“God cannot alter the past, though historians can.” -Samuel Butler

Anatoly Fomenko is a slim individual with a perpetually disheveled, academic appearance. His speech betrays a slight lisp that manifests itself often when pronouncing words in his native Russian. He doesn’t have the presence or demeanor one would expect from a man seeking to shred every long-held doctrine of conventional history, but if his theories about “phantom” or nonexistent periods of time in our past are true, there won’t be a timeline left intact.

Like many revisionist theories of the fringe variety, Phantom Time Theory gained popularity due to the work of an Eastern European scholar. Born in Ukraine and educated in Russia, Dr. Fomenko is an accomplished mathematician and tenured professor at Moscow State University. In a rare move for a PhD in mathematics, he’s spent much of his career introducing concepts that shake the framework of history. His foray into upending the accepted narrative began in 1973 after he discovered that “the consensual versions of chronology, as well as those of ancient and mediaeval history … appear to contain major flaws.”

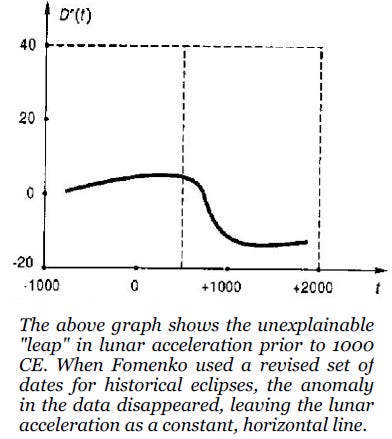

Fomenko’s first clue about a potentially fabricated past and dubious computations of time came from “a strange contradiction” plaguing scientists attempting to calculate ancient lunar movements. Prior researchers were using widely- accepted dates established by historians to chart the rhythm of eclipses and other astronomical events through the ages. This adherence to the mainstream historical timeline led to an unexplainable deviation in lunar acceleration, appearing most dramatically around the year 1000 CE. Fomenko believed that this irregularity “[could not] be explained by conventional gravitational theory.”

Mainstream astronomers couldn't account for the data oddity either, so they came up with an unconventional explanation. Refusing to abandon traditional chronology's dating of eclipses, they invented a one-of-a-kind gravity event to explain the inconsistencies in past lunar data. Unsatisfied with this flimsy interpretation, Fomenko began re-plotting the Moon’s historical acceleration using a computer-assisted recalculation of dates for past eclipses. He obtained these updated astronomical tables from another notable Russian revisionist and chronology skeptic, N.A. Morozov. This new approach ironed-out the anomaly that was haunting astronomer’s previous models while eliminating the need to invent an inexplicable act of gravity.

Encouraged by his results, Fomenko used the revised dates to examine the historical record for astronomical synchronisms (similar celestial events recorded across different historical accounts). These synchros indicated a possible overlap (or duplication) of the same narrative. After identifying numerous examples of ancient and medieval chronicles that appeared out of place based on poorly dated astronomical events, Dr. Fomenko and associates came to the conclusion that our current understanding of ancient history was wrong — a “fairy-tale phantom-mirage, created by the historians.”

To illustrate his point about incorrectly dated astronomical events and their influence on the accepted version of chronology, Fomenko cites a trio of eclipses supposedly recorded in the 5th century BC by the respected historian, Thucydides. According to our current understanding of ancient celestial movements, this type of lunar three-peat only appeared in the sky in the years between 1000 - 1200 CE. Fomenko and associates conclude that Thucydides was likely describing real eclipses in his chronicle, which meant he must have been alive and writing in the 11th-12th centuries. Any historical accounts placing him and the events he describes in 400 BCE were inaccurate by a measure of thousands of years.

