Warning! If you have not seen the movie, and intend on doing so, then don’t read any further. Beware! Plot spoilers ahead!

NOPE—the new “flying saucer” movie from director Jordan Peele—has generated a lot of hype since its release. Does it deliver? The Observer’s media correspondent trekked to the theater on opening weekend to analyze the film from a UFO buff’s perspective.

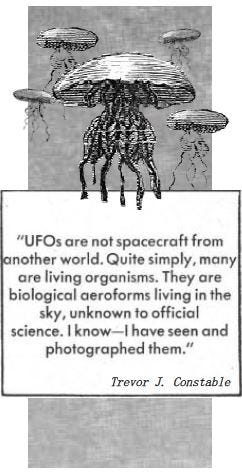

“Life may not be ‘piloting’ these ‘vehicles’ … Life IS the vehicle!” -Trevor J. Constable

While there are likely multiple meanings and messages embedded in Nope—including commentaries on the tenuous relationship between man and Nature, the personal cost of pursuing a legacy, and how to deal with everyday issues like confronting family drama—we came specifically for the promise of a classic flying saucer flick.

There’s a lot to like for those watching with a Fortean eye: The film’s strange occurrences take place on a desert ranch, not unlike that paranormal-powerhouse, Skinwalker Ranch. One of the main supporting characters is named “Angel” after those other strange aerial entities. The actors go off on a comedic rant about the government’s changing UFO language (they altered the name from UFO to UAP to hide the truth, because “no one knows what the f*** a UAP is!”). There’s even a recurring theme that will be familiar to students of the supernatural as the Haywood siblings try in vain to capture the phenomenon on camera. To be sure, Nope works in a fair share of fun asides for UFO fan boys and girls to pick up on.

Perhaps the biggest nod to ufology’s wide ranging field of ideas comes during the film’s ‘big reveal’ that the flying saucer plaguing the area isn’t a metallic craft from outer space—it’s a biological organism dwelling in the air.

The plot twist may sound original, but the concept is old hat to students familiar with ufology’s history.

The lineage of the film’s animalistic antagonist can be traced back to the works of OG anomaly author Charles Fort. He played with the notion that strange substances falling from the sky might be a byproduct of aerial creatures roaming the upper reaches of our atmosphere: “it seems no more incredible that up in the seemingly unoccupied sky there should be hosts of living things than that the seeming blank of the ocean should swarm with life,” (New Lands, 1925).

The idea that UFOs might be alive has taken different shapes over the decades. One of the originators was a Pennsylvania man by the name of John Bessor. As early as July 1947, Bessor felt compelled to inform the Air Force about the existence of atmospheric life-forms, alerting them to the potential that “these aerial objects represent a highly attenuated form of intelligent ‘animal’ life of extra-terrestrial origin.”

The USAF didn’t completely disregard the biological UFO theory—a Project Sign technical report from February, 1949 included space creatures as one possible explanation. Witnesses often recalled objects displaying life-like motions or maneuvers, and the government’s official documentation admitted that “the objects as described act more like animals than anything else.”

A USAF Project Sign technical report from 1949 considered space-animals as a solution to the UFO question.In the summer of 1957, author and UFO experimenter Trevor J. Constable accidentally “stumbled across these organisms,” when he captured evidence of unseen animals over our heads.

In order to catch these organic “aero-forms” on camera, he developed a method of “dark spectrum photography” using infrared film. His process revealed that our seemingly empty skies were crawling with large, amorphous objects. Invisible to the naked eye, they were occasionally perceptible when they became dense enough to manifest along the spectrum of human vision. Constable attributes a large portion of UFO reports to these misidentified air-amoeba. His first book, They Live in the Sky (1958), expounds on the nature of space “critters” with multiple pages of photographs showcasing strange entities traipsing across the atmosphere.

Constable’s opinions were shaped by the theories of esoteric researcher and Borderlands Science Research Foundation founder, Meade Layne. Layne contemplated the existence of quasi-living entities that subsisted in a mystical layer of “ether” enveloping our planet. Blending these ideas with the controversial science of Wilhelm Reich, Constable developed his own understanding of life-forms in the atmosphere.

