“The surface of the Earth consists of land, water, air, light, life, and mind.”

-Sir Halford Mackinder

There’s a scene in the first episode of the TV show True Detective that finds Matthew McConaughey’s character describing the psychic atmosphere present in an area where brutal, occult-tinged murders have taken place: “I get a bad taste in my mouth out here. Aluminum. Ash. Like you can smell the psychosphere.” The investigation ultimately leads to a group of elite occultists whose abhorrent ritualistic behavior seems to have generated a palpable dark energy in the region. The show insinuates that their actions and emotions directly feed into this invisible “psychosphere,” which is subconsciously perceived by the area’s inhabitants.

Theories about the psychosphere are akin to Jungian notions of a collective unconscious—an invisible realm said to hover on the edges of our five senses. Psychoanalyst Wilfred R. Bion called it the domain of “thoughts without a thinker.” Advocates argue that we share this psychic energy field with everyone on the planet, creating a framework that connects our individual thoughts and deeds to part of a larger whole. Our emotional and mental states both dictate, and are shaped by, the psychosphere—we get out what we put in, and vice versa. The idea that this repository for human cognition is pliable and open for influence has also led to speculation that it’s possible to manipulate the psychosphere toward a desired outcome.

Early concepts about the existence of a psychosphere were developed by mainstream scientists. Oceanographer John Murray acknowledged the psychosphere in 1913, writing that it was a terrestrial construct—“a sphere of reason and intelligence.”

This same understanding was advanced by the Vice President of the National Geographic Society, W.J. McGee, who elaborated in an 1898 speech that the psychosphere amounted to the “social fabric, the expression of thought and purpose … the scanty but potent and ever-growing mantle of thought which today envelops the world.”

Pioneering British geographer, Sir Halford Mackinder (1861-1947), defined the psychosphere as a distinct region of the planet, just like the Earth’s hydrosphere and atmosphere. He also recognized the impressionable nature of this invisible psychic arena, noting its responsiveness to human thought: “Ideas constitute an independent force which grows in strength with improved technical knowledge and social organization.” These ideas form a tangible region, intertwined and influenced by the variables it absorbs: “The interplay of the forces of the psychosphere has become a closed system; their action in any part of the world is felt throughout the whole.”

Mackinder was also prescient when discussing the potential impact of passing information via “electro-magnetic waves” (radio and television). These emerging technologies held the potential to deliver “stimuli to imagination and mandates to action” on a large scale and in a coordinated fashion.

While psychologists and geographers sought to define the human mental-field from a scientific point of view, others approached it from a metaphysical perspective.

Early modernist writer Olive Moore (1904-ca. 1970) explored the concept on a galactic scale in her collection of essays, The Apple is Bit Again (1934). She described the psychosphere as a “layer rich in soul element” that occupied an area just above the stratosphere. She speculated that it might even go so far as to “intersect” with other psychospheres in outer space and establish “inter-planetary contact”—a cosmic collective unconscious.

Likewise, philosopher Oliver Reiser (1896-1974) proposed a far-out mechanism for connecting humanity to a larger whole. He refined the theory of “cosmic humanism,” which emphasizes the connection between man and the infinite universe. He posited that Earth’s communal psychosphere existed within a circumglobal layer of supercooled helium far above the planet. This “psi-field” acts as a conductor and repository for information (a home for the “Cosmic Mind”), and is accessible to guide our species’ cognitive and spiritual development.

In Messages to and from the Universe (1985), Reiser rejected what he called the “under the hat theory of consciousness,” and argued that it wasn’t merely derived from the mind of the observer. The psychosphere existed as an etheric “memory-field” that everyone could tap into, while simultaneously being tapped.

Reiser’s musings were bolstered by the experimental results of quantum researcher Andrew Cochran. He discovered that certain elements of matter displayed “life and mind properties” and went on to suggest that “living organisms are a direct result” of these “conscious properties of matter.” His work was used to show how quantum mechanics and subatomic entanglement might explain some of the unified behaviors exhibited by the psychosphere.

“An individual is not distinct from his place. He is his place.” -Gabriel Marcel

Historical depictions of the psychosphere describe its global (sometimes cosmic) scale—but can it also express itself locally? Do particular areas provide ingredients for a pronounced regional flavor? Indeed, there are places we visit that seem to rejuvenate our soul, and others that give us the creeps. The mountains can feel awe inspiring, while a dense forest might seem ominous or foreboding. Geography and the physical landscape subconsciously impact the emotional climate of the people living there—which contributes to the creation of a ‘localized’ psychosphere.

