As the United States’ Artemis Program makes strides toward putting humans back on the face of the Moon within the next four years, it’s time to revisit the history of bases, ruins, and artificial structures rumored to already exist on the lunar surface. NASA’s Ranger and Apollo, along with the Soviet's Luna and Zond Programs, are replete with anomalous images and videos that appear to show sprawling installations on the Moon. The subsequent satellites, telescopes, impactors, and orbiters captured further oddities across the landscape as accusations circulated blaming NASA of obscuring knowledge or altering evidence of these constructions.

In addition to visual irregularities, a handful of astronauts and whistle-blowers who took part in related missions tell stories of another presence already established by the time we touched down. As various military studies highlighting government interest in the topic became declassified over the years and more inexplicable pictures emerged, fringe theories and speculation about outposts on our Moon began to develop. It wasn’t long before the official understanding about the “lifeless” rock orbiting Earth slowly started to crater.

Men in the Moon

Before any of Earth's major powers adjusted their focus toward ways of building up the Moon, they devised ways to destroy it. Both the United States and the Soviet Union had similar aspirations when it came to exploding a nuclear bomb on the far side of the Moon. Project A119 was one such secret U.S. Air Force project in 1958 that addressed this objective. With the help of a budding young astrophysicist by the name of Carl Sagan, the study asserted that detonating a nuclear warhead on the Moon would be an impressive show of force for the United States - one that would visibly demonstrate their superiority to nations across the globe. The idea that our military was seriously considering a lunar nuclear assault would become a central component of later marginal theories involving the rubblization of an extraterrestrial Moon structure. While the study supposedly existed only on paper, it's worth noting that the lead of the project, Leonard Reiffel, later contributed at a high level on the Apollo Program as deputy director.

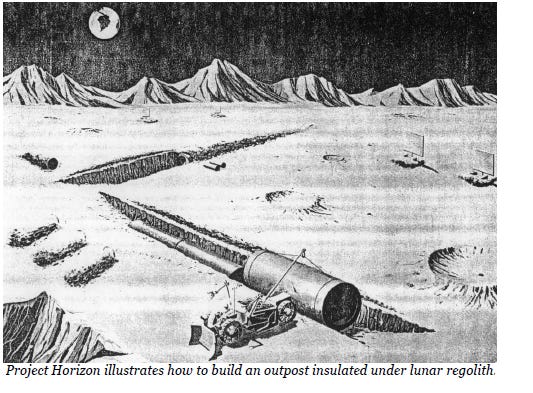

Control of the Moon would only be fully realized once a physical presence was permanently founded, or so was the thinking behind Project Horizon, an official U.S. Army proposal drafted in June of 1959. The study’s first two volumes consisted of over 400 pages detailing a method for reaching the Moon with enough materials and crew to begin creating a base of interconnected tubes underground. According to the Army, (a decade before Apollo 11 officially put a man on the moon) their “most challenging and perhaps the most urgent objective [was] that of establishing a manned lunar outpost on the moon.” With stakes that high, it's easy to imagine that such an undertaking could have been completed by the 1970s.

For those who might argue that the technology for such lunar endeavors wasn't available at that time, the Army's own report estimated that the first landings on the surface by any nation would take place by 1964 (they transpired in 1966), with astronauts in tow by 1965 (they tagged along in 1969). This reinforces the point that the military branches were not far off their estimations regarding the progression of space technologies. The U.S. suggested in the 1959 Horizon proposal that establishing a manned lunar outpost by the end of 1966 would require “no major breakthroughs” in technology, at one point plainly stating that “[t]he establishment of a lunar outpost is considered to be technically and economically feasible.”

Curiously, a sparsely circulated and hard to locate Volume 3 of the Army's Horizon proposal also detailed the weapons they recommended astronauts pack: pistols, claymore explosives, grenade launchers, and an atomic missile. This is an impressive arsenal to bring to an ‘uninhabited’ destination. However, a cache with that much fire power could conceivably do damage to an existing presence already on the lunar surface.

