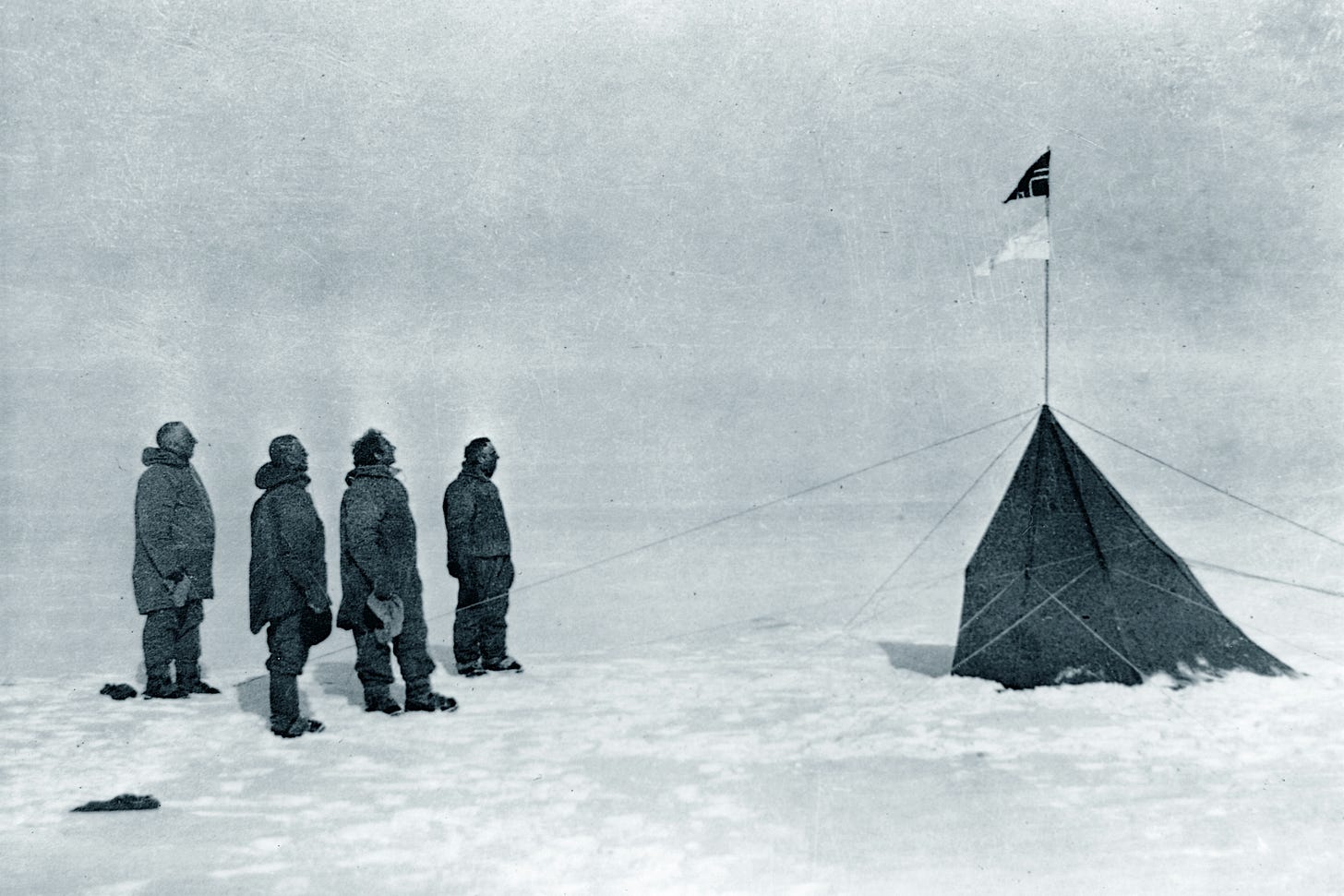

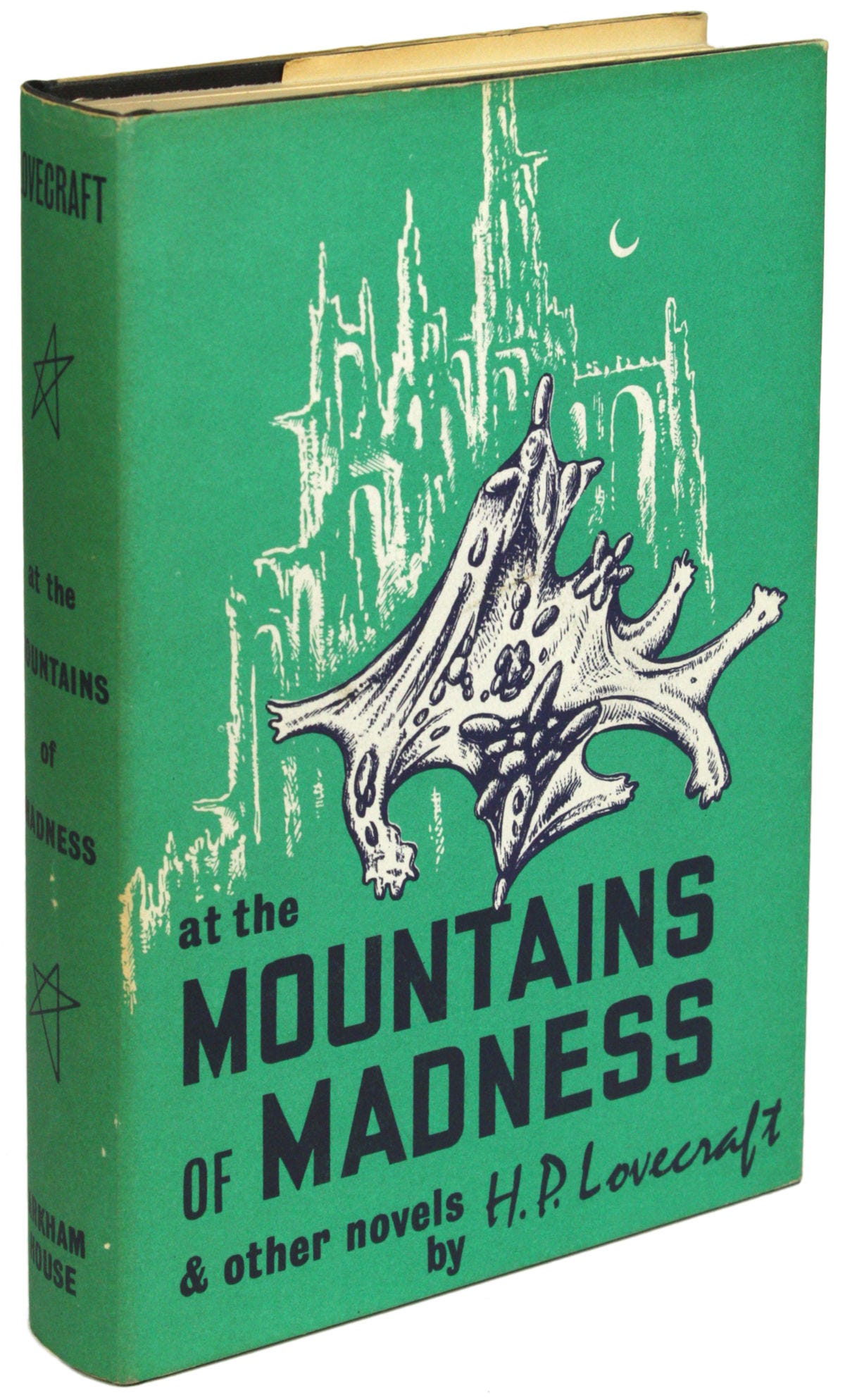

Science-fiction author H.P. Lovecraft had an obsession with the frozen landmass of Antarctica. He vigilantly followed the radio broadcasts of U.S. Navy Admiral Byrd’s excursion to the enigmatic continent while devouring the tales of grizzled South Pole expeditions from the likes of Amundsen and Scott. The unnatural and unexplored landscape was the perfect setting for his unique brand of cosmic-horror. In 1931, he wrote At the Mountains of Madness, a short story about a group of archaeologists exploring the remnants of an ancient extraterrestrial civilization discovered beneath the Antarctic ice. In Lovecraft’s tale, the subterranean city was home to our planet’s original inhabitants. His creatures had arrived in a time before the continents assumed their current positions.

