The Home Haunts Us

or "Why I Ignore the Strange Noises in My House." An analysis by the fearless Blake Collier

“The hole suggests an inability to enforce the order or territoriality of the body. It may operate independently of the will of its host—performing strange functions, allowing traffic in or out. The break is a threshold of momentous, and possibly dangerous, agency.” (1)

Imagine for a minute the lure of a quaint Queen Anne style cottage nestled in, what is now, the West Highland neighborhood of Denver, Colorado.

Now place yourself in the shoes of an individual whose health was already run roughshod and had no certain shelter at which to arrive home. It’s September and the immanence of another cold, blustery winter weighs heavy upon your body, meanwhile the last vestiges of self-preservation and survival rear their head when the house stands there empty, for now. We all know that breaking and entering carries a variety of unknowns and the risk factors are high, if caught. Yet this house is different. You have a history with this specific house. You have a previous relationship with its owners. Originally, you’d ventured here to ask for help, hoping they would have concern and take pity upon a former acquaintance. However, no one is there to inquire of, so you take the risk. Forgiveness can come later?

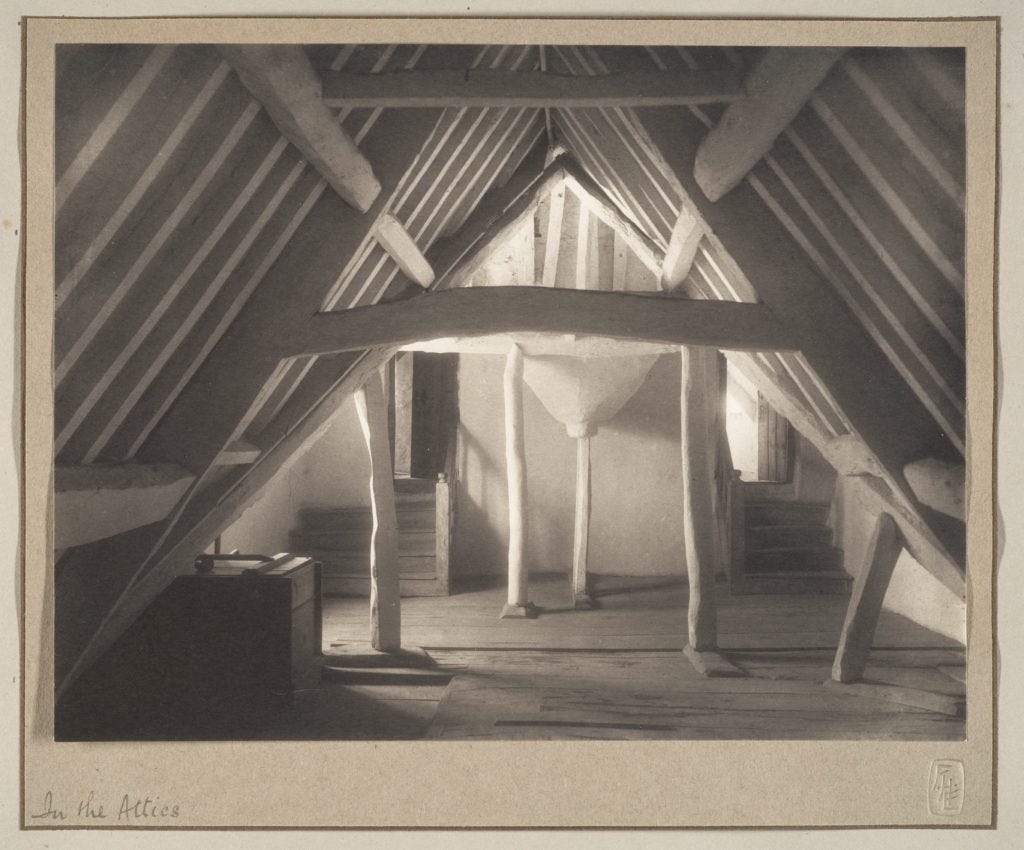

You enter from the outside, into the coziness of shelter. You eat of the food in their refrigerator and pantry. This had been the extent of your plan at this juncture when you see out of the corner of your eye a small trapdoor “only about 2 ½ times the size of a cigar-box lid, which led to a narrow attic cubbyhole.” (2) (This would have probably been around an 8”x15” hole in the ceiling if this author is to be believed and all the sources I found speak to its veracity.) At this point you decide to scrounge up some items from the residence, including food and a radio, and consolidate your gaunt, starved body up through this residential hole. There you stay for five to six weeks. You scurry down at night to get more food and items when you know the older gentleman who lives there is fast asleep. Until your luck runs out. You misjudge the gentleman’s nap for his departure from the house. This…this is when he discovers you standing in front of the open refrigerator. He runs for help. You bludgeon him to death, and you scuttle back to your hole. This is your new life.

This was the life of Theodore Edward Coneys—known as The Denver Spider-man, or Ghost-man depending on the paper you read—who was finally caught for the murder of Phil Peters in 1942; a man whom Coneys had played music with years prior in his youth.

“Modern buildings, like modern subjects, thus began to house unspeakable cavities…Those who work in design and construction are familiar with these obscure and recessive spaces, how they contradict the resolved bourgeois exterior. Simply put, they are a mess.” (3)

Attics and basements are not typically showcased within architecture of any period. Most of the time, they are practical. Basements are used for housing (and climatizing) wines, torturing enemies of the kingdom and providing protection against tornadoes, but they, now, and most assuredly their ascendant cousins, are used for storing stuff that we can’t quite offload (perhaps due to a generational psychological inheritance of accumulation as a means for upward mobility). These spaces are generally a means of concealment. This is probably why children have a natural disinclination to descend into the dim, dank interiority of their basements. They are not comforting. They are stark and seldom fully lit. They are a home for shadows and the entities that lie in wait.