The possibility of living-UFOs gained some traction, albeit marginally. At one point in the 1950s, well-known cryptozoologist Ivan T. Sanderson got in on the sky creature craze with a piece published for Fantastic Universe (UFO Friend or Foe?, 1957). In the article, he suggests that UFOs might be “as yet unsuspected Life-Forms, feeding on pure energy.” His subsequent book-length rumination on various aspects of the UFO mystery, Uninvited Visitors: A Biologist Looks at UFOs (1967), asked the question directly: “Could UFOs or UAO’s be Alive?”

Indeed, Sanderson gave the idea ample consideration, often wondering whether UFO observers were seeing “plain inanimate machines, or life-forms, such as animals or plants.” He pushed the issue further in a speech delivered to the 1967 Congress of Scientific UFOlogists. In front of a crowd of nuts-and-bolts saucer-enthusiasts he stated that the available evidence made a convincing case for an unpopular opinion: that UFOs “could be energy-eating animate objects.”

Sanderson’s musings were heavily influenced by the writings of a European aristocrat, medium, and spiritualist, Countess Zoe-Wassilko-Serecki. Among strong opinions on a diverse array of occult topics, she posited that UFOs might actually be “creatures from the stratosphere.” She suspected they were specially adapted to live in such an extreme environment, with the ability to sustain themselves on forms of raw energy. The countess thought that these organic aerial objects might be appearing more often because of their desire to feed on our planet’s increased electrical output.

One of Constable's critters is caught on infrared film hovering above power lines in Hollywood, California. Unlike the eating habits described by these early researchers, Nope’s airborne animal feasts on humans and horses—an unsettling possibility explored by UFO writer John Bessor in an article for Fate magazine in 1955 (Are the Saucers Space Animals?): “We shudder when we read of the many falls of flesh and blood from the sky in times past and wonder whether a species of ‘saucer’ is carnivorous, finding animals and humans a tasty dish.” His predatory interpretation of these airborne animals compliments Charles Fort’s conjecture that perhaps missing humans were being “fished for by aerial intruders.” Nope revisits these themes in vivid cinematic splendor, with one scene faithfully mimicking Bessor’s gory description of a space creature dumping its effluent.

We also see Nope’s organic flying saucer interfering with electrical systems, causing them to lose power or malfunction when it’s nearby. When dealing with a mechanical craft, this phenomenon is readily understood to be a result of the UFO’s powerful energy-field or possible jamming capabilities—but how is this side-effect accounted for when the flying object is a biological entity? Constable and crew have these bases covered. They propose that these atmospheric critters are “plasmic-beings,” akin to a form of high-voltage living-energy. A creature composed of such a substance would certainly wreak havoc on any electrical fields in its vicinity.

While the mainstream preferred to view UFOs as pieces of alien hardware, eventually flying saucer poster-boy Kenneth Arnold entertained the idea that they were alive. According to his 1962 article in Flying Saucers magazine, he’d abandoned the thought of interstellar technology patrolling the skies: “After some 14 years of extensive research, it is my conclusion that the so-called unidentified flying objects that have been seen in our atmosphere are not spaceships from another planet at all, but are groups and masses of living organisms.” His endorsement did little to attract adherents to the theory.

Maybe aero-biology advocates have a point—it would help explain how some UFOs are able to pull off dramatic maneuvers without crushing an on-board pilot. There are also plenty of anecdotal tales about interactions with bestial UFOs. Flying Saucers printed one such letter from a reader who had a run-in with a wounded aerial life-form near Battle Mountain, Nevada in its October 1959 issue:

“While walking about the top of this place we noticed something coming in for a landing. It was about eight feet across and was round and flat like a saucer … This next you won’t believe, and I don’t care, but it’s the truth. We walked up to the thing and it was some animal like we never saw before. It was hurt, and as it breathed the top would rise and fall making a half-foot hole all around it like a clam opening and closing. Then we saw a large, round shadow fall on us. We looked up and ran. Coming in was a much larger animal 30 feet across.”