Lovecraft was not alone in his preoccupation or his perception of the last uncharted continent in the world. An earlier story from author John Martin Leahy examined the fate of a trio of intrepid Antarctic adventurers as they documented the otherworldly horror encountered in an abandoned tent during their trek to the South Pole. Other fiction set in the craggy wasteland of Antarctica mimicked these themes — in the vast emptiness of such a dark, uninviting expanse, something ancient, supernatural and incomprehensible to human understanding awaited. Even after decades of occupation, the mysterious continent continues to hold the same allure.

Throughout recent memory, the white blanket draped over Antarctica has been seen as an attractive canvas on which to project fantastic theories and hard-to-prove assertions. According to dissonant ideologies, the frozen continent has witnessed everything from pole shifts and the ancestors of Atlantis, to Nazi bases and extraterrestrials. Like most studies that attempt to address topics of the unusual variety, the truth quickly becomes obscured behind a blizzard of unreliable data. Anchored within these turbulent legends are islands of fact that observers can use to chart their course through an uncertain sea.

We’re not in Pangea Anymore…

One of the foremost mysteries plaguing the land around the South Pole has to do with the timeline of its discovery and habitation by humans. It’s hard to imagine any group choosing to settle in the brutal arctic climate, yet ancient legends and maps tell of a body of land around the South Pole prior to the “official” date of human discovery. These artifacts seem to indicate that humans were aware of the continent's existence earlier than historians thought. Remarkably, some of these documents also show the continent free of snow and ice. Researchers from both ends of the spectrum agree that Antarctica wasn’t always covered in sheets of miles-thick glaciers, but they diverge on whether humans were ever around to witness it. Most earth scientists object to the timelines and explanations put forth by alternative investigators to explain how this could have occurred. When assessing the possibilities that antediluvian civilizations might have flourished on the piece of dirt known as Antarctica, it’s necessary to understand how Earth’s gigantic landmasses are thought to migrate across the planet.

Leading mainstream theories regarding plate tectonics describe how our continents are constantly in motion, albeit very slowly. Geologists widely believe that throughout our planet’s history, portions of our Earth’s outer crust have come together and and drifted apart multiple times, forming a plethora of fun-to-say supercontinents and superoceans (Gondwana, Rodinia, Thalassa Ocean).

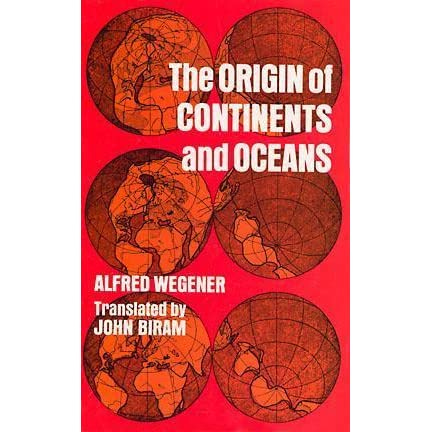

The idea took shape in 1912 with Alfred Wegener’s observations about the way coastlines of several continents seemed to “fit” together like puzzle pieces. He speculated that the outer layers of the crust were able to float around independently atop the lower layers, repositioning themselves in a process called continental drift.

Since his original “puzzle” thesis challenged accepted geologic models, Wegener was predictably dismissed by establishment scientists and saddled with the same moniker that fringe theories encounter today: pseudoscience. The Smithsonian describes a familiar behavior pattern, often displayed when conventional ideas become challenged: Wegener’s academic detractors, “joined ranks and tore holes in his theories, mocked his evidence and maligned his character.” Wegener was viewed as an uncredentialed interloper by “experts” in the field he was researching, and hypotheses involving his version of plate tectonics did not fully displace existing theories until the early 1970s (40 years after his death). So much for peer-review.