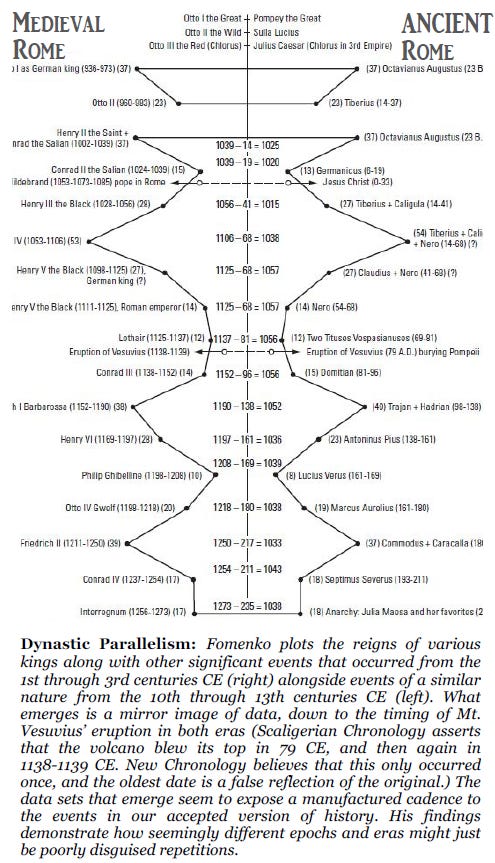

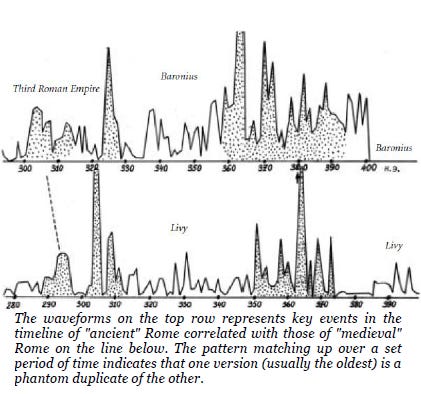

Realizing the implication of his discoveries, but needing additional objective proof, Fomenko turned to his strength in statistical analysis. His team designed an approach to locate meaningful parallels between different cultural narratives and ancient texts. Ruling dynasties, the lengths of reigns, wars, noteworthy individuals, and other important events from all historical ages were quantified and mapped visually. Using these variables, Fomenko searched algorithmically for “hits” — blocks of time that appeared to match-up in statistically significant ways with one another. If enough data points/correlated events from Period A correspond with those in Period B, it increases the likelihood that one of them is a period of phantom time.

Some of the best evidence for this type of historical tampering comes from examples of dynastic parallelism. Dynastic parallelism consists of strongly correlated series of successive ruling dynasties occurring over similar time spans, but across “different” cultures or eras. Imagine a king ruled for 20 years, followed by his son for 10 years, only to be usurped by a new dynasty for the next 50 years. Fomenko’s approach takes this string of events and searches for analogous instances of the succession pattern across different regions and epochs to determine if one is potentially a falsely planted carbon copy brought backwards in time.

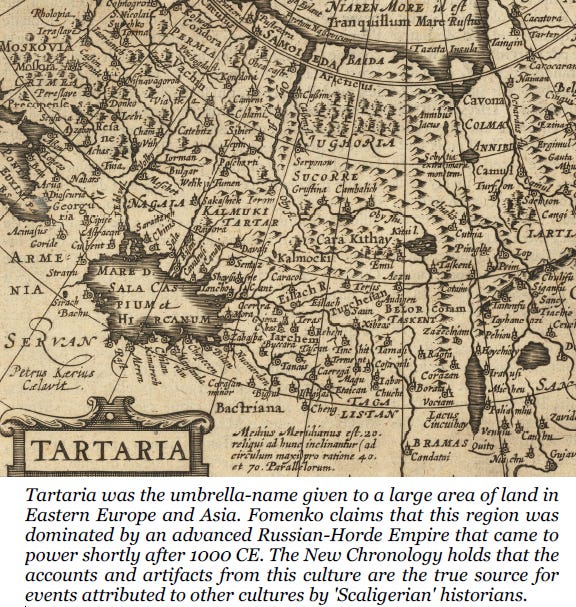

Armed with this information, Fomenko set out to reconstruct a revised chronology of human history — one that was dramatically shorter and less ancient than historians originally created. His research revealed that major portions of today's accepted timeline were deliberately forged in the 16th - 17th centuries by “aristocracy, clergy, and humanists” — conspirators aligned with the political elements of Western European Christianity and the Roman Catholic Church. These chronologists were tasked with creating a fictitious version of antiquity that served a decidedly Western European/Catholic agenda. According to Fomenko, this also meant completely erasing the grand history of a globe-spanning, pre-16th century Russian civilization.

