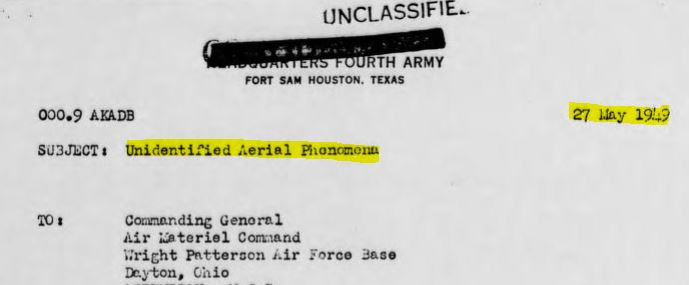

We’ll admit there’s an allure to using those other three letters to describe peculiar things seen in the sky. The term “UAP” (Unidentified Aerial Phenomena)— jargon used by the U.S. Air Force as early as 1949— is touted as the professional, polished version of its pop-culture predecessor, “UFO” (Unidentified Flying Object). The argument for its adoption is compelling, but before anyone renounces the original terminology, it’s important to take a closer look at the proposed changes to determine what’s really behind the word-smithing effort.

Critics complain that the letters ‘U-F-O’ are worn-out from carrying decades of “heavy cultural baggage.” Its affiliation with extraterrestrials has sullied its reputation. This class of acronym-abdicators are convinced that the “antiquated term” is so tarnished that it’s no longer in any condition to serve as the headliner for a topic locked in an eternal struggle for acceptance.

By contrast, ‘U-A-P’ has an official ring to it. It lends itself to a crisp, snappy pronunciation that leaps off the tongue—more militaristic and orderly than its boorish, sloppy-sounding counterpart. Finally, an abbreviation with some cachet! One that both professionals and interested hobbyists can use in front of friends and family without sounding like a ‘flying saucer nut.’ Discussing “aerial phenomena” at a dinner party elicits solemn nods and intellectual conjectures, not skeptical glances and sarcastic remarks.

Among those proposing a linguistic makeover is ufologist (uaplogist?) Mark Rainer, who presented the case for making UAP the de-facto descriptor in a 1999 article, “THE WAR OF THE WORDS: Revamping Operational Terminology for UFOs.” In his paper, he argues that the new phrase goes beyond just a necessary rebranding—it more accurately captures the qualities of a diverse array of reported sightings.

Here’s why he’s wrong.

We’ll cancel out the ‘U’ in both terms, since they stand for the same word (Unidentified), but we take issue with substituting the word ‘Flying’ with the word ‘Aerial.’ Rainer and his adherents ostensibly insist that their preferred lexicon does a better job of describing an item’s spatial location without implying that it has “self-propulsion, mechanisms, or an operator.” But we get it—“flying objects” lands a little too close to “flying saucers”—an association they are loath to make.

Unfortunately, their replacement also minimizes the core components included in centuries of classic UFO sightings (machine-like craft, occupants, purposeful movements). If not ‘flying,’ what else might the airborne anomalies that exhibit intelligent control be doing? Are they unidentified falling objects? There isn’t a better way to describe something that appears to maneuver and travel through airspace.

Furthermore, calling it a ‘Phenomenon’ as opposed to an ‘Object’ subtly diminishes the possibility of physicality. This might be the most nefarious byproduct of the proposal to rechristen UFOs. Instead of taking an agnostic opinion about the objective reality of strangeness in the sky, the word ‘Phenomenon’ implies a supernatural or ethereal nature.

For their part, UAPers harrumph about the bias inherent in the word ‘Object’—seeing it as a limiting factor that omits “ethereal possibilities” or other non-physical manifestations.

While we very well could be dealing with a paranormal enigma, the point isn’t settled at the moment. Supplanting the word ‘Object’ in favor of ‘Phenomenon’ simply prioritizes the metaphysical over the material in the audience’s mind, creating the same verbal conundrum that UAP-backers were trying to avoid.

Detractors quibble about using ‘Object’ to classify things like holographic projections, lasers, or plasmas. In Rainer’s opinion, if the ‘thing’ isn’t “solid,” or doesn’t have “physical mass,” then it isn’t an object.