In a 2010 piece for Fate magazine (Are UFOs Alive?), paranormal author and investigator Brad Steiger related a similar story shared with him by publisher Fay Clark. Clark claimed that he witnessed a UFO exhibiting animal-like behavior as he watched it “breathing” and “studying” his car. These descriptions are consistent with how Nope’s untamed sky critter acts—it’s shown stalking its victims and learning from its interactions—much like a hunter going after its prey.

Clark goes on to say that he watched as his object created an “artificial cloud” in an attempt to obscure itself from view. Using the same tactics, Nope’s saucer also manufactured its own stationary cloud as a form of camouflage. This ability allowed it to hide in plain sight for at least six months.

After his UFO experience, Fay Clark was convinced he’d seen an organic entity, not a vehicle: “I do not believe that we observed a craft made by beings from some other planet. I believe that we were watching a living creature, a form of life.”

Some “plasmic fauna” researchers suggest that they aren’t interstellar visitors—they’re a species native to Earth. This possibility is also hinted at in Nope. At times, the movie’s airborne organism behaves like an aggressive animal protecting its territory.

For the most part, theories about creatures living above the clouds, flew below the radar. Suggesting that UFOs were anything but physical craft was a hard sell to a 1950s-era ufology community enjoying a period of unprecedented technological advancement. Satellites and rockets were being sent into orbit with humans on board while science was unlocking the wonders of atomic energy—the notion that flying saucers were flying ET machines was too timely, too appealing. Semi-intelligent, energy-eating sky beasts were a tad too primitive.

While responses to the theory were decidedly mixed, ufologist Gray Barker describes how Trever Constable was made to feel like an outsider among the contactee-crowd for his views about space critters. A December 1958 piece for Flying Saucers magazine recaps his attendance at the contactee-oriented Giant Rock Space Convention where despite his own experiences communicating telepathically with space people, Constable’s ‘UFOs-are-animals’ pitch was labeled as “heresy.” It’s understandable that a group claiming to be in contact with the “space brothers” aboard flying saucers would take issue with the idea that mysterious aerial vehicles were really atmospheric organisms.

Barker wrestled with the thought of listing James’ work for sale in his own magazine after evaluating the blow-back he’d receive: “The ‘objective’ researchers who swore up and down that the saucers were coming from ether planets would be down on me; and the other camp, which believed that space people were the embodiment of sweetness and light, would also raise a fuss.” Yet even Barker conceded that Constable’s critter theory “was logical, even almost too painfully logical.”

It wasn’t just contactees who took umbrage with the idea—serious researchers rejected the premise as well. In a letter to the editor of Saucers, Space, and Science (Spring, 1964), ufologist Ricky Hilberg discredited Constable’s picture taking process, explaining that images of “critters” were merely the result of bad photography and “hogwash.”

Non-ufologists also weighed in on the topic. Science-fiction author C.M. Kornbluth called the aero-animal hypothesis “a charming piece of floss-candy” (Fantastic Universe, Dec., 1957). He challenged Fortean investigators to test their wild suppositions in the real world. If living-UFOs existed, then surely there was a way to bait one. So why weren’t any saucer-traps being erected? Revealing a distaste for the entire field, Kornbluth blasted the inaction of speculating spectators like Sanderson: “Think about it; believe in it. But do anything? No; that’s clean off the coordinates of Ufology.” (Here Kornbluth conveniently forgets the fact that Sanderson, an accomplished biologist, undertook multiple scientific expeditions across the globe in search of unknown species of life.)

Ultimately, the sentient nature of Nope’s UFO may seem unconventional to many movie-goers, but the plot is deeply rooted in a little-known chapter of ufological lore. The film’s success might change that obscurity. And who knows—perhaps one day we’ll discover that some crop circles are really “saucer nests” made by a species of space critters.

That's a great example.

We also came across the Japanese movie 'Dogora' which has a tentacled creature from space attacking from the sky.

There was also the Arthur Conan Doyle short story from 1913 called "The Horror of the Heights."