Linda Godfrey hunted werewolves or, as she called them, dogmen. She wasn’t a superficial investigator. She didn’t hide behind her keyboard. She interviewed witnesses, researched historical precedents, and visited locations where sightings occurred. This approach gave her a unique insight into the bipedal canine phenomenon.

Her foray into cryptozoology began in 1991 with her coverage of a local legend known as the ‘Beast of Bray Road’—a wolf-like creature that reportedly moved about on its hind legs.

Like every good hunter, Godfrey analyzed the evidence for consistent patterns. She was interested in the specific geographic details of each sighting, noting the presence of certain “cultural artifacts tucked into the nearby landscape.” Anomalous bipeds often appeared near water—usually at night. They seemed to be attracted to sacred sites like burial mounds, crossroads, and cemeteries. This led Godfrey to wonder whether something spooky might be lingering in these environments, creating liminal places “where borders between reality and unreality seem to fuzz and fray” (Real Wolfmen, 2012).

The reports she compiled also described similar physical characteristics: a muscular build, pointy ears on the top of the head, long hair covering the body, snout, and a penchant for moving about on two feet. While they were prone to act aggressively, the creatures weren’t known to harm humans. Godfrey thought some of these behaviors (walking vertically, chasing witnesses) could be defense mechanisms meant to ward off anyone encroaching on their territory.

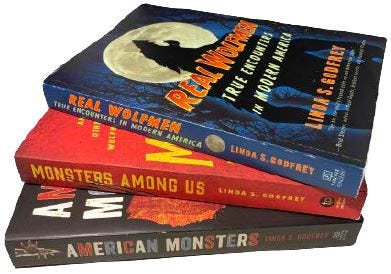

She rejected the idea that upright canine cryptids were werewolves in the traditional sense. She didn’t buy into Hollywood notions about the power of the full moon to bring about unnatural human transformations. Through multiple books and articles she entertained every aspect of the mythos—even fringe possibilities suggesting that dogmen were “holographic guardians created by sophisticated technology,” or “bio-engineered wolfmen designed by rogue or ‘black ops’ scientists to be ultimate warriors.” Since nothing about the strange lupine specimens was known for certain, everything was open to speculation.

Unlike Bigfoot, cryptid canines don’t leave much physical evidence behind. Godfrey relied on anecdotes and eyewitness testimony to extract details regarding her elusive prey. By keeping an open mind and treating the topic with respect, she found people were eager to share their encounters. She was careful to preserve the experiencer’s voice, and “tried hard not to ignore inconvenient evidence—pro or con”—no matter how strange it sounded. As a result, some of her tales had a tendency to stretch the limits of belief. But Godfrey’s gift was the ability to weave accounts together to highlight similarities and analyze potential explanations.

Linda kept a keen sense of humor despite her solemn subject matter. In American Monsters (2014), she recounted a story told by a Texas rancher who lost 26 chickens to an unknown attacker. Their bloodless carcasses hinted at a supernatural culprit à la the goat-sucking chupacabras, however there was little evidence that their fluids had been “sucked” out cleanly. More likely, the birds had their throats punctured and the flowing blood was then lapped up by the mysterious assailant. Riffing on the idea, Linda suggested a new name for this potential cryptid—instead of calling it a “goat sucker,” she dubbed it a “chicken licker.”

In 2012, Godfrey had her own run-in with a hairy biped (she suspected Bigfoot), and was transparent about the “philosophical problem” of admitting such an encounter. She worried “whether reporting [her] own personal experiences takes away from [her] objectivity as a reporter and researcher?” It’s one thing to act as a documentarian—disseminating other people’s wolfmen accounts keeps the phenomenon at arm’s length—but believing you saw something highly strange yourself can forever skew your neutrality and reputation. In the end, Linda stood in solidarity with the decades of witnesses represented in her books, allowing herself the latitude to tell her story as she experienced it.

Even after tracking the dogman legend for over 30 years, Godfrey never arrived at a concrete conclusion about the nature of unusual upright canines. She favored the idea that they were tangible creatures visiting us from a different plane of reality, but about the only thing she knew for certain about the phenomenon was that “people keep seeing them.”

Are dogmen beasts with human qualities? Or humans expressing their inner beasts? Linda Godfrey believed the former, writing in Real Wolfmen that “most are not one bit human.” She may have modestly refused the mantle, but she was the closest thing to a werewolf hunter this century has seen.

She recognized that humans show just as much interest in monsters as they do in us: “I, for one, would like to know what they’re up to.”

Hers was a mission of discovery, and a reminder that the world contains mysteries left to be revealed.

I’m heading to Bray Road soon to camp out at a hot spot she documented. I’ll let you know what I find, if anything!

Nice and timely retrospective on her invaluable contributions to folklore and high strangeness. The booklet for the new American Werewolves VHS I have coming out this week is dedicated to her, as a matter of fact. Her shadow looms over the rest of us.