For a self-styled “legit scientist,” Paul Sutter likes to speak in hyperbole. “To put it bluntly,” the PhD physicist opined in a recent article for Space.com, “we know more about the curvature of the Earth than almost any other topic in the realm of physical science.” Putting aside the questionable accuracy of this statement, one would think that his piece, “How to debate a flat-Earther,” would be full of air-tight evidence proving a globe-shaped Earth. Instead, his article does a poor job of living up to its title.

The author begins by asking a question that makes it sound like he’s exhausted with the prospect of a debate before one even begins: “So, why do people believe this, and is it even worth getting into a debate over?” (We must assume his answer is “yes,” or he wouldn’t have written his article.) Sutter’s inquiry drips with the underlying suggestion that it’s a waste of time to attempt to reason with a person who doesn’t think that we live on a sphere. This is a classic tactic used to squelch dissenting opinions - by labeling them too crazy to entertain, the conversations are extinguished.

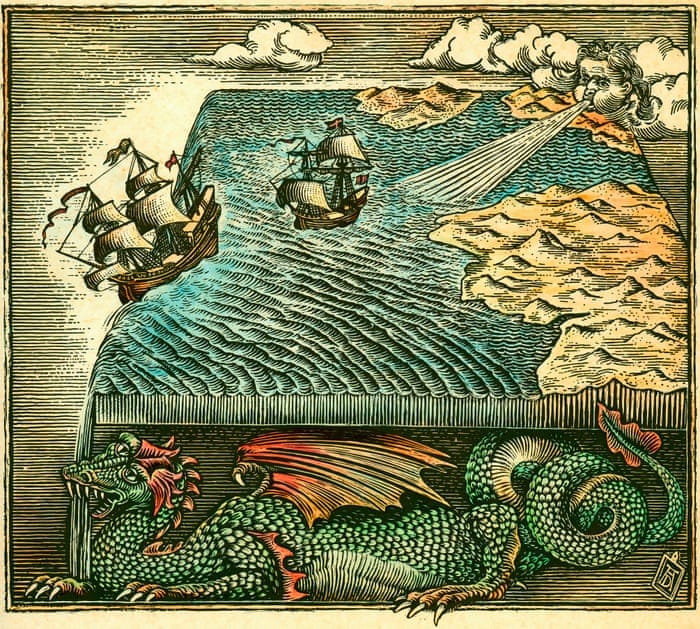

From there, Sutter transitions into a profound explanation as to why ancient people thought the Earth was flat. As he sees it, “simply, they didn’t know any better.” This statement, provided without example, flies in the face of what historians teach about early cultures’ understanding of complex astronomy. For example, the ancient Mayans, well-known for their accurate observations and measurements of the night sky, believed in a flat-Earth. In addition, the ancient Babylonians and Egyptians, regarded as highly knowledgeable about the movements of the planets and stars, also held that the Earth was an enclosed plane.

After his brief history lesson, Sutter’s article goes into some of the scientific evidence that proves the curvature of the Earth. He starts with a discussion of the horizon, reminding readers that, “as objects recede from you, they begin to look smaller and slowly disappear in a very unique way: first their bottoms become hidden, and then their tops. If you’ve ever watched a ship on the horizon, you’ve seen this for yourself.” The globe-Earth model asserts that objects far away on the horizon should “sink” below view at a certain distance due to the Earth’s curve. But what about the contrary evidence? Dr. Sutter fails to directly address or acknowledge the wealth of videos taken with telescopic zoom lenses that appear to show ships on the horizon that should no longer be visible based on their distance from the observer. These images can be hard to explain away and are often upheld by flat-Earth proponents as strong proof that our planet isn’t a ball. Yet Sutter’s article provides no cover for ball-Eathers looking to hide behind a strong scientific rebuke of these visual curiosities.

Sutter’s next proof touches on evidence found in the heavens, noting how different stars are visible in the northern hemisphere than the southern. The “legit” scientist posits this as more confirmation of our spherical planet: “...as you travel south, approaching the equator, Polaris sinks lower and lower toward the horizon. Once you’ve crossed that boundary, you can’t see it at all — it’s blocked by the curve of the Earth in that direction.” Admittedly, the star charts and maps put forth in the flat-Earth model fail to account for all of the nuances involving the night sky. However, Sutter’s constellation contention is countered easily enough by one of the original flat-Earth advocates, Samuel Rowbotham (who wrote under the pseudonym “Parallax”). In his 1865 book, Zetetic Astronomy: Earth Not a Globe, he confronts Sutter’s explanation head-on:

“Another phenomenon supposed to prove rotundity, is thought to be the fact that Polaris, or the north polar star, sinks to the horizon as the traveller approaches the equator, on passing which it becomes invisible.”

He denies that this is confirmation of a ball-shaped planet:

“It is an ordinary effect of perspective for an object to appear lower and lower as the observer goes farther and farther away from it... until, at a certain point, the line of sight to the object, and the apparently uprising surface of the earth upon or over which it stands, will converge to the angle which constitutes the "vanishing point" or the horizon; beyond which it will be invisible.”

He then applies this logic to explain why the north star deceivingly appears to drop below the Earth’s curve:

“This lowering of the pole star as we recede southwards; and the rising of the stars in the south as we approach them, is the necessary result of the everywhere visible law of perspective operating between the eye-line of the observer, the object observed, and the plane surface upon which he stands; and has no connection with or relation whatever to the supposed rotundity of the earth.”

While Rowbotham may have some holes in his application of this principle, you won’t find them exposed in Sutter’s article. Once again, his debate team finds itself without the necessary ammo to return fire on this common flat-Earth counterpoint.

The author does provide one proof that has proven to be unassailable by flat-Earthers: a lunar eclipse. During a lunar eclipse, the Earth moves between the Sun and blocks its light from shining on the Moon. If our planet were not a globe, able to interject itself in between two other globes in space, then the eclipsing effect of the Moon would be hard to explain. The flat-Earth model has some theories that attempt to account for this occurrence (most notably the supposition that there is an enormous, shadowy object orbiting the Sun that regularly blocks solar rays from reaching the Moon), but none are overly convincing.

Near the end of Sutter’s piece he noticeably runs out of steam, lazily proclaiming that “all of the other planets ever discovered also appear round, because that’s how gravity likes things.” He does not explain why gravity likes things this shape, or how it acts upon those things to make them round, or why humans and other objects are spared from this rounding effect of gravity. His argument amounts to: “because, gravity.” He then goes on to employ a truly baffling bit of “If/Then” logic. Even after multiple readings, it’s entirely unclear what point Sutter is attempting to make here:

“If you use gravity to, say, trust your GPS to give you accurate positions and calculate trajectories, then that same force will form material the size of the Earth into a ball.”

Huh? How the author gets from gravity, to GPS coordinates, to a proof for a round Earth is a mystery.

To round out his article, the astrophysicist abandons the debate altogether, and reveals that a conversation with a flat-Earth advocate isn’t even, “about the actual evidence or the scientific process.” This is fortunate, since his article does not provide much in the way of either. Instead, he explains that someone’s distrust of the ball-Earth model comes from, well, a “lack of trust.” Sutter goes on to lament this misguided lack of trust, especially when it’s aimed at, “elite representatives of that society, which includes… scientists like me.”

After ignoring all of the empirical evidence touted by flat-Earthers and reducing their arguments to nothing more than an unhealthy skepticism of the “elite” Sutter’s closing paragraph contains an ironic line. It appropriately sums up the “legit scientist’s” approach to the entire debate: “If you find yourself talking to a flat Earther, skip the evidence and arguments, and ask yourself how you can build trust.”

Seems legit.