In the absence of a unified scientific answer, an alternate explanation for how our continents roamed about the Earth received wide circulation. Crustal Displacement Theory, refined by Charles Hapgood in his book Earth's Shifting Crust (1958), asserted that the planet’s landmasses were realigned through rapid movements of the entire outer crust, not individual plates. This resulted in dramatic, simultaneous relocations of the Earth’s continents.

Hapgood’s book laid out evidence suggesting the entire top layer of the Earth’s crust had shifted multiple times atop its viscous substratum. The exterior crust did not break apart or split into plates, instead it remained intact when it moved, retaining the relative spacing of the planet’s existing landmasses. This thrust the continents into new latitudes, bringing forth drastic changes in environment. The processes he describes would have also caused catastrophic climatic changes and pole shifts — a point that proponents of early Antarctic explorers cling to as a possible explanation for how the continent could have possessed a milder temperature more recently than scientists are willing to accept. If Antarctica had been located in a different spot on the planet prior to Hapgood’s proposed total crustal displacement 12,000 years ago, then theories involving ancient seafarers surveying the continent’s landscape would be within the realm of possibility.

Among other proof, Hapgood evidenced long core samples of soil brought back from Admiral Byrd’s excursions to Antarctica as proof that the land had recently been free from ice. Expert analysis determined that the samples of 10,000 year-old dirt found mostly fine-grained sediment present, “suggest[ing] an absence of ice from the area during that period.”

Scientists hate when the Earth moves quickly and most of them denounce ideas that include cataclysmic events playing a major role in forging our planet. Shunned by the mainstream, Hapgood and other catastrophists argued that our planet’s geologic history was characterized by periods of swift and violent upheavals — not by long, slow processes or gradual forces.

The skepticism surrounding Hapgood’s theory mirrored concerns raised earlier about Alfred Wegener’s proposed crustal movements, as neither could sufficiently identify a physical force strong enough to budge enormous portions of the Earth around the planet and into new climate zones. In Hapgood’s case, he initially blamed the congregation of ice around the poles for creating an unequal distribution of weight, thus inducing an eventual displacement. He later abandoned this hypothesis when it was soundly refuted, proving his ability to assimilate criticism and avoid dogmatic ways of thinking, unlike some “professional” scientists who reviewed his work. While few geologists argue against the theory that the continents have changed positions in the past, the mechanisms that could cause fast migrations over short durations of time have not been convincingly demonstrated.

