Killer Kodaks and Soul-Snatching Shutterbugs (Part 2 of 3)

Continuing our look at photo-phobia --- including historical and pop culture perspectives on cameras as soul-stealers.

Killer Kodaks and Soul-Snatching Shutterbugs, Part 2

Catch up on Part 1 here

“Dr. Baraduc thinks he has caught the human soul itself on his sensitive plates.”

Balzac’s conjectures about photographs stripping a person of physical layers of skin (see Part 1) may have been a source of inspiration for French researcher Dr. Hippolyte Baraduc (1850-1909), whose experiments suggested that cameras could capture a person’s “vital force” on film. His extensive collection featured photographs of white hazy blobs—the “vapour of life”—emanating from both living and deceased subjects.1 While his research had its fair share of detractors (one science magazine called his work “the borderland between science and quackery”2), Dr. Baraduc’s contributions illustrate how closely aligned photography was with concepts of life, death, and the unknown.

Predictably, critics disagree with the notion that an object’s aura is depleted whenever it’s mechanically reproduced. Mythographer (coolest title ever) Marian Warner argued that photographing something has the exact opposite effect—a picture “can preserve the vital energy of its long-vanished subjects.”3

Author Ian Knizek agreed, writing that there was “no very good reason why even reproductions cannot appropriate for themselves the features composing the work’s ‘authenticity’.”4

In an essay about the transferability of the human aura, Victoria Bigliardi proposed that “the aura does not disappear upon the loss of the original, but is reincarnated in the authentic reproduction.” In other words, a photograph can assume the original’s qualities and “becomes the very object to which it refers”—thus leaving the subject’s aura intact.5

No matter which camp is correct, both outcomes are equally worrisome.

If the photographic process doesn’t ensnare our spectral layers—if it simply peels them away—then each errant image contributes to the degradation of our bodily essence. If instead, photographs capture and retain the aura of the original subject, then a person with bad intentions might be able to exploit these totems at someone else’s expense.

It’s worth mentioning here that the pioneering photographers of the 19th century boasted above-average life-spans. In an era when most people failed to reach their sixtieth birthday, these camera jockeys regularly lived to be over ninety years old.6 Did early picture-takers discover a way to siphon the essence of life from their unwitting subjects?

Having established the persistence of photo-phobia across cultures and time, the question remains: where does this fear stem from?

Our uneasiness is partly a reflection of larger apprehensions about technology and its impact on traditional ways of life. Technological developments have a tendency to distance humans from nature and the natural world. Indeed, consider a common instruction given to anyone posing for a picture: “Smile for the camera!” This directive asks us to perform for the machine—not the person holding it or the people who might view it in the future.

Today’s experiences are increasingly moderated through electronic devices and mechanical equipment. Almost nothing is unfiltered by screen or image. This has a dehumanizing effect, and can distance us from the social and cultural interactions that have defined us for millennia.

In addition to technological insecurities, misgivings about photography exist because of its connection with death.

Pictures are memory portals—“transaction[s] that snatch instants away from time and imprison them in rectangles.”7 They evoke a sense of permanence, or lack thereof. Seeing photographs of our younger selves reminds us of our impending expiration date. Put concisely: “The photograph tells us we will die, one day we will no longer be here.”8 Pictures always reflect what was in relation to what is—which ultimately reminds us of what will be. The terror of nonexistence sparks a subtle aversion to still-images and the lifeless, “flat Death”9 they portray.

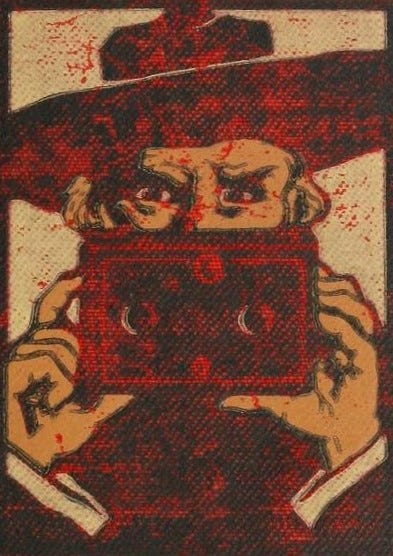

Fatal Framing in Popular Culture

In our age of science and innovation, you’d think that worries about photography’s sinister side would be obsolete. However, evidence from popular culture suggests otherwise. From comics to movies, there’s no shortage of stories featuring cursed cameras capable of inflicting harm. This recurring depiction speaks to society’s continued unease toward photo technology and all it represents.

Perhaps the most recognizable example of this motif (at least to a certain generation) is the wicked camera featured in R.L. Stine’s Goosebumps series. In its inaugural appearance in the book Say Cheese and Die!, a group of middle-schoolers stumble upon the eerie artifact in the basement of a dilapidated house. The device comes with a never-ending supply of film that takes pictures of events before they happen. Unfortunately, most of the predictive photos hint that something bad is about to go down—like car accidents, injuries, or an unexplained disappearance that coincidentally bears the hallmarks of a “Missing 411” case.