Not to be outdone by their military counterparts, the U.S. Air Force commissioned their own feasibility study in 1961, explaining how they would get to the Moon and back. The report included the creation of a multi-person Moon base to be constructed by 1968 under the surface. Their plan, blatantly named Lunar Expedition (Lunex), was outlined in a 198-page document that concluded “it is technically and economically feasible to build a manned lunar facility.”

The level of detailed consideration given to installing a settlement by these military branches is indicative of the degree of earnestness they placed on such a mission. Not only were there political, psychological, and national defense benefits to claiming lunar real estate, there were also potential resources, advantages in global communication, and an unparalleled edge in deep space travel to gain. Using the far side of the Moon as a launching station for further space exploration was among the top priorities of both proposals. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) documents from the period illustrate how a U.S. Moon terminal was considered serious business. In what appears to be an unsolicited bid by Aeronca Manufacturing Corporation to sell the agency on a program to weaponize space, Aeronca’s marketing team echoed the gravity that the U.S. government placed on the subject. Their aggressive sales pitch warned that winning the lunar base race “may well be the decisive factor which will affect the entire balance and the future history of earth.”

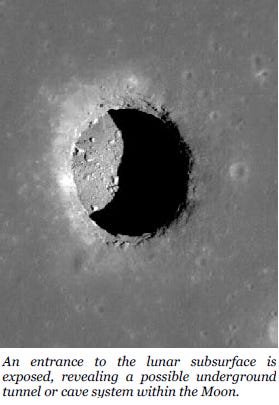

Most designs for a lunar station leveraged the existing topography of the Moon to the settlement’s advantage. Project Horizon's outpost sought protection from extreme temperature fluctuations and incoming meteorites by forming manned bases within holes and caves, or buried in the ground. Lunex also specifically put forth a “facility designed to be constructed under the lunar surface.” Indeed, many of the alleged Moon terminals seen in photographs appear to be built into the side of existing rock formations, craters, or alongside canyon walls. Correspondingly, some of the architecture heralded as artificial in photos looks as if it were covered with a layer of lunar soil after construction. This lunar dirt would serve as a natural form of insulation, which is consistent with the techniques suggested across various public and private proposals, implying that the possible complexes glimpsed in images are compatible with recommended building methods.

Further clues that the United States saw Moon bases as a priority come from Vice President Hubert Humphrey. His remarks on the Congressional Record in 1966 revealed his sincerity concerning the topic. Without fixing a specific timeline, he expressed his vision of “the exploration of the lunar surface, and possibly the establishment of one or more permanent bases there.”

Humphrey’s comments came amid Soviet plots involving the Moon and the creation of permanent basecamps. Their own N1 Program had an explicit goal in the early 1960s: “establishment of a lunar base.” As part of their mission, the long term installation known both as the DLB Lunar Base or Zvezda was planned from a series of connected pods protected under a layer of lunar regolith. This accomplishment would provide a headquarters from which to further explore the mysteries of space and solidify Soviet dominance in a new sphere of combat. Boris Chertok, Deputy Chief Designer of the Soviet Space Program during that time, wrote in his autobiography that the Russians could “gain prestigious ‘revenge’ by creating a permanent lunar base by the end of the 1970s.” He was personally convinced “it really would have been possible to achieve this.”

A 1962 issue of the Ministry of Defense’s official journal Military Thought (a publication the USSR deemed ‘Top Secret’) expounded upon what the Soviet’s knew at the time about America’s lunar ambitions. The author of the report was impressed by “the potentialities that unfold with the employment of lunar bases”. The Russians seemed convinced that their Cold War enemy had “[s]pecific projects … being worked out which propose the construction of various structures under the surface of the moon.”

In a classic showing of Cold War paranoia, the U.S. was speculating about the Red Army’s lunar aspirations in a similar manner. It was the CIA’s official estimation in a declassified 1965 document that a Soviet “lunar landing may be followed fairly rapidly by the establishment of a Soviet base on the moon.” Subsequent Russian Moon base concepts continued to sprout up throughout the 1970s with the revelation of the Lunar Expeditionary Complex (LEK) among others. These projects helped keep the idea of manned lunar structures alive in the public consciousness.

