Part 1, Part 3, Part 4

As is the case with most offbeat topics, reports regarding possible portal-places first passed through the pen of high strangeness aficionado, Charles Fort. In his book New Lands (1923), the father of Forteana wrote about “a triangular region in England” that endured oddities on a regular basis. Residents had to contend with seismic disturbances, exploding lights in the sky, and unexplained rocks falling from the air. Fort revealed that these things often happened simultaneously, with “shocks of this earth and phenomena in the sky at the same time.” He cleverly dubbed the area “the London Triangle,” providing a shape-inspired naming convention for another three-sided locale located in the Atlantic Ocean.

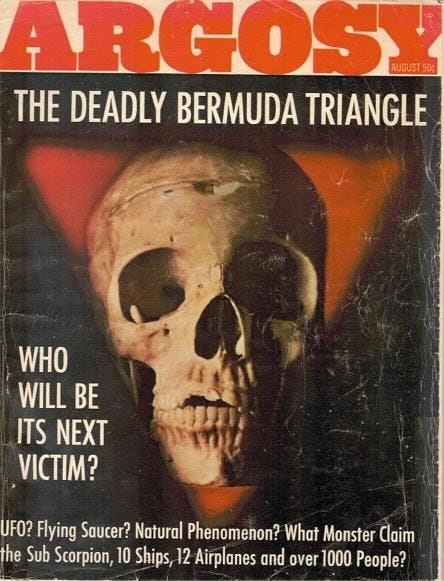

While Utah’s Skinwalker Ranch is arguably the current paranormal portal poster child, that honor was previously held by the Bermuda Triangle. In a 1964 article for the magazine Argosy, Vincent Gaddis introduced the masses to a peculiar patch of water off the coast of Florida that seemed to swallow ships, planes, and the occasional person. It established a lengthy legacy of weird goings-on in a “particular slice of the world” found between Florida, Puerto Rico, and Bermuda. His piece promoted the idea that certain regions on Earth were more vulnerable to strange phenomena than others, suggesting that the Triangle’s “hoodoo” might be the result of any number of vague and untestable hypotheses.

Wilbert Smith’s zones of reduced binding were floated as one option; as was the possibility of an “atmospheric aberration” creating “a hole in the sky.” The author sifted in ideas about gravitational and magnetic defects for good measure. The result is a laundry list of potential culprits culled from the borderlands of mainstream science.

Gaddis expanded his foggy notions about Earth’s mystery spots in Invisible Horizons (1965). He suggested strangeness at sea was due to “space-warps”—a phenomenon that could break down physical objects. Morris Jessup’s work was also mentioned, including theories about roving aerial hotspots with the power to dismantle planes.

Many researchers were beginning to suspect that portals could serve as gateways for things from another dimension. Gaddis wondered if places like the Bermuda Triangle boasted “an electromagnetic and/or gravitational vortex” that allowed otherworldly entities to enter our share of the spectrum.

He concluded that we live in an “apparently limitless universe” where “the unknown will ever ‘surround’ us,” and proposed that witnesses reporting ghostly ships or phantasmal planes might be seeing etheric manifestations crossing an “invisible horizon” from an unseen realm. These apparitions emerged from “a negative universe” that humans could only glimpse under the right circumstances.

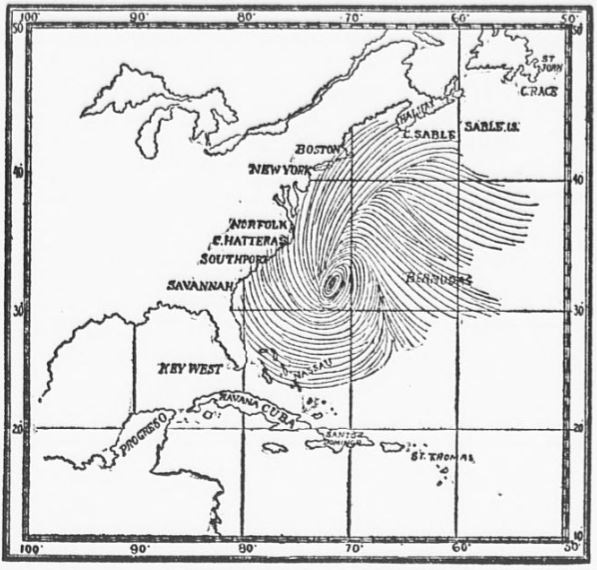

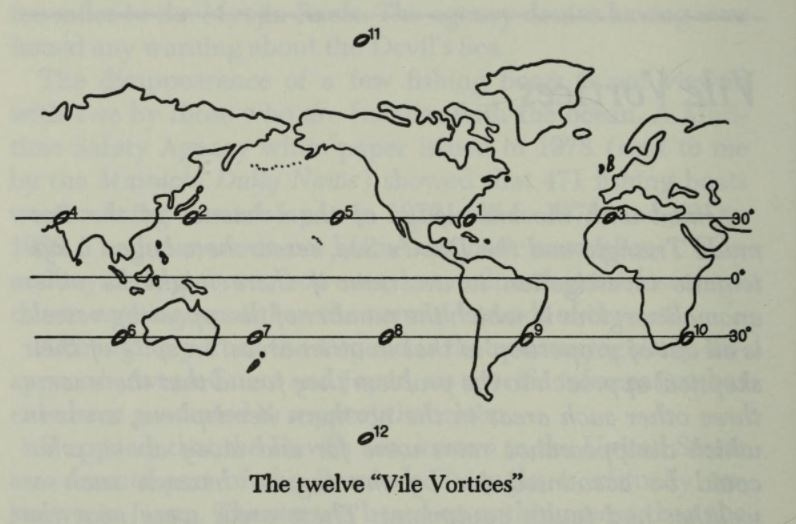

Not long after Gaddis’ article chummed the waters with weirdness, cryptozoologist Ivan Sanderson surfaced with speculation of his own. In his 1969 book, More Things, he took the idea of aqueous anomalous zones further by extrapolating them across the planet. He pinpointed 12 strange sites he dubbed “vile vortices”—aka “devil’s graveyards” evenly dispersed global “globs” that were inundated with “wild reports of poltergeist manifestations and an unusually high incidence of UFOs.”

In Invisible Residents (1970), Sanderson scoffed at “vociferous” ufologists that claimed vortices like the Bermuda Triangle were a “collecting ground” for ET craft. He didn’t buy that they were breaches where alien interlopers would “descend upon us to collect specimens of us and our machines.”

He favored the idea that these locations were cursed with a confluence of terrestrial processes: “The oddities, enigmas, and horrors allegedly noted in the vortices may be entirely natural and indigenous to certain areas of our Earth’s surface.” A majority of the regions featured swirling ocean currents and gravitational distortions, leading him to wonder what might occur if these forces were ever combined with an electromagnetic trigger event. Perhaps an interdimensional portal?

Not everyone was convinced about the reality of Sanderson’s ‘dirty dozen.’ In The Bermuda Triangle Mystery Solved (1986), skeptic Larry Kusche accused him of manufacturing the vile vortices by concentrating his search for unexplained phenomena in predetermined areas that fit his expected model. This form of confirmation bias is a trap that ensnares many researchers who set out to discover a pattern of strange events in a specific city or state. When people start to believe that weird things are happening in a specific area, they’re more apt to look for (and find) evidence supporting their contention.

While Ivan Sanderson provided a planetary pattern for the placement of portals, other investigative authors found evidence that these anomalous zones were far more widespread and haphazard than the ‘vile vortices’ would have us believe.

Part 3 Coming Soon!