For all their built intention for concealment, there is always a hole to these spaces—whether a door, manhole, or crumbling, rotting structure. There is always a liminal space between the inside and the outside. A threshold from there and to here. Modern buildings do not deal in the solidity of stone and handmade brick any longer. The building’s evolution has become symbolically (at the very least) more human. Like the interworking layers of human skin and the skeletal support that is hidden beneath, modern partitions are assemblies of metal and wood bones and often numerous layers of membrane that protect the structure from natural intrusion from the outside. Yet just as the human body has holes which give way to the symbiotic relationship between that which goes in and that which is expelled, the holes of the building imitate. These concealed spaces where stuff accrues or where plumbing and electrical wiring are hidden never fully allow for the full territoriality of “the home” with all its control, safety and familiarity in tow.

The externalizing of these spaces can be something as relatively common as water vomiting out from a broken pipe or an electrical short shooting its burning presence up the very spine of the structure. While these discharges from our man-made bodies can be off-putting and even dangerous, they do not garner the inherent terror of when these concealed spaces are penetrated, when something or someone that does not belong intrudes. This would be what is at play in the terror of a Coneys living, unknown, in the attic. Or a Daniel LaPlante who “was obsessed with fellow teen Tina Bowen” and found his way into the Massachusetts teen’s home “where he found a hiding place in a wall cavity next to the bathroom. He started taunting Tina and her family by emitting strange noises, drinking leftover milk and changing TV channels. One day, he took Tina, her sister, her father, and a friend hostage with a hatchet.” (4)

Coneys was no stranger to this kind behavior since he quite literally “holed” up in the Peters’ attic which was, according to several sources, a few sizes larger than a coffin. As stated on the now defunct site prisonmuseum.org, Coneys noted in his confession to police that he grew bolder in each of his nocturnal missions:

“Whenever I heard him downstairs, I kept real still. Then I got bolder and used to shadow him from room to room. It was sort of a game. It gave me a thrill. It was the first time in my life I'd ever had anyone at my mercy, but I didn't want to hurt him.” (5)

Scratches and knocks on the wall and footsteps up above us accompanied by strange noises that do not equate with the normal creaks and exhalations of our residential bodies tend to set our nerves on edge. If its origin cannot be found, they make our minds teeter into the realms of the poltergeists like those at Amityville and Enfield. However, at that point, is there, in fact, any metaphysical difference between a poltergeist and a boy hiding in a wall cavity; a man living in a cramped attic above us? This is the Schrödinger’s cat of reality. In the shroud of the unknown, both skeptical materialism and supernatural disembodiment are true and untrue. It is not until we cross the threshold of the hole—that vacuity of our proclaimed territory—that we can attain some semblance of knowledge.