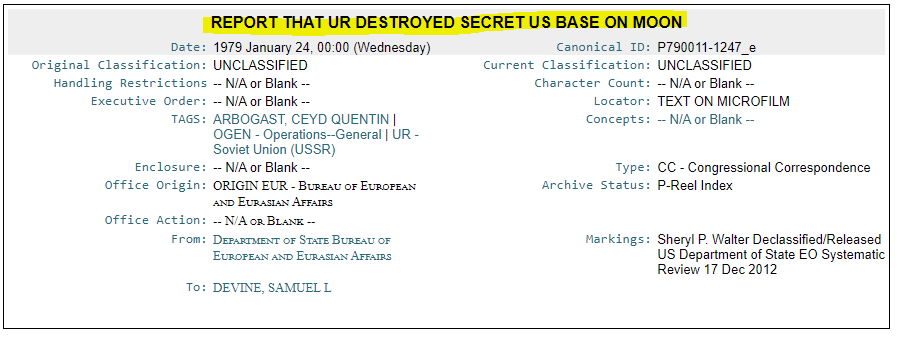

In a precursor to modern-day podcasts, Dr. Peter Beter (appointed by President John F. Kennedy as general counsel for the Export-Import Bank, 1961-1967) recorded and distributed his Audioletters (cassette tapes) containing monthly news reports and updates regarding Rockefeller sponsored secret government conspiracies and other unscrupulous plots to control the world. In one of his Audioletters from 1977, Dr. Beter revealed what he knew about the covert base on the Moon erected by the Rockefeller’s and their puppet regime. From a restricted military base in a remote area of the Indian Ocean (one of America’s largest overseas bases: Diego Garcia Island), this secret, classified space program successfully created the “perfect moon-port … from which secret missions to the moon have been launched during the building of the moon base.” The project culminated in the construction of a settlement within Copernicus Crater, a strategic location from which to install weapons that would solidify America’s (and by extension, the Rockefeller’s) total domination back on Earth. In what would become known as the Battle of the Harvest Moon, Beter goes on to tell how the tables were turned on the U.S., as the Soviet’s were able to demolish the U.S. lunar station in 1977 by employing a new weapon labeled as a “Neutron Particle Beam.”

Wikileaks unearthed an official document that adds credence to the conjectures by Dr. Beter and others about American and Soviet lunar bases. The Congressional Correspondence sent to Rep. Samuel Devine in 1979 from the Department of State’s Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs is short on substance. Its title, however, leaves little to the imagination: “REPORT THAT UR (SOVIETS) DESTROYED SECRET US BASE ON MOON.” The message does not give any further details about the context or contents, but the subject line suggests that if the United States did achieve a base on the Moon, the Soviets found a way to neutralize it.

NASA released a set of principles last year, known as the Artemis Accords, which define how the U.S. will approach the Moon, space, and the reclamation of its resources in the coming decades. Making it easier to mine and extract assets from outer space has become a very real goal of the Trump administration. Recently, Executive Order 13914 helped to clarify their stance about whether the U.S. and its private enterprises were subject to a 1979 “Moon Agreement,” which held that the Moon and its harvested resources should be regulated by an “international regime” in league with the United Nations. Section Two of the President’s executive order clears up any misconceptions about the country’s participation, stating explicitly: “The United States is not a party to the Moon Agreement.” These developments imply that our “dead” Moon in fact does contain valuable resources worth mining - knowledge that may have served as motivation for the creation of bases and mining operations in the past.

As the paper trail left behind beginning in the 1950s is collected and pieced together, it becomes easier to imagine the existence of human constructed lunar bases. Multiple official documents indisputably reveal that government desire was sizable; and the technical barriers they faced were decidedly limited more than 50 years ago when plans were first put forth. Yet regardless of how seriously human space agencies pursued their initiatives, many lunar anomaly researchers and fringe theorists see something decidedly more ancient and other-worldly in the perceived ruins and artifacts littered among the Moon’s craters.