While not ‘objects’ in the traditional sense, their status as a ‘thing’—a noun that people can wrap their heads around—is on par with the way we think about the light emitted from a light bulb. We can’t touch or feel it, but it’s very real and perceived objectively as an ‘item’ by the observer.

As more people turn to the digital world of NFTs and life in the metaverse, our understanding of what constitutes an ‘object’ has become more fluid. The dictionary’s definition even encompasses things considered intangible and immaterial—things of the ‘swamp gas’ variety. Merriam-Webster labels an “object” as “something mental or ...physical toward which thought, feeling, or action is directed.” This inclusive definition eliminates any reason to seek a replacement.

That the federal government has embraced the UAP lingo may be reason enough to remain wary. During a 2020 interview with The Black Vault, U.S. Navy spokesperson Joseph Gradisher explained why his branch of the armed forces chose to use “UAP” instead of other available phrases:

“It provides the basic descriptor for the sightings/observations of unauthorized/unidentified aircraft/objects that have been observed entering/ operating in the airspace of various military-controlled training ranges.”

What’s this talk about “aircraft/objects?” Even the military can’t stop themselves from describing the phenomenon as an object! Their response suggests that the official definition of a UAP is really just a sanitized way of calling something a UFO. Interestingly, the Defense Department’s latest attempt to fund a UFO group, the Airborne Object Identification and Management Synchronization Group—OMGUFOS!—reverses this trend, preferring to call them “Airborne Objects” instead of “Aerial Phenomenon.”

If you can convince a UAP-advocate to drop the thesaurus and come clean about their motivation, most will admit that they’re trying to hide from a legacy.

Rainer and his ilk insist that “UFO has become synonymous with other-worldly spacecraft” causing “confusion and controversy.” Therein lies the key to the nomenclature change. Deserters like Rainer charge that continued use of UFO parlance “sets up a narrow and inflexible framework for honest scientific research.”

Tell that to professor Avi Loeb, director of Harvard’s Astronomy department and head of The Galileo Project, a venture designed to search the skies “for physical objects… associated with extraterrestrial technological equipment.” Loeb hasn’t limited his language to just “UAP” in order to secure credibility—the astrophysicist often uses the phrase “UFOs” when promoting his venture in the media.

In their rush to abandon ship, the UAP-brigade foolishly believes that the “cultural connotations of UFO” outweigh any “cultural staying power.”

A cowardly “fear of ridicule” and a disdain for the term’s reputation doesn’t justify its redefinition. What it needs is rehab, not a rewrite.

Besides, any alternative verbiage will be saddled with the same character issues as its forerunner. While UFOs take all of the flak for harboring an “association with aliens,” UAP evangelists have seemingly failed to notice that their rewording is haunted by the ghost of its ancestor—“a prisoner of this same past.” (Smithsonian Magazine, “UFOs, UAPs—Whatever We Call Them”)

Confusingly, Rainer’s paper reveals an inconsistency that can’t be ignored. He supports keeping the letters ‘u-f-o’ around in lowercase form to serve as a catch-all for “Fortean” encounters displaying elements of high strangeness. This proposition further dilutes the potential objective reality of anything labeled a “UFO.” To make matters worse, Rainer suggests pronouncing it “you foe”—hardly an endearing nickname.

It appears he doesn’t mind if the stigma associated with those three letters is applied to cases he deems paranormal.

Is “UFO” perfect? No. Is it better than “UAP”? Yes. When it comes to defining unknown things seen in the sky, terminology is extremely important. Selecting words to summarize that which we don’t fully understand is a challenging assignment. Reducing odd visuals in the sky to a mere three words is bound to create an oversimplification. Knowing this, it’s fair to call the vernacular’s clarity into question.

The problem with “UAP” is that it eschews the possibility of hardware in favor of an event detected by the senses. It undermines the impression of a physical object. It surrenders a perfectly good acronym, gives up undeserved ground to the skeptics and non-believers, and validates decades of ridicule directed at UFOs.

But indeed, some of these "objects" might not conform to our understanding of molecular physicality, which is why "UAP" is not totally unhelpful.

Thanks. As you note, government sanction is reason enough to avoid its use. Once the semantics are out of the way we can spend more time on the real detective work.