“Whoever passes from one to the other finds himself physically and magico-religiously in a special situation for a certain length of time: he wavers between two worlds. It is this situation which I have designated a transition.” (6)

Arnold Van Gennep notes in his book The Rites of Passage that our modernized conception of ‘liminality’ breaks down into three separate phases: preliminal rites, liminal (or threshold) rites and postliminal rites. It is this middle series of rites that we are most infatuated, because it is harder to fully grasp what exactly is going on here; whereas the other two have grounding in a being that is theoretically before and then after. Gennep states that “[a] rite of spatial passage has become a rite of spiritual passage.” In this way, Coneys (and any of the other ‘phroggers’ as it is so cutely named now) by crossing the spatial threshold of the residence and then the attic door has enacted a rite of passage. He is becoming something else. He is becoming something other. He is becoming Peters’ shadow. He is becoming the once and future spiderman. Where he once wasted away in the cold, starving in his own poverty, he crossed the threshold into something that transcends rational description. He is man and haunt.

This is the fear that we all feel when we ponder the exigent holes in the structural bodies and membranes of our humble (or not-so humble) abodes. For deep down we all know that these holes can’t always remain incontinent. They will expel from their aperture darkness and with it the entities corporeal or incorporeal, both come flowing across the thresholds of our fragile human constructions.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.” (7)

Perhaps to riff on Blake here it seems that some of these metamorphoses—or rites of passage— falter into the negative. When in Coneys case he literally crosses thresholds, he not only begins to close the Infinite up through his limiting perceptions, but journeys toward becoming one with the space he inhabits. He becomes unto the concealment. He is the voided space in which he resides. As it so happens in many of these real-life cases, that void indelibly spills out and what each of these humans have become is no longer recognizable, just negative space longing to be re-housed again.

Maybe this is some strange explanation when navigating what we mean when we talk of ‘haunted houses’; for the term itself speaks nothing of the corporeality of the haunt, only how it chooses to cling to physical, built structures. How the haunt’s being is eternally becoming one with the wood and metal bones and the gypsum board and plaster and the paint and trim like layers of skin born again. Whatever is haunting these houses, whether human or ghost, they are striving to embody the buildings they have concealed themselves in so that they may taste a simulacrum of their closed-up Infinite.

BLAKE I. COLLIER grew up in the flatlands of the Texas Panhandle and now resides in the green country of Oklahoma with his wife and two boys. Reach him at: blakeiancollier@protonmail.com

Endnotes

1. Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing, Horror in Architecture (s.l: ORO, 2013), 122.

2. Carl Sifakis, The Encyclopedia of American Crime (New York: Smithmark, 1992), 565.

3. Comaroff & Ong, 129.

4. Elena Ferrarin, “Phrogging: Urban Legend or Real-Life Crime?,” A&E, May 17, 2023, https://www.aetv.com/real-crime/what-is-phrogging-and-is-it-real.

5. Juan Ignacio Blanco, “The Spider Man,” Theodore Edward Coneys | Murderpedia, the encyclopedia of murderers, accessed September 14, 2024, murderpedia.org/male.C/c/coneys-theodore.htm.

6. Arnold Van Gennep, Monika B. Vizedom, and Gabrielle L. Caffee, The Rites of Passage: A Classic Study of Cultural Celebrations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960), 18.

7. Blake, William, and Geoffrey Keynes. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), xxii.

Really enjoyed this article. When is the house a home or a haunt? If you're from across the pond, "Getting knocked up in the night" has a whole different meaning. Interesting fact, one of your sources, Carl Sifakis, The Encyclopedia of American Crime (New York: Smithmark, 1992), also wrote the book: Official Guide to UFO Sightings State by State Encounters (A drake Publication, Sterling Publishing, 1979)