Dr. Fomenko goes on to explain how “most events of “Ancient” History took place from the 11th to the 16th century, were replicated on paper in 1400-1600 AD, and positioned under different labels in an imaginary past.” The devious editors of antiquity concertedly rewrote the ancient texts, inserting dates and events to make them appear far older than they were. In order to construct a timeline that fit their needs, these early chronologers started with contemporary people and occurrences as inspiration before systematically echoing different versions of them backwards in time. Any records, artifacts or documents that couldn’t be altered were destroyed in an attempt to control the narrative of the past while reconstructing a misleading version of history to leverage in the future. This fake heritage provided emerging Western European nations and religious denominations with a manufactured legacy upon which they could build as their power and influence solidified in the 17th century. This nefarious plot was surprisingly easy to pull-off since there were only a handful of ancient narratives that historians relied upon when creating the world’s traditional chronology.

“New Chronologers” take special issue with the timeline assembled by Joseph Scaliger in the 1580s. Scaliger attempted to assimilate the chronologies of Middle Eastern cultures like the Babylonians, Persians and Egyptians with those of the classical Greek and Roman accounts. He scrutinized various ancient calendars and methods of timekeeping to construct a comprehensive and linear version of human history. Despite legitimate criticisms about his lack of knowledge in the areas upon which he relied to create it, Scaliger published his version of a cohesive world chronology in a 1583 book, Opus de emendatione tempore (Study on the Improvement of Time). His work went on to survive for centuries with little refinement, standing as the principal interpretation of the human cultural timeline despite its inaccuracies and falsehoods.

Fomenko’s theories and techniques can be hard to keep organized, but his overarching argument is that more than 1,000 years of collective human history never happened. Sources pretending to recount events from years prior to 1000 CE are deliberate counterfeits of real occurrences that actually took place during 1000-1500 CE. He rejects the idea of the so-called “Dark Ages” in European history (where few historical records survive to elaborate on the time period), claiming that any “dark” age is evidence of purposeful suppression. For religious and political reasons, the 17th century ruling elite commenced a global effort to alter or destroy the true version of history prior to 1600 CE and supplant it with a false one. This enormous undertaking was perpetrated by Western European elements in order to contrive a glorious history for themselves while simultaneously eradicating all traces of an advanced Eastern European/Eurasian Empire that had flourished during the preceding epochs (referred to as Tartaria on early maps).

Confused yet? So were we — but the methodologies behind the New Chronology become more tangible when they’re brought down to just one of the multiple “time-shift” models put forth by Fomenko.

He found that a lot of historical manipulation held consistent over a set measurement of time. For example, “Ancient Rome” (750-236 BCE) and “Medieval Rome” (300-816 CE) are approximately 1,050 years apart on the traditional timeline. His statistical analysis of these two eras found that series of seemingly “different” historical events appear to share a common pattern. This is a signal that the “Medieval” Roman narrative was possibly duplicated and shifted backwards in time by 1,050 years to create a false history for an “Ancient” Rome.

While Scaligerian Chronology tells us that there were different and distinct eras of Roman history, Fomenko believes that this empire existed only once. He arrived at this conclusion by graphing the two time periods using a statistical approach. Significant events in either era are represented as peaks and valleys based on their duration. When enough of these formations sync up, the potential is high that one series is a historical rip-off of the other.

His analysis revealed a large correlation between multiple variables in both eras — indicating that “ancient Rome and mediaeval Rome are probably the same thing.” (Fomenko also believed that BOTH Roman retellings were actually describing the Russian/Eruasian Empire, which historians later obscured from history by deleting them from source documents.) Fomenko and team don’t think these similarities can be explained as coincidence. Instead, historical stories and characters were simply distorted reflections of real events that had taken place more recently.

To correct this historical injustice, Fomenko compiled a different interpretation of the past, calling his timeline the New Chronology. He lays out his reasoning in a number of lengthy books — the magnum opus being a series titled History: Fiction or Science? Here he applies his statistical methodology to demonstrate the unreliability of, “the entirety of historical records.” The New Chronology doesn’t deny that many of these events happened at some point in the past, but Fomenko’s reconstructed timeline places them in “their more probable positions on the time axis.”

