, making it an appealing spot for Nazi remnants to regroup if Hitler’s war campaign “went south.” Legends go on to tell how an epic battle eventually unfolded between the U.S. and Nazi forces on the Antarctic ice — and the Germans were able to resist the Navy's assault.

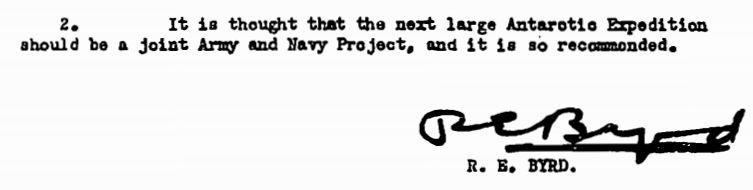

Despite historians downplaying the possibility that hidden bases or a concealed Nazi contingent was detected and engaged by Highjump, declassified documents reveal that a subsequent military campaign was being seriously considered. After the close of the operation, Admiral Byrd recommended that the next expedition, “should be a joint Army and Navy Project.” Why would the Navy request a return mission with additional military reinforcement if all that existed were penguins and icebergs?

But return they did in 1947 as part of Operation Windmill. Two icebreaker ships carried a flotilla of 500 men, including an elite Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) — a precursor to the modern Navy SEALS. One of the group’s primary functions throughout the second world war had been to, “destroy dangerous underwater obstructions.” Their unit was skilled at arranging and detonating submerged explosives on a large scale. These frogmen were also comfortable in high- stakes, unconventional situations and adept at operating in small, covert units to accomplish their top-secret missions.

If Operation Highjump was able to confirm the location of a last-stand Nazi stronghold through their extensive aerial photography and surveys of the Antarctic coastline, then Windmill’s aquatic bomb specialists would be an integral part of penetrating a subterranean entrance. Lending weight to this theory is the fact that the UDT exploded a 7,750 pound charge of underwater TNT off the Antarctic coast during the operation. If remnant Nazi forces were holed up in the southernmost latitudes, perhaps this highly-trained, exclusive unit was chosen by design to succeed where Highjump’s initial massive strike force failed.

Underground Nazis in the 1940s are as hard to confirm as a lost civilization 12,000 years ago. The evidence that exists is tenuous, sparse, and open to interpretation. This will likely remain the case as long as the countries involved in the signing of the Antarctic Treaty System stand guard with a steady perimeter presence. The arrangement guarantees that exploration is mainly reserved for authorized scientific study, ultimately preventing those with divergent agendas from having a seat at the table. Access to the continent isn’t exactly off-limits, but a guided expedition to the South Pole can cost over $50,000 for an individual — a prohibitive factor for most.

Perhaps the mysteries of Antarctica are meant to be concealed for reasons we don't understand. A member of the 1897 Belgian expedition best captured its enduring strangeness when he said: “The silence which broods at times over this unknown world is singularly impressive … this realm of eternal ice is so different from anything one has seen that it appears another world altogether.” Barring another one of Hapgood’s pole shifts, the truth about ‘the secret land’ will likely remain hidden forever under miles of stubborn glaciers and a tireless army of shifting pack ice.