Mackinder discussed his philosophy on how humans interact with, and are shaped by, their physical environment: “Natural regions influence the development of communities inhabiting them.” He goes on to explain how these societies modify their surroundings, and “these regions, so modified, influence the communities differently than before.” He wasn’t only referring to the type of homes they built or how they arranged their villages—he understood that the psychological state of an area’s residents was partly an expression of their physical setting.

This relationship between humans and the places they dwell informs the art of feng-shui.

According to sacred site researcher Martin Gray’s definition, feng-shui is “the practice of harmonizing the chi of the land with the chi of human beings for the benefit of both. Temples, monasteries, dwellings, tombs and seats of government were established at places with an abundance of good chi... These naturally occurring power places that were structurally altered by humans became some of the primary sacred sites of China.”

Architects of the 19th and 20th century took these same principles to heart when situating mental- health facilities on acres full of nature’s beauty. This therapeutic approach hinged on the notion that the landscape would aid in the process of psychological healing.

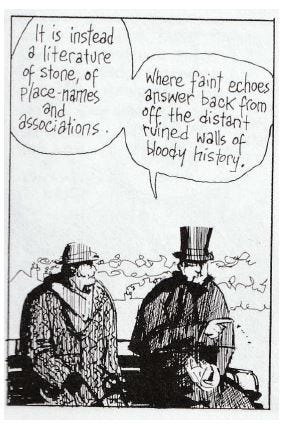

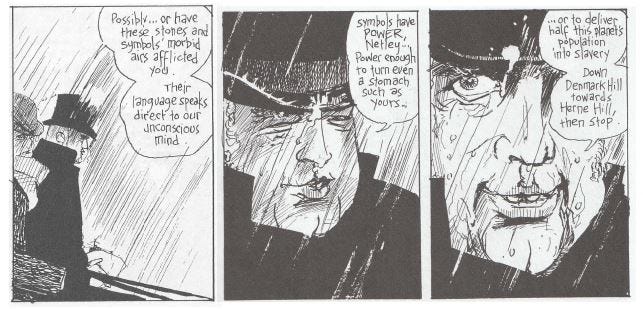

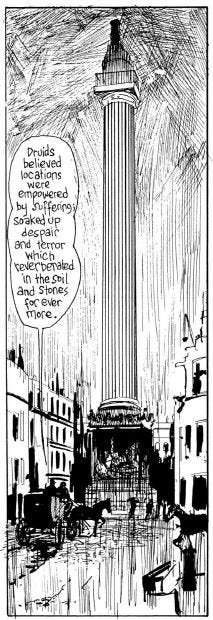

Writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell explore the darker side of this concept in From Hell (1999), their graphic retelling of the Jack the Ripper murders. In their book, the creators explore the impact that both natural and artificial surroundings have on the development of the citizens of London. Before carrying out his murders, the alleged Ripper takes a carriage ride around the city, pointing out the ancient druidic monuments and landmarks consecrated to prehistoric religions. He paints London as the result of centuries of spilled blood and ritualistic sun-worship—a heritage immortalized in the city’s layout and architecture. These images subliminally impress themselves on the local population, who project their resulting emotions into the psychosphere.

From Hell points out how the populace is surrounded by hidden reminders of these ancient rites, and blames the combination of man-made altars and residual psychic energy for infusing the immediate area with a malevolent aura.

The idea that an area of land can retain an emotional imprint and contribute to the quality of the psychosphere is considered by author Peter Levenda in his book Sinister Forces (2005). He posits that certain sites “are invested with super-natural power,” and illustrates this concept by visiting Charles Manson’s hometown of Ashland, Kentucky. After getting an uneasy feeling during a tour of the town, the author notes how “odd bits and pieces of Ashland’s history and geography seemed to swirl around a darker, more sinister core.” The infamous serial killer grew up among the ancient graves and cemetery mounds left by an enigmatic Native American culture that thrived along the Mississippi River valley. Features of the local landscape are a constant specter of death, both visually and subliminally, and Levenda believes the sacred hills are imbued with an energy that fuels the local psychosphere.

“Americans seem to be unconsciously aware that the mounds are repositories for something more than piles of crumbling bones.” Was their disturbance to blame for generating “sinister forces” that haunt the landscape? Perhaps there is truth in stories like The Shining and Poltergeist, where negative energies linger in the buildings constructed over Native American burial grounds.