Eventually the kids catch up with the evil camera’s owner who admits that it “really does steal souls.”10 The original inventors of the cursed contraption were two PhD scientists—one of which was also a master of “dark arts.” When jealousy forces the duo to break up, a curse is placed on the camera for perpetuity. From that point forward, harm befalls anyone unlucky enough to get caught by its lethal lens.

The trope appeared decades earlier in the television series, The Twilight Zone. (In fact, the Rod Serling-penned, “A Most Unusual Camera,” was the inspiration for R.L. Stine’s Goosebumps rendition.) As the episode unfolds, we see two thieves fumbling with an unassuming old box camera acquired in their latest heist. They quickly discover that it produces photos revealing the future before it happens.

This revelation causes the group to voice concerns about the device that sound a lot like the ones expressed in the mid-19th century:

“This thing could come from witches or... sorcerers.”

“It could be loaded with black magic.”

“Where's the man with the horns who comes in with a bargain for the soul?”

Blinded by greed, the crooks use their newfound fortune to bet on ponies down at the track before eventually losing their lives to a series of events set in motion by the enchanted camera.

The 1990’s TV show Are You Afraid of the Dark also riffed on this narrative in “The Tale of the Curious Camera.” In the episode, a student (played by a young “Finch” from the American Pie movies) gets his hands on the aforementioned “curious” device. He quickly faces the same challenges as every other fictional character we’ve seen in this predicament. “Baby Finch” struggles to disarm the malicious machine before it produces more prophetic photos, and he soon discovers that the whole ordeal is the handiwork of a digital “gremlin” residing within the device.

What’s more, the creature has the power to project itself into other electronic devices—jumping into a video camcorder, a TV, and finally, a computer. This final scene does a wonderful job of depicting our primal fear about technology: no matter how quickly it evolves, negative side-effects will always keep pace.

A final example of the cursed camera formula in pop culture comes from a movie that exploits photography’s close association with death for a few cheap jump scares.

It’s been said that photographs “announce the death of the photographed;”11 and the barely watchable film Polaroid takes this axiom to heart. In the 2019 flick, a girl named Bird is given a camera that causes the death of anyone who poses for it. After her classmates’ bodies begin to pile up, Bird suspects that the device is bewitched by evil forces. We later learn that it’s saturated with the malevolent energy of a murderous high school teacher whose villainous spirit was transferred to the instrument after he was killed by police in the school’s darkroom.

In a twist that would make Balzac smile, every photograph taken by Polaroid’s cursed camera seemingly snatches the essence of its subject. When a picture is set on fire, those people get physically burned. When a photo gets crumpled, the subject is similarly disfigured in real life. This plot device is a nod to that age-old superstition that photographs can ensnare the “material residue of the person.”12 Indeed, if pieces of the soul can be retained on film, it might be the reason why the photos in Polaroid behaved like voodoo dolls.

The above examples of killer cameras and their fatal photographs reveal our ambivalent relationship with technology and the tension between humanity and the tools it creates. Chaotic narratives full of misfortune and negative outcomes (pun intended) are reflective of social anxieties about technology’s potential to disrupt cherished traditions and ways of life.

Part 3, Conclusion - Coming Soon!

“News and Notes.” The British Journal of Photography, November 19, 1897, p. 749.

The Electrical Age, vol. XIX, no. 3, Jan. 16, 1897, p. 45.

Warner, Marina. Phantasmagoria: Spirit Visions, Metaphors, and Media into the Twenty-First Century. Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 202.

Knizek, Ian. “Walter Benjamin and the Mechanical Reproducibility of Art Works Revisited.” The British Journal of Aesthetics, vol. 33, no. 4, Oct. 1, 1993, pp. 357–366.

Bigliardi, Victoria. “The Reincarnation of the Aura: Challenging Originality with Authenticity in Plaster Casts of Lost Sculptures.” IJSVR, vol.1, no.1, 2017, pp.72-80.

Walter Benjamin. “A Short History of Photography.” Screen, vol. 13, no. 1, Spring 1972, p. 17.

Morrow, Lance. “Imprisoning Time in a Rectangle.” Time, Oct. 25, 1989.

Cadava, Eduardo. Words of Light Theses on the Photography of History. Princeton University Press, 1997, p. 8.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections of Photography. Hill and Wang, 1981, p. 92.

Stine, R.L., Say Cheese and Die! Scholastic, 1992, p. 123.

Cadava, Eduardo. Words of Light. Princeton University Press, 1997, p. 8.

Warner, Phantasmagoria, 194.

A fine article!

However, let it be clear that the camera can catch the white translucent smoke of ghosts. It happens most often when the ghost has an unguarded group to draw from.

So, the question remains that if ghosts can be photograped, why not the vital aura?

The photo creates an independent image, a likeness and seals it in the moment. Is it truly using just chemicals and light, or it is capturing energy?

Any physical form is a manifestation of subtle force. We realize this upon perceiving death, that the subtle force has left, and the physical form will begin to decay quite quickly.

For indeed it then follows that the subtle force encompasses physical form and is its own sensory organ. Thus the image indeed steals life. The question is how severely.