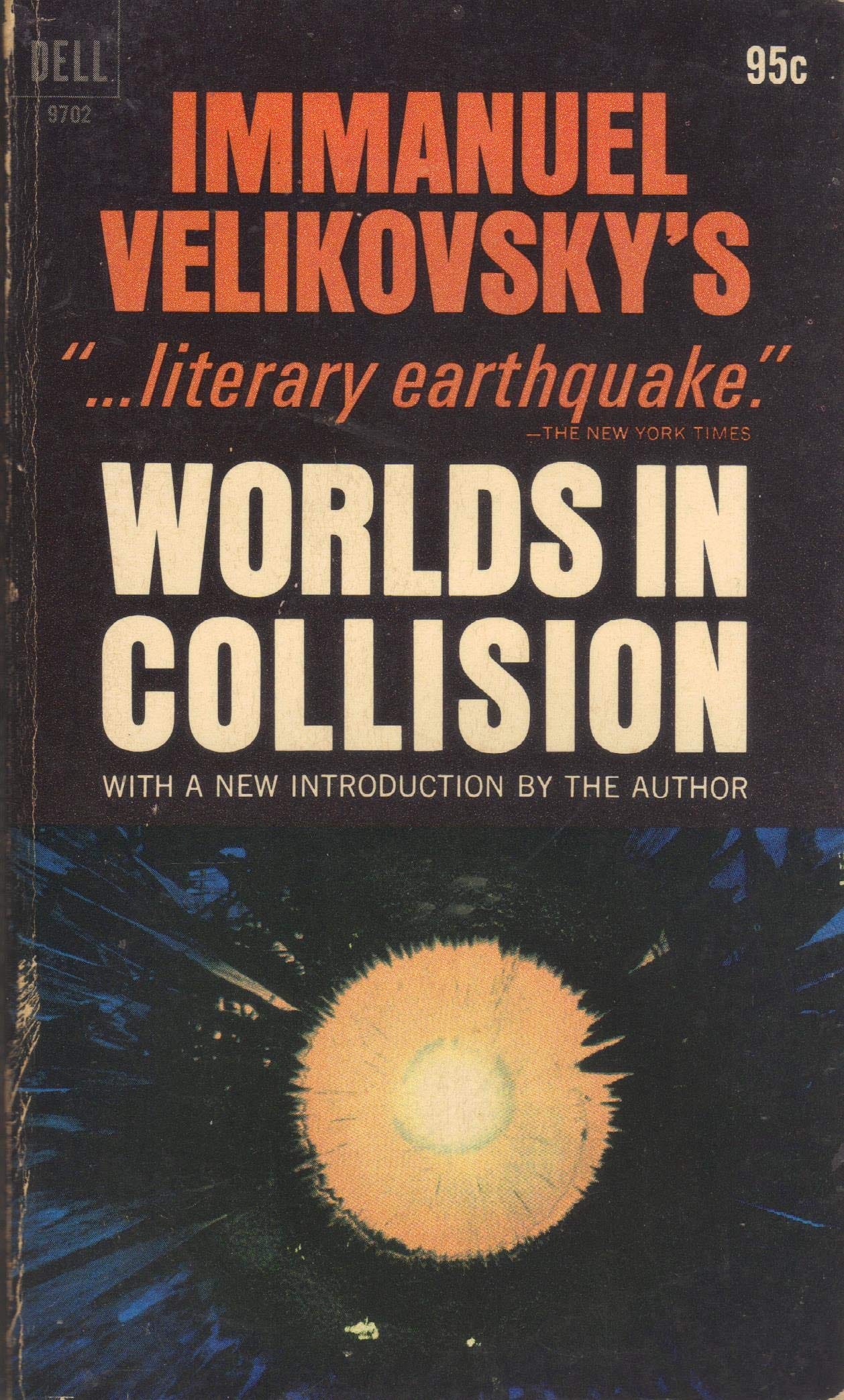

One possible catalyst for the energy required in Hapgood’s model lies in the controversial work of Immanuel Velikovsky. The Russian scholar published Worlds in Collision in 1950, putting forth his hypothesis that in the distant past, Venus had jettisoned from Jupiter as an immense comet in a hail of asteroids. Before settling into orbit around the Sun, this newly forming planet passed near enough to Earth, at times even colliding with our planet, to cause tremendous floods, earthquakes and pole shifts. Such an event could potentially account for the missing “force” mandatory for crustal displacement to occur.

Despite being rejected by most mainstream scientists, both Hapgood and Velikovsky did receive high praise from a very famous fan: Albert Einstein wrote forwards to books published by both researchers during their careers. Even with this lofty endorsement, their theories about catastrophic events and pole shifts causing dramatic and abrupt changes to the Earth’s continental layout were too contradictory to establishment modes of thinking, and have since been relegated to the intellectual borderlands.

Another point of view is championed by researcher and well-known author Graham Hancock in his seminal work, Fingerprints of the Gods (1995). He popularized a theory first advocated by close associates of Charles Hapgood, husband and wife team Rose and Rand Flem-Ath. They argued that Antarctica was swiftly relocated many degrees of latitude south at the end of the last Ice Age (ca. 12,000 years ago), taking with it the original citizens of the fabled lost-city of Atlantis. Weaving together many leading catastrophist notions with legends of Plato’s storied civilization, the Flem-Ath’s proposed that a massive crustal displacement took place and caused the land we know as Antarctica to shift underneath the ice already present around the southern pole. Hancock’s extrapolation of these theories was branded “pseudoarchaeology” by the academic fraternity at large, but their ridicule fell on deaf ears: Fingerprints has gone on to sell over five million copies.