“And by the psychosphere is meant the space of interaction among psychic systems such as languages, symbols, artifacts...” -Dr. Tetsunori Koizumi

That an image or symbol can evoke a response in the subconscious mind is a fundamental tenet of Jungian psychology. It suggests that the collective nature of the shared unconscious—the psychosphere—can cause people to respond in predictable ways to certain motifs and archetypes. If true, might someone with knowledge of this arcane lexicon be able to manipulate people toward a desired outcome?

A contingent of conspiracy researchers say yes. Controversial author Michael A. Hoffman II believes an occult-elite has mastered the ability to tamper with the psychic-ambiance of a population. In a series of books, he documents the rhetoric of the subconscious—what he calls “twilight language”—that is used to implant messages into the psychosphere. Through the covert use of symbols, ritual, and propaganda, Hoffman alleges that hidden groups seek to debase the state of humanity. Mass media acts as a Trojan horse for the campaign, using “seemingly run-of-the-mill news conferences, book illustrations, audio recordings and films to send coded messages.” These broadcasts saturate the airwaves and minds of viewers with carefully-chosen stimuli, who in turn deliver the anticipated reaction back into the psychosphere.

Japanese tea-drinking ceremonies exemplify the notion that explicit customs and context can activate a specific response—its routine consists of carefully selected elements, arranged to elicit a reaction. Daisetz Suzuki, author of Zen and Japanese Culture (1970), described how the purposeful movements and hand-picked paraphernalia that adorn tea- drinking ceremonies create the intended frame of mind for the participants: The event is “not just drinking tea, but involves all the activities leading to it, all the utensils used in it, the entire atmosphere surrounding the procedure, and last of all, what is really the most important phase, the frame of mind or spirit which mysteriously grows out of a combination of all these factors.” An individual’s ability to influence the psychic- environment—what Suzuki refers to as “the art of cultivating what might be called the psychosphere”—is possible through the deployment of ritual and symbolism directed at the participant’s subconscious.

A more gruesome example of this effect can be seen beneath the surface of the symbolically-charged Jack the Ripper slayings depicted in From Hell. These actions affected the psychosphere so severely that they prompted a synchronized reaction in the broader population. The killings were meant as a grand ritual to bring about a change in society—and their shocking brutality and blatant disregard for life acted like a blunt instrument plunged into the heart of the psychosphere.

Hoffman believes “mega-rituals” such as these are intentionally designed to reverberate across the collective psyche. Pumping this negative feedback into the closed-system results in a “psychic pressure cooker” that the practitioners believe will facilitate “the transformation of human beings.”

Charles Manson, Jack the Ripper, the 9/11 attacks—these traumatic events massively disturbed the psychosphere and left a scar on the global consciousness. When doused in a heavy coat of symbolism, the message is picked up and amplified by our subconscious mind, sending ripples throughout the psychic field. Peter Levenda observed this theme in the assassination of president JFK—a public mega-ritual that altered the social psyche of a nation—identifying the incident as “a bloody sacrifice replete with iconic resonance.”

Not everyone accepts the premise that subliminal messages can be deliberately deployed. One of Carl Jung’s protégés, psychologist M.L. von Franz, didn’t think it was possible to hijack archetypal imagery or symbols to invoke a premeditated response: “No deliberate attempts to influence the unconscious have yet produced any significant results.” While her point about the unreliable nature of the human psyche is well taken, evidence shows that tweaking certain elements of the psychosphere can have a demonstrable impact on its audience.

More than simply a new-age or psychological construct, the psychosphere is recognized as an extension of human consciousness—of collective thoughts, ideas, and emotions. Created through a witches-brew of internal and external influences, it binds everything it interacts with into a unified whole, responsive to the input of its constituents. As the world becomes more proficient in the language of subconscious, psychic exploitation of this global extra-sensory field remains a very real possibility.

Reminds me of egregore and Lucifer and psychic vampires.

An egregore (pronounced egg’ gree gore) is a group thought-form. It can be created either intentionally or unintentionally, and becomes an autonomous entity with the power to influence. A group with a common purpose like a family, a club, a political party, a church, or a country can create an egregore, for better or worse depending upon the type of thought that created it.

A fascinating collection of musings about consciousness, including the extent to which sinister activity can affect a landscape for many centuries thereafter. Excellent post, whose references I will follow up! Keep up the good work.