Today's New Chronologers are not alone in their suspicions about a fabricated historical record. Scientific stalwarts like Isaac Newton also gave the side-eye to chronologies produced in his day, prompting him to author a manuscript rectifying these prevailing historical inconsistencies. In The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (1758), published after his death, Newton took aim at contemporary chronologers responsible for constructing a misleading account of history. For example, when the numbers didn’t add up for historians trying to prove the longevity of ancient Greece, they “sometimes doubled the persons of men;” outright inventing kings and periods of reign to account for the additional centuries woven into the fabric of accepted history. These “repugnancies,” as Newton called them, resulted in severely misdating “the Antiquities of Greece three or four hundred years older than the truth.” His frustration with these historical fabrications is palpable: “By such corruptions they have exceedingly perplexed Ancient History.”

Similarly, the Egyptian priests sought to inflate their lineage and antiquity by creating entire centuries of counterfeit pharaohs. Newton claimed that they “very much increased the number of their Kings,” out of “vanity.” Proving the amount of damage one could do with a pen, Newton erases 11,000 years of Egyptian royalty with a couple of sentences: “but the Egyptians, for making their Gods and Kingdom look ancient, have inserted ... three hundred and thirty Kings of Thebes, and supposed that these Kings Reigned eleven thousand years; This being a manifest fiction, we have corrected it, by omitting those interposed Kings.”

Newton relied on his advanced astronomical observations and subsequent calculations to determine the points in time of notable equinoxes, solstices, and other heavenly happenings more accurately than his predecessors. With the aid of disparate historical accounts, he was able to “date” the events unfolding on Earth in relation to these celestial occurrences.

As one Princeton critic opined about Isaac Newton’s version of chronology: “...extremely dull and inhuman; people live and die, cities are founded and are destroyed, kingdoms rise and fall with no trace of individuality or character, only intricate argumentation about dates.”

That was precisely his point — as an empirical scientist, Newton’s goal was to construct a logical and finite account of history.

Jean Hardouin was another early “historical skeptic” whose work in the late 1600s set the stage for many of the researchers who would later build on his assertions. He wrote his treatises through an unapologetically Jesuit filter, and as such he was more or less ideologically opposed to a separate branch of Catholicism promoted by Benedictine monks. In the era before printing presses, the followers of St. Benedict were famous for ravenously devouring ancient texts in order to individually transcribe additional copies by hand. With a corner on the early reproduction market, the Benedictine’s who duplicated manuscripts had a fair amount of leeway to alter the details of these works and distribute their modified versions to the rest of Europe. Hardouin and the Jesuits were relatively new on the Catholic scene during the time he was writing (the order was founded in 1534 CE). The Benedictines had a significant head-start, forming their monasteries in the 500’s CE. This allowed the group ample time to spread their writing and influence, often bringing them into conflict with the later teachings of the Jesuits.

In the introduction to his book, The Prolegomena (The Prologue to the Censure of Old Writers), Hardouin contends that our warped understanding of history was the result of an intentional ruse hatched by “a certain band of fellows ... who had undertaken the task of concocting ancient history.” These spurious authors “joined forces in the writing of History,” by furiously copying one another’s edited manuscripts to perpetuate their version of events. These documents were then slowly leaked into the libraries and minds of the rest of the world. Since most of the books in circulation were churned out of Benedictine monasteries, Hardouin insists that the monks used this bottleneck to their advantage and only produced versions of historical narratives that fit with their agenda.

When he isn’t solving esoteric mathematical riddles or reconstructing the timeline of human history, Anatoly Fomenko finds time to be an artist. His artwork is dominated by surreal scenes and often overtly apocalyptic imagery. Nods to geometric principles embracing logic and order are inherent in the rigidness of his black and white compositions. Comparisons are usually made to the patterned artwork of MC Escher, but unlike the overly repetitive arrangements that Escher composes, Fomenko’s warped and melting figures invoke the surrealist paintings of Boesch or Dali.

Anatoly the artist receives inspiration from a field of mathematics known as topology. Topology is concerned with the properties of shapes that are preserved after being subject to continuous deformation. “The motivating insight behind topology is that some geometric problems depend not on the exact shape of the objects involved, but rather on the way they are put together.” This perfectly describes Anatoly Fomenko’s relentless pursuit of an accurate and orderly chronology — the pieces of the past are there, but they've been assembled incorrectly. Time will tell if his version shifts history in the right direction.