The distinction between fast versus slow crustal advancement is important when considering the prospect of a long lost civilization inhabiting Antarctica. If portions of the planet’s surface did move as Hapgood and his adherents suggest, then rapidly shifting landmasses could conceivably slide into dramatically different global positions within a short period of time.

Despite a lack of physical evidence, believers hold out hope that signs of a pre-classical civilization in Antarctica, Atlantis or not, will be exposed by rising temperatures and other related Earth changes. Providing a potential blueprint for unearthing deeply buried evidence of early human habitation, archaeologists digging in frozen latitudes on the other end of the Earth have stumbled upon artifacts that only lately have become visible due to receding ice and snow. Some of their finds are over 10,000 years old, coinciding with the contemporary timeline that Hapgood and crew proposed for Antarctica’s temperate climate and potential discovery before it changed locations on the Earth. If pre-pole-shift peoples did exist on inland portions of the Antarctic landmass, it’s likely that any remnants will remain concealed for ages.

Or will they? Satellite imagery has captured some startling anomalies in the polar landscape that resemble man-made structures. The most eye-catching picture surfaced in 2017, showing an unnatural oval arrangement emerging from a snowy inland body of water. From the sky, the design resembles a fort or city wall, with perimeter dimensions estimated at 400 feet. This large formation is located in a formidable part of Antarctica, far from scientific settlements, making it hard for researchers to investigate from the ground. Commenting on the images, University College London archaeologist Mark Altaweel stated: “It’s the kind of thing that if you see it anywhere in the world, you immediately say ’that is definitely manmade’.”

A year earlier, images culled from Google Earth seemed to show a trio of four-sided, pyramid-shaped objects poking out of the bleak snow-scape. While most scientists concur that these formations can arise on their own in nature due to wind and erosion, their resemblance to the uniform shape and structure of the famous pyramids in Egypt is uncanny. These aren’t the first reports of strangely shaped formations on the continent. When the British Antarctic Expedition of 1910 explored the inland regions, they observed a different, “small but distinctive peak,” which they named ‘The Pyramid’ due to its appearance. Eric Rignot, a professor of Earth system science at the University of California, Irvine, soberly reminds observers not to make too much of the images, since, “many peaks partially look like pyramids.” However, he leaves room for interpretation by admitting that naturally formed instances, “only have one to two faces ... rarely four.” The ‘Pyramids in Antarctica’ were most likely formed from ordinary processes, but much like the other unorthodox features dotting the snowy landscape, more investigation is needed to know for sure.

Definitive? No. Conclusive? Far from it. But if these Antarctic discoveries prove to be the remains of an early culture, it’s possible that they were constructed at a time in history before the continent slid into Earth’s freezer box at the bottom of the planet.

Yet another theory that I find compelling is the Expanding Earth theory. As the name implies, the theory is that the earth was once much smaller, which is why the continents fit together pretty much perfectly, and that the earth itself expands over time, pushing the continents apart. I don't know what the engine for such changes would be but it might also create differences in gravity (and other factors) that might have influenced the growth of the dinosaurs and other enormous creatures that no longer exist - and probably couldn't under our present state of gravity. There are some videos on line that illustrate this theory.

It is really unfortunate that anyone who challenges, however mildly or logically, established scientific dogma, is usually ridiculed, attacked, censored, or even driven out of their field. I'm reminded of the very tragic case of Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis who first advocated the practice of hand washing in medicine - something so basic that we now take for granted, but he was destroyed by the "scientific" community for advocating this and died in an asylum, after much physical abuse. I don't think we've advanced much from that behavior. Here's his really sad story:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ignaz_Semmelweis